Burkina Faso: Arming Civilians At The Cost Of Social Cohesion?

What’s new? Since taking power in Burkina Faso in September 2022, President Ibrahim Traoré has begun arming tens of thousands of civilians, known as the Homeland Defence Volunteers (VDPs). He has thus considerably stepped up the use of auxiliary corps created in 2020 to reinforce the army’s campaign against jihadist forces.

Why does it matter? The use of VDPs is a double-edged sword. They help defend national territory from jihadist groups by strengthening counter-insurgency operations. Yet, due to inadequate training and supervision by the armed forces, these volunteers suffer heavy casualties. Civilians are increasingly caught in the crossfire of their battles with jihadists.

What should be done? The authorities should recruit fewer VDPs and continue integrating those already enlisted into the regular armed forces under certain conditions. They should enhance the VDPs’ training, supervision and representativeness. They should sanction any proven abusers and improve relations with communities excluded from recruitment. External partners could support these endeavours.

Executive Summary

The Homeland Defence Volunteers (Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie, or VDPs) are a key instrument of the authorities’ counter-insurgency strategy in Burkina Faso. President Ibrahim Traoré has harnessed these armed civilians in a sort of patriotic mobilisation against jihadists, compensating for the armed forces’ limitations in strength and geographic reach. But the VDPs, who are often placed on the front lines with little training, suffer significant casualties. Some, through their actions, are even fuelling insecurity and undermining social cohesion. Observers accuse them of targeting civilians, particularly Fulani, and getting away with the crimes. Moreover, their presence within towns and villages exposes civilians to jihadist reprisals. To contain these risks, the Burkinabé authorities should slow recruitment of VDPs and make better use of the regular armed forces. They should also strengthen control mechanisms, so as to punish any proven offences, and improve their relations with communities excluded from recruitment.

In January 2020, President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré created the VDPs to fight jihadist groups, placing them under the defence ministry’s authority. Prior to this decision, groups of armed civilians known as Koglweogo (“guardians of the bush” in Mooré, the country’s main language) were already battling bandits in many regions. The first such self-defence groups appeared in 2013 as a result of local grassroots initiatives, coinciding with the end of President Blaise Compaoré’s regime – a period marred by heightened insecurity. From 2017 onward, the Koglweogo found themselves clashing with the jihadists who had emerged in Burkina Faso. Overwhelmed by the jihadists’ strength, Kaboré turned the Koglweogo into an auxiliary corps. These units had several shortcomings, however, as they never got the support the authorities promised. Many of them disbanded in 2021 and 2022. The regime of Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Damiba, which came to power with a coup in January 2022, did not fundamentally change this situation.

When, in turn, President Traoré rose to power in September 2022 following a second coup, he announced the recruitment of 50,000 additional VDPs to reclaim control of national territory. This initiative, which was partly financed by a new Patriotic Support Fund open to contributions from the public, has been very popular thus far. While VDPs are being deployed nationwide, they remain concentrated in urban areas. Their gradual expansion into rural zones faces significant hurdles, as the jihadists are strongest in the countryside. An important military asset, the VDPs continue to take heavy casualties and often criticise the army for its inadequate support. For now, their growing discontent is directed more at the armed forces than at Traoré, who still commands broad support among their ranks.

Jihadists are targeting villages where VDPs were recruited, causing many civilian casualties.

Although these tens of thousands of proxy troops have been mobilised to address insecurity, their actions paradoxically contribute to escalating violence through the alleged crimes that some of them commit against civilians, sparking retaliatory cycles among armed factions. VDP recruitment has largely taken place to the detriment of Fulani communities, whom the authorities and the auxiliaries often suspect of collusion with jihadists. Amid this distrust, some VDPs misuse their authority to settle local scores, frequently centred around land issues. As the VDPs deploy more widely across the country, violence against civilians is also expanding, affecting communities that were previously safe. A number of abuses have been investigated and legal proceedings brought against some VDPs. These measures remain limited, however, particularly with regard to alleged mass violence. At the same time, jihadists are targeting villages where VDPs were recruited, causing many civilian casualties.

Many of Burkina Faso’s Western partners have suspended cooperation with Ouagadougou since the second coup or, at least, shown reluctance to launch new projects. They find themselves in a complex predicament. On one hand, they are perplexed by the regime’s decision to rely so heavily on the VDPs. Some partners refuse on principle to support arming civilians, while others baulk at the practical problems of recruiting such volunteers. As a result, they cannot meet the new regime’s demand to arm tens of thousands of VDPs. On the other hand, these same partners have been prioritising investment in security initiatives for several years. They are hesitant to abruptly stall their efforts in this area and risk sacrificing the returns on this investment. They also fear that, if the new authorities’ security funding demands are not met, they will turn to Russia, as happened in Mali. Precisely that scenario has been gradually taking shape since the Russia-Africa Summit in July.

In 2020, Crisis Group voiced concerns that the introduction of VDPs would prove a double-edged sword – fears that are now being confirmed. Yet now that the authorities have placed VDPs at the heart of their security plan, they cannot instantly backtrack without the risk of undermining security. In addition, the VDPs are an important support base for President Traoré.

Without abandoning this strategy, the authorities can nevertheless take steps to mitigate its negative effects. They should slow recruitment of VDPs and keep integrating those already enlisted into the army under certain conditions, while strengthening mechanisms for monitoring these proxy troops in the army itself, which is frequently accused of violence against civilians. The authorities should also create community-based control mechanisms provided for in legislation to stem the risk of abuses that may be committed by VDPs. Lastly, they should seek to limit the repercussions of this violence on local social cohesion and encourage dialogue with communities that have hitherto been de facto excluded from the VDPs.

For their part, the country’s principally Western partners cannot contribute to arming or even training VDPs. They can, however, offer their support in introducing mechanisms to better control the actions of VDPs and curtail potential abuses. More broadly, they should deprioritise security investments when such projects are now difficult to reconcile with the approach taken by the new authorities. In particular, the European Union should continue to seek to convince Burkinabé leaders that its support in other areas like social cohesion and humanitarian aid is essential and should shift its own efforts in this direction as a matter of priority. The United States, which still holds influence in the country, could head an informal coalition of partners to engage in dialogue with the authorities and encourage them to ensure that the VDPs become a solution rather than remaining part of the problem.

I.Introduction

Since late 2015, Burkina Faso has seen a steady rise in attacks by two jihadist groups, the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) and Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel). 1 Confined initially to the provinces of Soum (where JNIM first appeared) and Oudalan (where IS Sahel emerged), both on the northern border with Mali, the violence has now spread to almost the entire country. JNIM is active or present in eleven of the country’s thirteen regions. 2 Only the Plateau-Central region has been spared, as three attacks took place in the capital Ouagadougou (Centre region) in the years between 2016 and 2018. 3 IS Sahel, meanwhile, is operating across the Sahel region, particularly in Oudalan.

These insurgencies have left thousands dead and displaced around two million Burkinabé within the country. They also caused two coups in 2022. On 24 January of that year, following a particularly deadly attack on gendarmes in Inata in late 2021, a group of officers led by Colonel Paul-Henri Sandoago Damiba ousted President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré. Kaboré had been voted in as president in 2015 and re-elected in 2020. Damiba was himself overthrown on 30 September 2022 by Captain Ibrahim Traoré, following an attack on a military convoy that killed 37 soldiers and dozens of civilians. 4

President Traoré has tried hard to recapture the parts of the country that have fallen into the hands of jihadists.

