Where did General Gowon come in for blame?

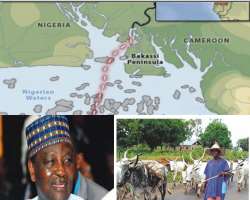

There is a recent video clip that is currently making the rounds in the social media. In that video recording, the author claims he was intrigued by the fact that Nigeria ceded Bakassi Peninsula to Cameroon, and he also researched on grazing routes in Nigeria in order to be more enlightened on what grazing routes were all about. The situation as it appeared seemed entrenched in the domestic policy of the Buhari government and had become a challenge Nigerians must find a solution to.

From his research, according to the author, he discovered that during the Nigerian civil war, General Yakubu Gowon had been briefed that Biafra would never fall unless Port Harcourt was conquered. And so, he said Gowon sent emissaries to the Cameroonian government, asking it to give Nigeria access to Port Harcourt through its waterways. The Cameroonian government agreed, but only on condition that the Bakassi Peninsula would be ceded to Cameroon in compensation. Gowon conceded. The agreement was signed and sealed and Cameroon quickly took possession of the document that ratified the agreement.

The author also tried to convince Nigerians that under General Gowon’s watch, the Nigerian government signed another agreement with the Republics of Chad and Benin. Chad and Benin were to supply it with mercenary fighters to help prosecute the war against Biafra. The Nigerian government agreed with the Chadians to create a grazing route for Arab African herdsmen all the way from Chad through the North to the South of Nigeria. He said this was why herdsmen who were not even Nigerians could match with impunity on Nigerian villages in the north and slaughter the people. The authorities were unable to do a thing about the situation because these intruders had the documents authorising them passage into and through Nigerian lands signed by the Nigerian government with Gowon’s mandate.

Angrily, the author demands that Nigerians put pressure on General Gowon to explain what happened during the civil war. He said because the Cameroonian and Chadian governments had these documents, the hands of General Obasanjo and all the other Heads of State who ruled Nigeria after him were tied. They could not help the situation. So, the Nigerian public must hold General Gowon to ransom. He must explain to them how Bakassi was ceded to Cameroon and why grazing routes were created through Nigerian lands for Fulani herdsmen who were not even Nigerians.

Honestly, I think that video clip and the message it was sending out to Nigerians and friends of Nigeria could mislead the public, even though the author had no such intention. The fact about Bakassi, as far as it is known, is that the 1,600 kilometre long peninsula lies between Calabar in Cross River State of Nigeria and the Rio del Ray Estuary in Cameroon. Both Nigerians and Cameroonians always lived happily on the peninsula. Not that Bakassi is a great expanse of land but still it is important because it is rich in oil and other mineral resources.

With a fast growing population estimated at 300,000 and a continuous increase in social and business activities, Bakassi soon became a conflict area between Nigeria and Cameroon. The conflict almost degenerated into war between the two sister-countries at some point. But in 1994, Cameroon decided to drag Nigeria to the International Court of Criminal Justice at The Hague to contest the ownership of Bakassi alongside five other complaints it made against the Nigerian government.

The Cameroonian government claimed that Bakassi was its land because during the colonial era, the British government had ceded Bakassi to Germany after signing the Anglo-German agreement in 1913. Germany later ceded Bakassi to France. And afterwards, France ceded the peninsula to Cameroon. Cameroon had documentary evidence to prove its claim. The Nigerian government claimed the peninsula belonged to it on the ground that it had had possession of the land for a very long time and that Nigerians predominantly inhabited the peninsula.

It became obvious that the conflict between Nigeria and Cameroon over the peninsula would lead to war. Many developed countries like Russia and China took sides with Cameroon. That put Nigeria in a precarious position, should the situation snowball into war. Cameroon had the documents that fortified its claim as the owner of the land. It also had five other cases against Nigeria, not just the issue of Bakassi alone.

The case lingered in the International Court for eight years. Then, relying on documentary evidences made available to it as the case progressed, the world court decided that Bakassi belonged to Cameroon on 10 October 2002. That judgement did not go down well with the Nigerian government. But the government could do nothing about it as there was no scope for an appeal against a judgement by the International Court. Whatever was its decision is final. In 2008, after series of consultations and dialogues, General Olusegun Obasanjo signed the document that came to be known as the Green Tree Agreement and Bakassi was officially ceded to Cameroon.