Like Kaboré and Damiba, President Traoré has tried hard to recapture the parts of the country that have fallen into the hands of jihadists. In pursuit of this goal, he has gone further than his predecessors in recruiting, arming and deploying Homeland Defence Volunteers (Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie, or VDPs). Created by Kaboré in 2020, VDPs are civilians recruited by the armed forces to form an “auxiliary corps”. 5 Traoré considered that “increasing troop numbers was essential” and saw the mass recruitment of civilians to support the army as the best solution. 6 In addition to the VDPs, Burkina Faso has other self-defence groups such as the Dozo (a brotherhood of some 5,000 traditional hunters in the west) and the Koglweogo.

The VDPs are now at the heart of Burkina Faso’s security strategy and have helped regular forces achieve several victories over armed groups. They have not yet restored peace, however, and have even spawned new kinds of instability in many regions. Although their sheer numbers, dedication and local knowledge have benefited the armed forces, they have also fuelled communal tensions and exposed civilians to jihadist reprisals. The VDPs – tens of thousands of civilians armed with military-grade weapons – are a double-edged sword, but the authorities are unable and unwilling to reverse their mobilisation. This report offers recommendations for countering their negative impact.

The analysis is based on fieldwork conducted in August 2022 and March 2023 in Ouagadougou and other regions affected by insurgencies. The dozens of interviewees include residents of these regions, state officials, military officers and civil society actors. Several additional interviews with Burkinabé and international actors were conducted remotely between February and November 2023.

II.VDPs: Armed Civilians on the Front Lines in Counter-insurgency Fighting

A.The First Wave of VDPs (2020-2022): A Weak Start

On 21 January 2020, after a year of intense jihadist violence, the National Assembly unanimously approved a government bill to create the VDPs as an “auxiliary corps” to be trained, equipped and placed under the defence ministry’s authority. 7 The Assembly was ratifying a decision that President Kaboré had made two months earlier, after 38 civilians were killed in a JNIM ambush in the East region. 8 That jihadist attack sent shock waves across the country; it was the deadliest assault since armed insurgencies began in late 2015. Kaboré responded by calling for “the general mobilisation of the nation’s sons and daughters to fight terrorism”. 9

The authorities also created the VDPs in an effort to manage self-defence groups that had existed since 2013, before the first jihadist attack. In many regions of the country, villages had formed the Koglweogo group to stem the growing insecurity that had gripped the country as Blaise Compaoré’s regime weakened and eventually fell in October 2014. 10 The Koglweogo helped improve security in rural areas and significantly reduced banditry. 11 Since 2017, as jihadist groups extended their reach from the Sahel region to the North and Centre-North of the country, overwhelming the Burkinabé armed forces, the Koglweogo joined the fight to ward off this new threat. 12

The Koglweogo began as a highly decentralised, local security initiative but eventually gained support from central authorities. In 2019, several members of President Kaboré’s ruling party, the People’s Movement for Progress, began supplying weapons to the Koglweogo from the Loroum and Boulsa provinces, likely with the support of the Plateau-Central’s traditional authorities. 13 These leaders considered arming civilians a way to combat jihadist expansion in Burkina. Inspired by the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs) created by Captain Thomas Sankara, the country’s president from 1983 to 1987, they hoped the Koglweogo would draw legitimacy from association with this highly respected figure. 14 A comparison with the CDRs is misleading, however, as these committees never had to confront enemies with military-grade weapons. Another difference is that the Koglweogo have never had a defined ideology, unlike the CDRs.

The VDPs soon ran into operational difficulties, mainly due to a lack of material resources, a problem that persists to this day (see Section II.D below). More generally, the first wave often operated outside their remit as VDPs, assigned to protect the interests of their “village or local area”, in practice went on to cover wider ranges, sometimes entire provinces. For example, Ladji Yoro, leader of a VDP group in northern Burkina, operated in the whole of Loroum province. 15 Another problem was identifying VDPs – who sometimes were not even officially registered – when mixed with untrained civilians. 16

The VDPs quickly found themselves on the front line of counter-insurgency battles, even though their activities were legally limited to self-defence.

More importantly, the VDPs quickly found themselves on the front line of counter-insurgency battles, even though their activities were legally limited to self-defence. 17 The army, reeling from a series of heavy losses, tended to stay in its barracks, leaving the VDPs to fight the jihadists on their own. 18 To make matters worse, a few months after the creation of the VDPs, the state signed an agreement (known as “Djibo agreement”) with JNIM to stop the fighting between the armed forces and this jihadist group between October 2020 and March 2021. 19 This pact excluded the VDPs, who then became the main target of the JNIM fighters. 20

A series of defeats and casualties weakened the especially vulnerable VDPs in their strongholds of Sollé (Loroum), Gorgadji (Seno), Arbinda and Kelbo (Soum), Bourzanga (Bam) and Tanwalbougou (Gourma). The VDPs, feeling abandoned, came to bitterly resent the state and the armed forces. 21 Many of them posted insults on social networks. 22

Between 2021 and 2022, this situation compelled many VDPs to lay down their arms and often to leave their home areas. These defections were mostly individual rather than collective decisions. In the North Central region, for example, dozens of VDPs put down their weapons in Nagbingou (Namentenga) and Bourzanga (Bam), fleeing to Ouagadougou or to Côte d’Ivoire. 23 In 2021, jihadist pressure in the North region forced the VDPs, in a strong position a year earlier, to retreat to the point of withdrawing from the fighting altogether until Captain Traoré came to power. 24 This pressure prompted some VDPs, and local communities in general, to negotiate the terms of their withdrawal with the JNIM. 25 This withdrawal generally went smoothly, although sometimes the VDPs lost or surrendered their weapons. 26

President Damiba’s short-lived regime, the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR), was ambivalent about the VDPs. The regime was quick to express its mistrust of these groups and accuse them of abuses. Yet the delicate security situation compelled it to try better managing these groups rather than taking steps to get rid of them. To this end, Damiba set up the Brigade of Homeland Vigilance and Defence in June 2022, attached to the National Theatre Operations Command, created in February that same year to coordinate all the anti-terrorist operations in the country. While seeking to bring them under control, the government tried to expand the VDPs’ presence. In August 2022, they announced their plan to set up VDPs in every district of Burkina. 27

In the event, neither the lengthy process of enhancing management nor the recruitment drive came to fruition, with the latter project encountering difficulties when some communities refused to set up VDPs. All hope of carrying out these plans was dashed when President Damiba was overthrown just a few months after these announcements.

B.The Second Wave of the VDPs: Actors of an “Armed Nation”

Shortly after coming to power on 30 September 2022 as the leader of the second Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration, or MPSR 2, President Traoré made “liberating the country” his top priority. To a much greater extent than his predecessors, he placed the VDPs at the centre of his anti-jihadist strategy. 28

Traoré considers VDPs crucial in counter-insurgency operations in which ground control is vital and merely mobilising the army does not suffice. 29 The VDPs have repeatedly repelled jihadist attacks and even ambushed jihadist fighters as in Arbinda (Soum), Gorgadji (Seno), Piéla (Gnagna) and, in June 2023, Falagountou (Seno). 30

For Traoré, the use of VDPs makes up for the failures of soldiers and the lack of commitment of some army units, riven by infighting exacerbated by the 2022 coups. 31 Thus, having lost the privileged status it enjoyed under Kaboré, the gendarmerie is now less active in counter-terrorism efforts. 32 Traoré, trying to regain control of the gendarmerie after arresting or replacing various units appointed by the previous regime, has started to rely more on the police. Since coming to power, he has mobilised the police in the counter-terrorism fight by deploying two elite units known as the Groupements des unités mobiles d’intervention, or GUMI. 33

[The VDP] nationwide presence means that they can supply intelligence and come to the government’s aid.

The head of state and his inner circle are facing tensions within the armed forces that could threaten the administration’s stability. 34 The VDPs could help consolidate the regime if it finds itself under duress: their nationwide presence means that they can supply intelligence and come to the government’s aid. Although the VDPs have not yet been used in this capacity, the regime has already mobilised its supporters in Ouagadougou following rumours of a coup against Traoré in September 2023. 35

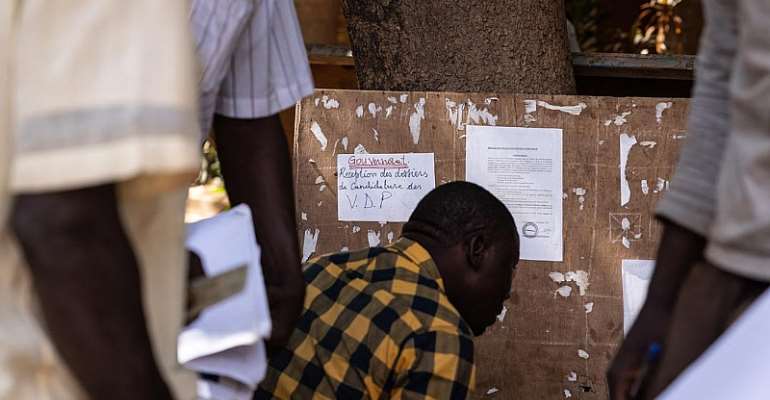

Therefore, on 24 October 2022, the MPSR 2 government announced the recruitment of 50,000 VDPs, double the number of soldiers in the army. People in Burkina broadly welcomed this mass recruitment drive, as a growing section of the population wants to help tackle the country’s rampant insecurity. The government reported that it had received 90,000 applications by November. 36 Encouraged by this enthusiastic response, the following May Prime Minister Apollinaire Joachim Kyélèm raised the recruitment target to more than 100,000 VDPs. 37 Exact figures are hard to come by, but it is likely that 30,000 to 60,000 VDPs had been recruited and mobilised by the end of September 2023, according to the authorities. 38 The vast majority of these VDPs are men, although women have also been recruited and deployed to the front lines.

Recruitment has been a gradual process. Candidates have to apply individually, which takes time; and the authorities want to avoid overwhelming the nation’s capacity to train and integrate the volunteers. Arming thousands of newly recruited civilians is resource-intensive. 39 In March 2023, a senior official described the process as being “adapted to the logistical constraints of the authorities”. 40

The 50,000 new VDPs are divided into two new categories: national and local VDPs (with the target of recruiting 15,000 and 35,000 members, respectively, according to official figures). 41 The former are tasked with fighting alongside the armed forces throughout the country, while the latter are responsible for security in their “commune”, giving them a broader remit than the first wave of VDPs which operated only at the village level. 42 National VDPs report to the defence minister and receive training in three army camps. 43 Local VDPs, under the authority of the Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralisation and Security, are trained at police headquarters or the gendarmerie barracks closest to their home community. 44

Officially, the national VDPs “are practically soldiers”, according to a Burkinabé official interviewed by Crisis Group. 45 Embedded in army units, they receive the same equipment as the troops and follow the orders of the army as they carry out joint attacks as part of “mixed battalions”. 46 In time, many national VDPs are expected to join the army, as happened during a recent recruitment drive of 5,000 soldiers that sought to enlist “young [national] VDPs”, according to Defence Ministry statements on 23 February 2023. 47

Local VDPs receive defensive assignments to improve security in their home communities. 48 Their main task is to carry out patrols to prevent jihadists from expanding or returning to reclaimed rural locations. Additionally, they are supposed to protect critical infrastructure (such as bridges, schools, electrical antennas, water and electricity plants), although in practice they only perform this function in some areas. 49

The goal is to deploy 100 VDPs in each of the country’s 351 districts. 50 VDPs are now operating in several districts for the first time, particularly in areas that have become vulnerable once again to jihadist violence: provinces in the Boucle du Mouhoun, Hauts-Bassins, Cascades and South-West regions. Similar developments have taken place in the Centre-West and Centre-East regions, where residents have largely resisted the deployment of Koglweogo groups. 51

People living in the capital are aware that jihadism is no longer confined to remote parts of the country but is coming dangerously close to Ouagadougou.

The mass recruitment of VDPs in regions where they were previously scarce, in addition to being broadly welcomed by the public, has happened for three main reasons. First, locals in these areas are increasingly feeling the need to resist the growing jihadist threat, with newly displaced people and victims of these jihadist groups or their relatives (men and women) expressing readiness to join the VDPs. Secondly, people living in the capital (who account for most new recruits) are aware that jihadism is no longer confined to remote parts of the country but is coming dangerously close to Ouagadougou. Finally, the Dozo and some Koglweogo groups who refused to join the VDPs during the first wave of recruitment now fear being shunted aside by the VDP recruits, especially if these volunteers belong to rival communities. 52 Many members of these two groups eventually decided to join the VDPs.

According to the authorities, the national and local VDPs represent a surge of patriotism that the nation ought to finance. To this end, the authorities announced on 9 December 2022 the creation of a Patriotic Support Fund for the war effort. They aimed to raise €152 million in 2023 to fund counter-terrorism, in particular by recruiting and equipping the VDPs. This fund, managed by the Economy Ministry, relies on donations from Burkinabé citizens and companies, and on various taxes: a voluntary 1 per cent deduction from the net salaries of public- and private-sector employees, and levies on certain consumer goods and services (mainly alcohol, tobacco and mobile phones).

Popular support for this fundraising drive is also strong. As of 30 August 2023, the Patriotic Support Fund had already collected €51.7 million, one third of the target amount. 53 This amount nonetheless appears insufficient to maintain such a large force over the long term. The economy minister estimates the quarterly payroll of the VDPs to cost €20 million, without specifying how many volunteers this calculation is based on: the current number of members or the initial target of 50,000. 54 If he means the latter, the collected sum would cover only seven and a half months of the VDPs’ activities. 55

President Traoré has raised new hopes among the VDPs and the general public. The VDPs’ ranks have swelled since he came to power, but a repeat of the same problems that the first wave of VDPs faced remains a very real risk.

C.Challenges in the Deployment of Security Forces

The distinction made between national and local VDPs seems to respond to Burkina Faso’s operational needs for a balance between offensive deployments alongside the armed forces, on one hand, and territorial defence, on the other. It is still too early to know the impact of this strategy, but the following observations are possible after almost a year of operations.

The line drawn between national and local VDPs remains theoretical in the sense that they often join forces to fight jihadist groups. Where jihadist pressure is weaker, like in the Cascades or South-West regions, VDPs can launch attacks on insurgents in remote rural areas, either independently or in conjunction with the army. They can do so also in the Centre-East, which is under more pressure. Elsewhere, where the jihadist threat is even greater, national and local VDPs work alongside the army in the large provincial towns and their immediate surroundings. 56 Deployments of national and local VDPs are often limited to these areas. Missions farther afield often consist of joint army-VDP convoys travelling on main roads, usually to protect supply convoys or escort traders. 57

Most VDPs are concentrated in Burkina’s main towns, where jihadists do not attempt to attack, such as Ouahigouya, Dédougou, Tenkodogo, Kaya and Fada N’Gourma. New recruits join the VDPs from the first wave of recruitment in these locations, along with VDPs from districts or villages vulnerable to jihadist attacks who congregate in safer towns. In this way, different VDP groups come together and support each other. 58 In June 2023, there were nearly 1,700 national and local VDPs based in Fada N’Gourma (Gourma) and more than 700 in Ouahigouya (Yatenga). 59

The authorities have often deployed these VDPs alongside the armed forces in remote areas to liberate territory.