Since then, many Nigerians have continued to express their anger and disgust that Nigeria surrendered Bakassi to Cameroon on a platter of gold. They saw it as weakness on the part of the Nigerian government. In an attempt to educate Nigerians on the issue which had continued to be a source of disillusionment for many, about two years ago, Tunde Ajaja of the Punch newspapers interviewed Prince Bola Ajibola, 82, on the resolution of the Bakassi conflict between Nigeria and Cameroon. Justice Ajibola is one of the few Nigerians who had the rare experience of being a judge at the International Court of Criminal Justice at The Hague. Fortunately, he was one of the 17 judges who presided over the Nigeria-Cameroon conflict at The Hague. And he was obviously in a position to know what actually transpired.

According to that interview, published in the Punch newspaper edition of 29 October 2016, all the documents and evidences presented before the court pointed to Cameroon as the owner of the peninsula. Notable Nigerians had also confirmed that Bakassi did not belong to Nigeria. Teslim Elias who was the Attorney General and Minister of Justice at the time was one of the people who gave evidence to the fact that Bakassi was not a part of Nigeria. Even before he declared so, Jaja Wachuku who was the Foreign Affairs minister at the time had already addressed the issue. In 1962, two years after Nigeria got its independence, he confirmed that Bakassi was part and parcel of Cameroon. Even the map of Nigeria at the time showed that Bakassi was not a part of Nigeria.

So, for anyone to stand up in the broad daylight and accuse General Gowon of ceding Bakassi to Cameroon in order to have access to Port Harcourt is, to put it mildly, quite uncharitable. It does not appear from historical evidences that any such transaction took place.

And while Nigerians address the issue of herdsmen and grazing routes, they must agree with their erudite Professor Wole Soyinka who has suggested that it is necessary to appreciate herdsmen as perhaps humanity’s earliest known tourists. But he also contends that Nigeria’s herdsmen need to be convinced to appreciate that there is a culture of settlement in parts of the country. And they must learn to seek accommodation with settled hosts wherever they encounter them through mutual understanding of the need for each other and not through violent displacement of fellow Nigerians from their ancestral homes.

As a matter of fact, grazing routes were established in Nigeria many decades before the country became independent in the knowledge that cattle rearers compulsorily moved from place to place as it was their way of life. During such movements, they were able to graze their cattle. In those years in the 50s, government created grazing routes from the northern cattle supplying to the southern consuming regions of the country. They were not specific areas as such, but the nomads could identify the routes as they observed the previous movement of their cattle from one village to another. These herdsmen would travel through those tracks which were usually introduced to them by their parents. They would travel from one part of the country to another, grazing their cattle along those routes. But today, they cannot find those tracks anymore. The tracks have been covered as farmlands by farmers who say they need their land for their work.

That is the problem and for the cattle rearers, it is a serious problem. As they move from one village to another, they are faced with obstacles on their routes, mostly from cattle rustlers. For the cattle rearers, it is a disturbing situation. But more disturbing is the persistent violent clashes between the herdsmen and the farmers which in recent months have taken unprecedented tolls in human and material resources. The north, the middle belt and parts of the south have continued to witness frequent clashes as herders claim their cattle had either been stolen or killed, or that their men had been attacked and killed and they had embarked on a reprisal mission, killing farmers in their hundreds and setting their houses on fire.

One point to consider is that since the 1950s when grazing routes were created in Nigeria, the population of the country has grown from 30 million to almost 200 million. This massive increase in population has inevitably put enormous pressure on land and water resources used by both farmers and herdsmen. One of the results of this development is the loss of grazing land to agricultural expansion. This has led to an increased southward movement of herdsmen which, in turn, has led to increased conflict with local communities, especially in Plateau, Kaduna, Niger, Nassarawa, Benue, Taraba and Adamawa States involving Fulani herdsmen and local farmers. But of greater concern still is the fact that the violence between herdsmen and farmers has developed into criminality and rural banditry. And this is the main challenge that is currently starring the Nigerian government rudely in the face. That is the development that the Nigerian government should be more committed to eradicating.

So, again, it is unfair to accuse Gowon of creating grazing routes to herdsmen, wherever they come from, in order to supply Nigeria with mercenary fighters to help his government prosecute the Nigerian civil war. That was definitely not the case because those routes had been there even before Nigeria attained self rule. At the moment, Nigeria has a total of 417 grazing reserves out of which only about 113 were gazetted. This means that in short and medium term, many cattle must continue to practise seasonal migration between dry and wet season grazing areas and ultimately, there will continue to be the need for permanent settlement of cattle rearers.