The authorities have often deployed these VDPs alongside the armed forces in remote areas to liberate territory. The goal is often to relocate and then provide security for displaced populations. Some progress has been made but it needs consolidation in the medium and long term, as the situation in the reclaimed villages remains volatile. In the North region, the populations of some twenty villages in the Gourcy, Oula and Zogoré districts were able to return to their homes in the summer of 2023 and stay there. 60 Schools are also reopening in some of the reclaimed villages, even though this tentative reactivation of public services appears to be more an imposition by the government than something public-sector workers desire, fearing the situation may deteriorate again.

In some other regions, the returning population has been displaced again. In the East, a special GUMI police unit supported by the VDPs was redeployed to Yamba, allowing people to return to their homes. In October, however, a major attack on the GUMI-VDP coalition forced some of them to leave once more. 61

The slow progress is partly due to the complexity of these redeployments, marked by a combination of tenuous reconquests of territory and defeats at the hands of resilient jihadist groups. In small units, often fewer than the target of 100 per district, VDPs can find themselves isolated in their local areas and powerless to fend off the jihadists. Jihadists usually withdraw during resettlement missions organised by the VDPs and the armed forces, preferring to avoid confrontation at that stage. But they often return after the armed forces have left, singling out the VDPs and others who remain. Providing security for these resettlements therefore requires a sustained effort.

D.The VDPs’ Daily Challenges: Lack of Resources, Grievances and Mistrust

Despite President Traoré’s willingness to improve the treatment of VDPs, managing and deploying them continues to cause various difficulties, often similar to those encountered in 2020-2021. 62

Despite the existence of the Patriotic Support Fund, some VDPs still complain about delays in the payment of their allowances. The lags have caused some frustration, even demoralisation, although donations collected at a district level sometimes make up for these late payments. Some VDPs also report a lack of uniforms (particularly in the case of local VDPs) and protective gear (shin guards, for example). 63 They often have to share a limited number of individual automatic weapons (AK47s), sometimes of questionable quality. 64 The lack of motorbikes and fuel reduces their mobility, which is a hindrance as they are expected to patrol large areas. 65

These problems particularly affect the local VDPs; some are hoping to be transferred to the national VDPs which are better equipped, undoubtedly because of their offensive role. 66 Local VDPs sometimes vent their grievances in audio or video posts on social networks. 67 Such public expressions of discontent anger the military authorities, who have forbidden them. 68

VDPs have suffered significant casualties in jihadist attacks.

VDPs have suffered significant casualties in jihadist attacks. According to ACLED statistics, at least 644 VDPs were killed in 148 attacks between 1 January 2023 and 6 October 2023. 69 The Centre-North, North, Centre-East and East were the hardest-hit regions, with Boucle du Mouhoun not far behind.

These casualties increase the risks of defections, but so far these remain rare. No exact figures are available, but security sources estimate that between 400 and 600 VDPs – around 1 to 2 per cent of the total force – have deserted individually or in small groups. 70

Additionally, these casualties affect the cooperation between the VDPs and the armed forces. In 2021 and 2022, for example, the VDPs accused the military of failing to keep its promises, leaving them exposed on the front lines, or failing to come to their aid when they were attacked. Many incidents bear out these accusations. In Bouroum (Namentenga, Centre-North), some VDPs and an army unit, forced to withdraw from the town in 2022 because of insecurity, tried to return in May 2023. A few days later, however, the army departed from the town again, exposing the VDPs to an attack in which 31 of them were killed. 71 The VDPs accused the armed forces of abandoning them in Partiaga (East) in March, in Zekeze, near Bittou (Centre-East) where 23 civilians and VDPs were killed on 18 April, and in Bourasso, where 32 VDPs from Nouna (Kossi, Boucle du Mouhoun) were killed on 27 May. 72

In several areas, these events prompted the VDPs and a section of the population to call for dismissing certain military and police commanders. In early June, the local population and the VDPs demanded the departure of several leaders from Gourcy (North), including the town’s police chief, after the armed forces refused to recover the bodies of civilians killed by jihadists. The same happened in Mané, where the locals insisted that the commissioner step down after a jihadist attack in early 2023. 73

Relations between gendarmes and VDPs are the tensest.

Relations between gendarmes and VDPs are the tensest, as can be seen in Kompienga, Nouna, Boulsa, Gorgadji and Arbinda. Pinpointing the cause of these tensions is difficult. Following the ouster of President Damiba, the gendarmes have been less active in counter-terrorism, drawing criticism from the VDPs. Tensions between President Traoré and the gendarmerie also have the potential to boil over, as many of the VDPs – generally committed to the president’s cause – suspect the gendarmerie of remaining loyal to the former regime. In early July 2023, the VDPs accused the gendarmerie unit’s commander of collaborating with jihadists in Boulsa. 74 This incident followed a series of tensions in which the VDPs have accused the gendarmerie of not helping them after an attack on 7 July in Kogsablogo (Boulsa) in which sixteen VDPs were killed and the gendarmerie did not provide any assistance. 75

Daily relations between VDPs and the armed forces are fraught with misunderstandings about their respective roles. While the armed forces, in line with Traoré’s commitments, prohibit the VDPs from patrolling on their own, the VDPs criticise the military for being too afraid or jealous to act. They also accuse several officers of remaining loyal to the former regime. 76 The VDPs also complain that certain military units are condescending, mocking and even disregarding the intelligence that they provide. 77

Civilian casualties, combined with frustration at being under-resourced and the difficult relations with the defence and security forces, risk exacerbating resentment among the VDPs. In the long term, such discontent could lead to more defections than those recorded in 2023.

These grievances have so far been directed less at Traoré, who enjoys the support of most VDPs, and more at the local units of the security forces. However, if the discontent is allowed to fester and spread, the disgruntled elements could end up directing their criticism at the head of state, as happened with former President Kaboré, whom the VDPs accused of abandoning them.

III.Defending the Nation at the Expense of Social Cohesion

A.Community Prejudices Exacerbate Divisions

The VDPs appear to be indispensable in the anti-jihadist fight, but they have often been accused of inflaming social tensions in the areas where they operate. One critic is former Prime Minister Albert Ouédraogo (January-September 2022), who said in an interview in August 2022: “These groups [VDPs] must reflect the diversity of the community at the district level. Because we’ve noticed that a kind of community factionalism has developed within the VDPs. And we’re aware that this has had some negative effects”. 78 As noted above, President Damiba was also critical of the VDPs: “despite their bravery, sometimes [they] are manipulated to settle scores between communities, […] upsetting delicate balances achieved by our predecessors”. 79 Crisis Group also highlighted this problem in a report published in 2020. 80

VDP recruitment has never respected the balance within local communities and has almost systematically excluded pastoralists. The Mossi – making up 50 per cent of the population – are the majority in the VDPs at a national level, reflecting the country’s demographics. The Fulani – Burkina’s second-largest community, comprising around 10 per cent of the population – are generally not recruited, however. The discrepancy is particularly marked in areas where they are the majority or have deep roots.

In the Sahel and Centre-North regions, the Koglweogo consist mainly of Mossi and Fulsé, while the Fulani and the Touareg are largely excluded – an imbalance accentuated when the VDPs were established in 2020. In the Oudalan and Seno provinces, the VDPs created in 2021 are mainly Songhai et Gourmantché, with very few Fulani (the Yagha province being an exception). 81 In the second wave of VDPs, the recruitment of new communities (Lobi, Bisa) again discriminated against the Fulani, except in a few cases such as in Kampti (South-West). 82

In many VDP strongholds ... the Fulani are deliberately kept out of the auxiliary corps because they are suspected of collaborating with the jihadists.

The Fulani are excluded mainly because VDPs have accused them of forming the majority of jihadist groups, leading Koglweogo and later VDP groups to oppose their recruitment. As a result, in many VDP strongholds, such as Arbinda, Gorgadji or Djibo in the Sahel, Barsalogho in the Centre-North, Titao or Sollé in the North, the Fulani are deliberately kept out of the auxiliary corps because they are suspected of collaborating with the jihadists. 83

The authorities have never taken action to correct these communal prejudices. In 2017, several prominent Fulani figures from the Sahel wanted to organise themselves into self-defence groups, but President Kaboré refused to support the initiative. 84 In 2022, President Damiba expressed a desire to recruit Fulani into the VDPs, but to no avail. 85 Since taking power, President Traoré has made no public statement on the issue, but he has called on Fulani groups to urge their “brothers” in jihadist groups to lay down their arms. 86

After years of exclusion and abuse at the hands of the Koglweogo groups and the VDPs, many Fulani have given up on the possibility of joining the VDPs. Some Fulani leaders explain that their communities steer clear of the VDPs out of fear of being stigmatised, isolated or even threatened. Joining the VDPs would not be enough to protect their communities from these groups and would in effect expose them to even greater jihadist violence, targeting VDPs in particular. 87 This reluctance to join the VDPs also often makes the Fulani suspect in the eyes of the authorities. In late 2022, Fulani applicants were rejected on the grounds that they might try to infiltrate the VDPs to support the jihadists. 88

This lack of inclusivity is also due to the misapplication of regulations. In theory, the creation of VDPs is subject to the approval of local populations through “general assemblies chaired by the Village Development Committee or the District Council”. 89 This local filter is designed to check the character of applicants and ensure that all communities are represented within the VDPs. 90 These general assemblies have never been held, however, indicating that the authorities do not consider them a priority. The District Council’s role has been questioned since the dissolution of regional and local authorities on 1 February 2022. 91

Even without general assemblies, however, mayors, local councillors and traditional leaders with the local army and gendarmerie commanders worked together to assemble the VDPs during the two preceding presidential regimes. 92 This consultation mechanism with prominent local figures has largely disappeared since the arrival of President Traoré. The lack of consultation is certainly understandable at the level of the national VDPs, since they are not recruited to serve in their home communities. It creates problems, however, for local VDPs, who serve in their own communities and need to be accepted by all prominent local figures. In this case, the Brigade of Homeland Vigilance and Defence is directly responsible for recruiting on the basis of individual applications submitted to the regional authorities. The Brigade is also involved in certain cases with high-profile local figures who do not represent the diversity of the community in a specific area. 93

Gaining political power or controlling the local economy is a hidden agenda in the fight against terrorism.

Community biases among the VDPs are evident from their involvement in solving local problems unrelated to counter-insurgency activities. Gaining political power or controlling the local economy is a hidden agenda in the fight against terrorism. Given the widespread pressure over access to resources (land, water, forests, cattle) that are no longer under state control, VDPs become a way of “settling scores”, according to the founder of the Koglweogo in the East region. 94

This phenomenon erodes social cohesion. 95 In the Centre-North, North, Grand Ouest (Boucle du Mouhoun, Hauts Bassins, South-West) regions, and in Gourma province of the East region, non-Mossi communities see the (predominantly Mossi) VDPs as a means of strengthening the Moagha base in the peripheral areas where they are in the minority. 96 Recently, the South-West and Hauts-Bassins regions have seen land evictions and killings, pitting Mossi VDPs against VDPs from the Indigenous Bobo and Lobi communities. 97 In Oudalan province, Touareg and Fulani communities have accused the majority Songhai VDPs of pursuing a community-based agenda, particularly in Markoye. 98

Amid this intercommunal competition, some groups overcame their initial reluctance to create VDPs, forming such units so that non-Indigenous (often Mossi) communities would not beat them to it. The Gourmantché in the Eastern region and the Seno province (Sahel) are one case in point, while the Dozo in western Burkina are another. 99

The war economy established by some VDP groups has fuelled intercommunal divisions, particularly when this economy is based on rustling cattle, a resource of great economic and cultural significance. Cattle are often property of nomadic communities, but coveted by jihadists. VDPs have also sometimes stolen and hidden cattle, working in conjunction with members of the armed forces and mayors. 100 In this respect, the mayor of Kelbo (Soum province) has been the subject of a public inquiry by the Collectif contre l’impunité et la stigmatisation des communautés, or CISC, an organisation to promote social cohesion among communities in Burkina, but his involvement has not yet been legally established. 101 These criminal practices not only undermine the public authorities, but also create strong tensions at a community level, especially as they often go unpunished. Cattle rustling has declined in 2022, mainly because there are fewer animals to steal now that livestock numbers have been decimated by theft, but it still occurs. 102

B.VDPs at the Centre of Communal Violence

The Fulani stay away from the VDPs because they are particularly vulnerable to the violence these groups commit alongside the armed forces, as evidenced by several recent incidents of violence against this community.

A few months after the VDPs were created in January 2020, the sheikh of the town of Tanwalbougou (East region) advised his followers to remain neutral. Following this guidance, the Fulani of Tanwalbougou refused to join either the VDPs or the jihadists. But the armed forces and the VDPs, perceiving this neutrality as a proof of complicity, went on to kill around twenty Fulani civilians, including some close to the sheikh. 103 In Nouna (Boucle du Mouhoun), several human rights organisations accused the VDPs of killing more than 100 Fulani on 30 December 2022. 104 In Ouahigouya (North), at least 30 Fulani were abducted between November 2022 and early March 2023. They have been missing since then. 105 Between April and June 2023, in the Hauts-Bassins and Centre-East regions, armed individuals summarily shot Fulani herding cattle or travelling in buses. Some observers have blamed the VDPs. 106

Attacks on civilians are not only linked to ethnic identity. The VDPs and the armed forces have targeted men and women suspected of doing business or having personal ties with jihadists. In the Bam province (Centre-North), in summer 2022, the armed forces and the VDPs violently attacked civilians of various backgrounds whose occupations (such as butchers or fuel sellers) might have enabled them to provide logistical support to the jihadists. 107 In August 2023, similar suspicions arose regarding the victims of the Tougouri massacre (Centre-North). 108

The place of residence, particularly when located close to jihadist areas, may be another explanation for these reprisals. In March 2023, residents of Karma (North) reported that the armed forces had killed at least 146 non-Fulani civilians (including women and children) execution-style, an allegation that has yet to be confirmed. 109 The armed forces had accused them of failing to establish VDP units or to warn them of an attack that had killed several dozen VDP recruits one week prior. 110 If these allegations are confirmed, they could reflect a strategy by the armed forces to target civilians living near areas under jihadist influence and unwilling to take a clear position in the conflict, in support of the army and the VDPs.

The personal experiences of new VDP recruits also partly explain the spread of violence. These individuals have often suffered themselves from jihadist attacks, often losing close family or friends, or being displaced from their homes, leaving them with deep grievances. 111

VDPs have never been punished for the acts of mass violence allegedly involving them.

Penalties have increased significantly in recent months, even though VDPs have never been punished for the acts of mass violence allegedly involving them. More than a hundred VDPs have been brought before the authorities to face disciplinary measures ranging from dismissal to prison sentences. 112 Some have gone to jail for theft, selling their equipment, rape and homicide. In 2023, five VDPs were imprisoned in Ouahigouya for killing an old man. 113

Punishments are often the result of the influence exerted by victims’ relatives or a proactive approach by security agents in the area. 114 Nevertheless, no one responsible for massacres has yet been brought to justice. Investigations are under way, but no progress has been made. The systems in place for “beneficiaries” (local populations) to control the VDPs’ activities, as decreed in June 2022, have never been implemented. 115

The fact that VDPs now operate alongside the armed forces does not improve their treatment of civilians. The armed forces have long been accused of attacking civilians whom they suspect of collaborating with jihadists. Such accusations, which are often well-founded, were circulating even before the VDPs became central to counter-insurgency operations. 116 According to the ACLED database, the armed forces killed at least 500 civilians between January 2019 and April 2020. 117 Human rights organisations still frequently accuse them of abuses and massacres, including the aforementioned case in Karma in March 2023 and the massacre in Zaongo (Centre-Nord) on 6 November 2023. 118

These acts of violence lead to reprisals that help attract new recruits to the VDPs but also to jihadist groups. 119 Each massacre undermines social cohesion and perpetuates a cycle of revenge among rival armed groups. Without local mediation, these intercommunal conflicts will only keep worsening.