There are different shades of opinion as to what the government should do to contain these frequent conflicts before they escalate into a full blown war. Most people from the south are of the opinion that cattle-rearing is not a part of government business. It is like any other animal husbandry business, like goat and pig farming or poultry and therefore should not attract direct government intervention. And if government must support cattle rearers directly with legislation, the same magnanimity should be extended to all other businesses that involve meat distribution in the country. Others are of the opinion that owners of cattle who are generally known to be rich should negotiate to buy or at least lease some acres of land from state governments and local land owners at subsidized costs. They should then plant and water grass there for the feeding of their cattle in a sort of mechanised agricultural outfit that would be thoroughly fenced with barbed wire to ward of cattle rustlers. The grasses could be imported or acquired locally, planted and nourished within the cattle farm complex and only those cattle due for sale can be taken out and transported by trailers or train services to their destination when they are due for sale.

The government set up a peace committee which included Professor Ibrahim Gambari, former Chief of Army Staff, General Martin Luther Agwai, Human Rights activist, Professor Jibrin Ibrahim, former Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Professor Attahiru Jega, Dr. Chris Kwaja, Ambassador Fatima Balla, Dr. Nguyan Fesse, Mrs Aisha Muhammed-Oyebode and Mallam Y.Z. Ya’u to look into ways and means of containing the herdsmen-farmers conflicts that were consistently ravaging northern Nigeria.

In a memo submitted to President Muhammadu Buhari they explored the roots of the crisis and identified possible solutions. According to Professor Jibril Ibrahim, the memo titled “Pastoralist-Farmers Conflicts and the Search for Peaceful Resolution” aimed at finding a holistic solution to the challenge which was attributed to a variety of factors such as growth in population, failure of the old northern region to gazette demarcated grazing reserves, failure of current laws made to arrest the situation and the politicisation of issues. The committee noted that a holistic approach which would include a grand meeting of all stakeholders should be able to solve the problem of unnecessary conflicts between herdsmen and farmers.

However, in some areas, attacks have also had religious and ethnic undertones. In Plateau State, for instance the Berom indigenous farming communities are largely Christian, while the Fulani are overwhelmingly Muslim. The conflict between Christian farming communities and Fulani herdsmen in the area has been a recurrent decimal in the history of Nigeria. In August 2014, for instance, Alingani village, in Nasarawa State was completely destroyed by farmers with the support of the local Ombatse militia who belong to the Eggon ethnic group. On that fateful day in Alingani, fighting broke out when an Eggon farmer allegedly accused one herdsman of grazing animals on his land. “Everything belongs to Allah. Every piece of land belongs to Allah and not you,” the herdsman was said to have told the farmer. The argument that followed soon degenerated into a fight.

According to the police, 60 people were killed and more than 80 houses and properties were destroyed. In trying to flee the violence, eleven children aged ten and under drowned in the nearby Guyaka River. Elderly men and women as well as children were burnt within their huts. Only those children who went out grazing with animals survived.

In a retaliatory attack soon after, carried out by Fulani herdsmen against settled farmers, the herdsmen seemingly came from nowhere and started shooting guns. People had to run among their scattered cattle, which were running in different directions because of the shooting. That same night, Fulani mercenaries armed with automatic weapons invaded the village. They killed many. The local authorities failed to prevent the attack or arrest the perpetrators.

A typical danger that constantly faces the herdsmen is the attack that takes place along grazing routes at the hands of cattle rustlers and farming communities. But neither the long distances they walk, nor the dangers they are likely to encounter along the routes, have stopped them from their traditional way of life. Herdsmen still guard their cattle carefully and fight anybody who tries to harm them. They are well-armed. They move around with sticks, daggers and cutlasses, bows and arrows, swords and these days with AK 47 rifles and similar weapons to protect themselves against attack. In the process, many Nigerians have come to see them as a dangerous sect within the country. They have been known to forcefully occupy farmlands, sacking the legitimate owners and in some cases raping women in their farms and generally causing all manner of havoc on rural farming communities. The government is still trying to grapple with their perceived menace. But the question remains: in all these issues, where did General Gowon come in for blame?

- Asinugo is a London-based journalist and publisher of Imo State Business Link Magazine (imostateblm.com)