C.Civilians Associated with VDPs and Highly Vulnerable to Jihadist Violence

President Traoré has invoked patriotism in his calls upon the Burkinabé population to support the military’s campaign to retake territory. The rhetoric has been divisive, with critics of his approach – and even those who prefer to take no position – accused of being “apatrides” lacking loyalty to their country. 120

Asked to take sides, communities can no longer remain neutral in the war on terrorism. Previously, they could oppose the creation of VDP units to protect themselves from possible jihadist reprisals. 121 They can no longer do so. Those who remain reticent about creating VDPs risk being considered enemies of the nation and suffering retaliatory action. On 6 November 2023, at least 70 civilians (including women and children) were massacred in the village of Zaongo (Centre-North) after they refused to create VDP units in order to avoid having to flee their homes, as had happened in neighbouring villages. 122 More than once, the authorities have arrested a traditional leader who opposed the creation of VDP groups in Djibo (Soum). 123 On 1 April 2023, the authorities arrested the founder of the Koglweogo, who opposed the VDPs and was later reported missing in Fada N’Gourma (Gourma). 124 Even so, communities occasionally still oppose the creation of VDPs. 125

Communities can no longer negotiate local agreements with the jihadists like they used to. In Pobé Mengao (Soum), Thiou (Yatenga) and Titao (Loroum), where these dialogues led to local agreements in 2021, the jihadists succeeded in negotiating the demobilisation of the VDPs. 126 These local agreements certainly benefited the jihadists by tipping the balance of power in their favour. But they also provided security for the local population, allowing them to leave their towns to do agricultural work on condition that they respect Sharia law and do not collaborate with the armed forces. 127 The current regime has put an end to such local dialogues, which the former minister for reconciliation and social cohesion during Damiba’s presidency had supported and even expanded to other regions. Some participants in these dialogues have since been arrested while others are still wanted, making it virtually impossible to launch new rounds of talks, with the exception of a tentative initiative in early October 2023 in the Yagha province. 128

Since 2015, the number of civilians killed has risen steadily to record levels.

Communities are paying a high price for their inability to remain neutral or engage in dialogue with the jihadists. Since 2015, the number of civilians killed has risen steadily to record levels, further increasing resentment and a thirst for vengeance. According to ACLED data, at least 1,527 civilians were killed during the first seven months of 2023, compared to 1,414 civilians in 2022, and 757 in 2021. 129

Violence against civilians has evolved significantly: before President Traoré came to power, the armed forces, the VDPs and IS Sahel were killing more civilians than JNIM. JNIM rarely attacked civilians on a large scale. In areas without VDPs, JNIM mainly attacked the armed forces and symbols of the state’s presence (mayor’s offices, schools) and its representatives (public officials, elected politicians). In areas where VDP units had been assembled, JNIM was responsible for massacres, but only rarely – as in Kodyel (Komondjari) in May 2021 and Solhan (Yagha) a month later – and senior figures within the group had not authorised these acts. 130 The IS Sahel, meanwhile, was already systematically using this tactic, launching multiple attacks on civilians. The most extreme example was Seytenga, which the group struck twice, in June 2022 and April 2023. 131

In 2023, most civilians were killed by the jihadists, particularly JNIM. 132 Following the recruitment of the second wave of VDPs, jihadists started attacking civilians more systematically, although jihadist violence against civilians was already increasing slightly during Damiba’s presidency. JNIM mainly abducts and kills individuals connected to the VDPs, either through their family’s relations or through their involvement in recruitment or support for the VDPs. The group has claimed responsibility for this strategy. Shortly after announcing the recruitment of 50,000 VDPs, for example, JNIM produced a video threatening civilians who assisted the Burkinabé authorities in their anti-terrorist operations. 133

Civilian populations also bear the brunt of JNIM’s increasing number of blockades. With rare exceptions, as in Djibo in 2020, areas under partial or total siege are those where VDPs have assembled. 134 In addition to harming civilians economically, these blockades also create insecurity. When merchants are banned from entering the villages, the local population suffers from severe food insecurity. When people venture out in search of water, firewood or food, they are regularly abducted or killed, sometimes by improvised explosive devices. Women are often the victims.

In their efforts to provide security, the authorities have so far failed to resolve the dilemma of how to reclaim land without endangering the population. The state – working through the VDPs – appears to be dragging communities into the war at the risk of making them more vulnerable, both in terms of their security and their economic wellbeing.

IV.Limited Leeway for Foreign Partners

Traditional partners find themselves in a delicate position in Burkina Faso. They are well aware of the risks of massively arming civilians and are thus reluctant to agree to the authorities’ requests to arm VDPs. 135 Neither do they wish to abandon all security cooperation, not only because they have heavily invested in security in recent years, but also because they fear that Burkina Faso may turn toward Russia or other new partners.

A.The Traditional Partners’ Cautious Approach to the Issue of Arming Civilians

Even before the jihadist threat emerged, Western partners were interested in security issues in Burkina Faso, notably community-based policing. Since 2003, Ouagadougou has developed an ambitious policy in this area. In 2010, it issued a national security strategy that aimed to expand community-based policing across the country. Several donors, including Canada and the Swiss NGO Coginta, backed this approach early on. 136

The authorities failed, however, to monitor the progress of these initiatives on the ground. As a result, they collapsed and people decided to take matters into their own hands by setting up the Koglweogo instead. In 2016, the authorities responded by passing a decree to formalise the role of the Koglweogo within Local Community Security Structures under mayors’ authority. Denmark and the UN Development Programme notably supported the authorities in implementing this decree.

The emergence of the jihadist threat after 2015 prompted many international actors to step up their investments in security and defence. Although their efforts were focused on anti-terrorism and counter-insurgency, they did not give up on the issue of local security.

[Western partners] are largely convinced that recruiting tens of thousands of VDPs will weaken Burkina Faso’s social fabric and intensify intercommunal violence.

There was a significant shift, however, with the creation of VDPs in 2020. The enthusiasm of most Western partners waned as they struggled to position themselves in relation to the Burkinabé leaders’ newfound reliance on VDPs. Some partners refuse to support arming civilians on principle, while others fear the risks that come with an increased reliance on these volunteers for counter-insurgency operations. They are largely convinced that recruiting tens of thousands of VDPs will weaken Burkina Faso’s social fabric and intensify intercommunal violence. 137 To mitigate this risk, the European Union has sought to support dialogue between the VDPs and communities in various regions. 138 It has also tried to support local forms of “co-production” of security between communities and the state that are more inclusive than the VDPs. 139

Moreover, the EU has expressed worries about the repercussions of these decisions for military cohesion. One European diplomat remarked: “Considering their numbers, the VDPs are becoming the core of the security apparatus and the regular army its margins”. Despite such concerns, Western partners have little to no means of influencing the authorities’ thinking.

Although Burkina’s partners are reluctant to support the VDPs, the country’s leaders expect them to help expand these armed civilian groups. Since the coups of January and September 2022, Burkinabé authorities have tailored their requests for “war support” to ask for military equipment for both the armed forces and VDPs. 140 Yet for entities and countries which, like the EU, refuse to arm civilians on principle, it is impossible to fulfil such requests. 141 Burkina’s leaders find this principled stance hard to accept, having designated VDPs as an official “auxiliary corps” under the authority of the defence and security ministries.

B.Assisting the New Authorities without Supporting the VDPs: A Dilemma for Western Partners

Amid concerns surrounding the VDPs, the attitudes of Western partners toward the Burkinabé authorities have also changed following the two coups in 2022. These events substantially complicated security collaboration for several states and multilateral institutions. Many have suspended their cooperation or are reluctant to consider new projects to replace those nearly completed.

France, previously a privileged partner of Burkina Faso, finds itself completely sidelined, without any role in security cooperation. It no longer has an ambassador in Ouagadougou, nor a military attaché, after the latter was expelled in September 2023. 142 The 400 French soldiers in Operation Sabre packed up in February 2022, concluding their fifteen-year presence in the country. 143 This rupture between the French and Burkinabé authorities extends beyond security cooperation. Major French media outlets, eg, Radio France Internationale, have been suspended, and between August and December 2023, France issued no visas to citizens of Burkina Faso. 144 The prospects for improving relations between the two nations in the coming months seem bleak. Distrust of Paris serves as political fodder for the current authorities, who rally their base with the notion of a second declaration of independence marking a final break with the former colonial power.

For its part, the U.S. suspended its military cooperation with Burkina Faso after the first coup in January 2022. It took almost three weeks, however, for the U.S. to qualify the ouster of President Kaboré on 24 January as a coup d’état. Only after 18 February 2022 did the State Department cut most of its aid to Burkina Faso due to a law requiring that assistance to a nation be suspended when its elected head of government has been overthrown by the military. 145 U.S. aid to Burkina Faso is now minimal. 146

The U.S., however, has not wavered between pragmatism and principle in Burkina Faso, as it has in Niger since the 26 July 2023 coup.

The resumption of U.S. aid, including military assistance, hinges on the restoration of constitutional order, which depends on highly uncertain future elections. The Burkinabé leadership has repeatedly stated that organising a presidential election requires a significant improvement in security. 147 The U.S., however, has not wavered between pragmatism and principle in Burkina Faso, as it has in Niger since the 26 July 2023 coup in that country. Nonetheless, it remains diplomatically active, notably through the ambassador, who has been meeting regularly with the current leadership. 148

After the January 2022 coup, the EU halted its security cooperation, in particular its support for the gendarmerie, although it maintained all projects initiated before the first coup. The EU’s position remains unchanged to this day. Discussions quickly resumed between the EU and Ouagadougou to relaunch security cooperation, however. 149 The agreement between Burkina Faso’s transitional government and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) regarding a 24-month electoral timetable and a return to civilian rule by 1 July 2022 largely justified this stance. 150 The EU did not want to sabotage the recent efforts to protect the country from jihadist expansion as that would also entail risks for the rest of the region and even the EU itself.

The second coup in September 2022 derailed the prospect of resuming security cooperation with Burkina Faso. Two months later, the new regime sent a letter to the EU delegation requesting arms support, specifically automatic weapons and helicopters. 151 Despite the challenging state of security collaboration, the EU chose not to reject this plea outright. Instead, it sent an interdepartmental mission to Ouagadougou at the end of February 2023, proposing security cooperation through the European Peace Facility. But President Traoré’s support for the perpetrators of the coup in Niger on 26 July 2023 brought these discussions to a halt. 152

While Western partners hesitate, reduce or suspend their cooperation with the new authorities, the latter are increasingly turning to Russia. At the Russia-Africa summit in July 2023, President Traoré made a notable rapprochement with Moscow, going so far as to declare his support for Russia’s war in Ukraine. On 31 August 2023, the Russian deputy defence minister made an official visit to Ouagadougou, concluding a rapprochement in several strategic areas, including military cooperation. In early November 2023, Burkina Faso’s defence minister, Kassoum Coulibaly, travelled to Moscow to meet his Russian counterpart. 153 Not long after, Russian instructors reportedly arrived in the Burkinabé capital, ostensibly to support the authorities’ war effort, but perhaps also to serve as a security detail for the top leadership. 154 Russia may decide to provide weapons for the Burkinabé armed forces, a move that could also benefit the VDPs.

Western partners are following these developments with concern. They are reluctant to endorse the regime’s current security strategies, particularly as regards the VDPs. Yet they are also wary of abruptly severing ties at the risk of forfeiting past investments and being replaced by competitors. Consequently, Western partners are grappling with a dilemma that, thus far, they are unable to resolve.

V.Curbing the Counterproductive Effects of VDPs

Back in 2020, Crisis Group anticipated that the creation of VDPs would exacerbate violence and incite jihadist attacks. 155 The use of VDPs is undoubtedly one of the major causes of the alarming rise in violence against civilians since 2020. But at this stage, the authorities have banked on these volunteer units too much to backtrack. The army’s deficiency in troop strength means they have no choice but to rely on VDPs to protect the territory. To limit the damage caused by the use of VDPs, the transitional authorities could draw inspiration from the measures outlined below.

In the immediate term, they could first slow the rate of recruitment, integrate more well-trained VDPs into the army and improve monitoring mechanisms to better protect civilians. In the long term, they could also consider how best to demobilise other recruits. Simultaneously, the authorities should reassess their deployment of the regular armed forces (including the internal security forces), which remain the best instrument for a state to secure its territory. Lastly, they should tighten controls on VDPs to curb abuses that undermine both social cohesion and the country’s stability.

A.Striking the Right Security Balance

The massive recruitment of VDPs, potentially nearly double the number of defence and security forces, poses a threat to military cohesion and national stability. 156 The authorities should scale back recruitment and reassess their goal of mobilising 100,000 VDPs, as announced by the prime minister in May 2023. Pursuing this target seems ill advised considering budget constraints, local tensions between army troops and VDPs, and negative effects of those tensions on social cohesion. To compensate for a drop in VDP recruitment without compromising national security, the authorities should make better use of existing armed forces. These personnel, already accounted for in the state budget, generate no additional expense.

Furthermore, the gendarmerie and police are still too far removed from the fight with jihadist groups, despite the supposed mobilisation of all defence and security forces. From 2015 to 2019, the gendarmerie showed that it could play a key role in counter-insurgency, despite facing accusations of human rights violations, triggering further jihadist attacks. 157 But a lack of trust between the leadership and the gendarmerie inhibits the full use of this force, which is meant to have closer contact with the population. Here, too, a more open dialogue with the gendarmerie would help improve matters. Moreover, the authorities should further pursue counter-insurgency efforts launched in early 2023 to mobilise the police by increasing the number of GUMI units. This elite force, comprising an estimated 20,000 individuals, should be put to better use in the conflict. 158

At the same time, the authorities should continue to integrate the best-trained VDPs into the army, which is planning to enlist large numbers of troops in the coming years. Such an approach would help improve the training and oversight of VDPs, provided it involves rigorous vetting. Background checks are essential to avoid recruiting individuals involved in serious crimes such as extrajudicial killings, torture and sexual violence.

Deploying the VDPs nationwide could mitigate their involvement in local intercommunal conflicts, which often underpin much of the violence against civilians.

Once integrated into the army, deploying the VDPs nationwide could mitigate their involvement in local intercommunal conflicts, which often underpin much of the violence against civilians. Such recruitment is no panacea, however, as the army itself is accused of violence against civilians. The positive effects of such integration therefore depend very much on the armed forces changing their approach to better protect civilians, particularly those living close to areas where jihadists are active.

Integrating more VDPs would address the need to increase the army’s manpower while recruiting personnel who have battlefield experience. It would also enable the state to reduce the number of VDPs, easing the tensions between these auxiliary troops and the armed forces. Once VDPs are deployed as army troops outside their native region, however, they lose much of the advantage they bring in knowledge of the terrain. As they are significantly more costly, they will also place a greater strain on the state budget, already burdened by security spending.

Some of these contingents could be integrated into the army on renewable fixed-term contracts, so that the country does not end up with an overstaffed military if the security situation improves in five or ten years. At the same time, the authorities could start considering ways of retraining and reorienting contracted army personnel at the end of their employment. Another solution would be to transform the VDPs into Local Community Security Structures. Under the supervision of the police or gendarmerie, such community-based policing units “provide a security presence, gather information, and can arrest people in cases of obvious offence”, according to the 2016 decree. Their members are not armed, except for individuals who have a weapons permit.

The authorities should also encourage different entities to enlist VDPs, such as the gendarmerie (despite current tensions and given the appointment of a new gendarmerie chief), the police or even the water and forestry services, tailoring recruitment to the needs of each corps. Local VDPs, for example, could join police forces that operate primarily in urban areas and not directly engaged in counter-jihadism efforts, except for its elite GUMI units. To resolve the current crisis, Koglweogo-like local security initiatives or police auxiliaries, who have proven their worth in the fight against crime, could prove to be key actors. They may be needed to combat lingering jihadist factions whose members often transition into banditry, benefiting from the widespread distribution of military-grade weaponry or smaller firearms.

B.Preventing VDPs from Undermining Social Cohesion

The VDPs, much like the armed forces, face persistent accusations of perpetrating violence against civilians. Investigations and prosecutions have been inadequate to date. The authorities must not tolerate these crimes. Winning the war with jihadists cannot come at the population’s expense. They should recognise that every act of violence against civilians plays into the jihadist groups’ hands.

Immediate, tangible actions are needed to reassure people who feel targeted by the VDPs and the regime. In particular, the military prosecutor should initiate investigations of civilian massacres allegedly involving VDPs and the army, such as the incident in Nouna on 31 December 2022, and proceed with arrests and indictments where warranted. Such actions would send a strong signal to potential perpetrators about accountability. Simultaneously, the women and men who are victims of violence would gain a greater sense of support from the authorities.

At the very least, the Burkinabé leadership should bolster mechanisms to oversee the VDPs’ actions. First, they should set up community-based monitoring mechanisms, as outlined in the decree of June 2022. 159 Such mechanisms should systematically include staff from human rights organisations or individuals locally engaged in this field, alongside other local representatives, to ensure impartiality.

The authorities should also ensure that recruitment [of VDPs] does not undermine social cohesion.

The authorities should also ensure that recruitment does not undermine social cohesion. To that end, community representatives, forming part of “village assemblies”, should approve VDP enlistees so that they have the support of the people they are supposed to protect. Future recruitment drives should mandate a minimum level of ethnic balance, in particular by ensuring that Fulani candidates are considered on an equal footing with others. Although Fulani are increasingly reluctant to join the VDPs, there are still potential candidates among them.

The authorities should also work to stem ethnic violence and renew contact with communities that are excluded from or refuse to join the VDPs, in particular the Fulani. They could promote the creation of inclusive local dialogue forums representing all communities. Ideally, the participants themselves should come from these communities to ensure the credibility of the forums. Nationally recognised human rights organisations such as the Mouvement Burkinabé des droits de l’homme et des peuples, the Collectif contre l’impunité et la stigmatisation des communautés and Tabital Pulaku should systematically be part of these committees to ensure their representativeness.

As a means of rebuilding social ties, displaced Fulani should also be invited to participate in community initiatives involving the armed forces and VDPs. One such initiative is “Production de défense de la patrie contre l’insécurité alimentaire” (Producing to Defend the Homeland from Food Insecurity), a program aiming to mobilise the military and VDPs to secure agricultural production. 160

A preventive approach will be crucial for preserving social cohesion in areas where jihadist groups are less active, such as certain provinces in the Centre-West, Centre-South and South-West regions, as well as the Plateau-Central region. In these areas, the authorities should enforce the principle of “approval by the local population”, stipulated as a precondition for assembling VDPs by the law of December 2022. They could set up “village assemblies”, provided for in the June 2022 decree, which would be responsible for deciding whether to approve the VDPs. If an assembly decides not to, the authorities should respect this choice in the interests of social cohesion, given that jihadist violence has not yet affected these areas. If an assembly approves a VDP unit, but certain communities (eg, Fulani) refuse to join, the authorities should ensure the VDPs understand and respect that choice so as not to stigmatise the communities concerned.

C.Identifying an Area of Cooperation for International Partners

Burkina Faso has a long tradition of engaging with foreign partners both regional and international. They share a common interest in preventing the further escalation of violence and insecurity, but have different ideas about the factors contributing to this situation. Foreign, particularly Western, partners should step up their cooperation to defend their shared positions based on the concern that the continued use of VDPs and recurring violence against civilians will aggravate insecurity rather than resolve it.

Western partners, including the EU, that wish to preserve relations with Ouagadougou should display their willingness to strengthen internal and external controls on VDPs, without arming them. The Burkinabé leadership may not drop its previous requests for arms. Nevertheless, the country’s partners should continue to help coordinate and monitor VDP activities in the hope that the authorities will come to recognise their importance.

In terms of social cohesion, foreign partners, and particularly the EU, could promote mechanisms to better control the actions of VDPs without providing operational support. Such mechanisms will be essential to help reduce VDP abuses against civilians. The country’s partners could propose to the Burkinabé authorities that they help establish and manage village assemblies and civilian monitoring mechanisms, both of which are provided for by law. With the approval of Burkinabé government bodies, the EU could also play a role by supporting initiatives to reintegrate VDPs into civilian life.

[International] partners should step up support for human rights organisations so that their activities can cover all the districts where VDPs operate.

In any case, partners should step up support for human rights organisations so that their activities can cover all the districts where VDPs operate. These organisations have played a life-saving role in recent months by calling on local authorities to take action as soon as civilians disappeared or faced violence. 161 Nevertheless, partners must take care not to place these organisations in danger, given the current countrywide curtailment of freedoms.

The regime’s increasingly hard-line stance is prompting many partners to keep cooperation to a minimum, particularly in the security field. The EU is particularly wary, although some member states also fear that reduced cooperation could benefit Russia, perceived as a serious rival since it demonstrated its interest in the Sahel at the Russia-Africa summit in July 2023. Beyond geopolitical rivalries, the real peril for the region and its partners lies in the potential collapse of the country, which would have repercussions for its neighbours, particularly the coastal states to the south. Security cooperation certainly cannot come at any cost, and the possibilities have considerably dwindled due to the double-edged sword of employing VDPs. Nevertheless, dialogue and the pursuit of compromise should take precedence over severing partnerships or isolating Burkina Faso.

Finally, international partners should better coordinate their approach toward Burkinabé authorities, in particular by joining forces to encourage greater control and independent investigations when VDPs or armed forces are accused of crimes. The U.S., which still wields significant political clout and has no colonial past in the region, could head such a coalition of partners to respond more assertively, aiming to curb violence and shed greater light on alleged VDP abuses in the country.

VI.Conclusion

VDPs have become a pillar of the anti-jihadist fight in Burkina Faso. Yet they pose major risks to the country. The announced recruitment of a large number of new VDPs – ranging from 50,000 to 100,000 – will make it increasingly difficult to control these groups. Many accuse them of involvement in numerous crimes against civilians.

Backtracking is not a possibility in the short term. Given the VDPs’ entrenchment in the security apparatus, swiftly dismantling the units is unrealistic and potentially perilous. Without them, localities under blockade, along with many others, would not withstand jihadist attacks for long.

For VDPs to positively contribute to counter-insurgency efforts, however, Ouagadougou must take measures to better control them and enhance civilian protections during their operations. The Burkinabé authorities might face risks in doing so, as the auxiliary corps provides significant support for the regime, but that is the price to pay for stabilising the country.

Dakar/Brussels, 15 December 2023