The Exportation And Importation Of Ruling Monarchs Between Yorubaland And Benin

Both Yorubaland and Benin have had a very rich history of exporting and importing between themselves ruling royal monarchs. The animated discussions on the Isale Eko monarchical heritage and its historical origins brings into sharper focus this historical phenomenon.

Ile-Ife accounts for the earliest documented historical account of such an export in relation to the very first Ogiso of Igodomigodo. That Ogiso and many of his immediate relatives were strangers to Igodomigodo and were Yoruba migrants from Ile Ife. This account has been documented by (a) P.R Page (in a book titled “Benin Arts and Crafts, Farm and Forest” page 166 and written in 1944), (b) M. Jungwirth (in a book titled “Gedanken zu einer Ethnohistorie des Benin Reiches” written in 1968 pages 68) and (c) P.A Talbot (in a book titled “The Peoples of Southern Nigeria. A Sketch of their History, Ethnology and Languages” written and published in London in 1926).

Curiously, an influential section of the people of Igodomigodo again turned to Ile-Ife during the time of acute political instability that characterized the brief time that Benin operated a republican system of government (otherwise termed the interregnum between the Ogiso and the Oba Dynasty). Jacob Egharevba’s book titled “a short history of Benin” was the first documented account, and an authoritative book, on Benin history (having discussed extensively with members of the royal court in the 1920’s and 1930’s as well as having discussed Benin history extensively with both Oba Eweka II and Oba Akenzua II)). He stated the events of that period thus:

“When Evian was stricken by old age, he nominated his eldest son, Ogiemwen as his successor, but the people refused him. They said he was not the Ogiso and they could not accept his son as his successor because, as he himself knew, it had been arranged to set up a republican form of government. This he was now selfishly trying to alter. While this was still in dispute, the people indignantly sent an ambassador to Ooni Oduduwa, the great and wisest ruler of Ife, asking him to send one of his sons to be their ruler, for things were getting from bad to worse and the people saw that there was need for a capable ruler”.

Even at that, Oba Oranmiyan and his two other subsequent successor Obas’ of Benin where condemned to rule from Usama as opposed to Benin city (as the powerful Ogiamien never quite completely ceded control of Benin city to the new dynasty). Jacob Egharevba states that it was only during the reign of the fourth Oba of Benin (Oba Ewedo) that the Oba dynasty established and consolidated control over Benin City itself.

However such control over Benin City was purchased (or should I say leased) for the duration of each successive reign of a given Oba of Benin (as the new Oba of Benin (and every successive Oba of Benin thereafter) is required, as part of the coronation ritual, to purchase the Ogiamien’s sand during his coronation thereby acknowledging his own external origin and affirming the land ownership as the birthright of the indigenous inhabitants). (per J. Nevadomsky in his book titled “Kingship Succession Rituals in Benin, III, The Coronation of the Oba” African Arts 17/3 (1984) page 56).

Similarly, parts of Yorubaland have imported ruling monarchs from Benin. Ashipa was the first regent of Isale Eko and representative of the Benin ruling family. The Indigenous Awori people caved into the threat of attack from superior military power of Benin Kingdom. Ashipa’s child (Ologun Ado) became his successor and the first Eleko of Eko (now referred to as “the Oba of Lagos”). Ologun Ado was succeeded (in succession) by his two sons Gabarro and Akinsemoyin. Oba Akinsemoyin was succeeded by his nephew (and son of his sister Erelu Kuti and Alaagba (an Ijesha Babalawo)) Ologun Kutere. Lagos Island or Isale Eko became a tributary state of Benin Kingdom for some time until the mid 18th century.

Interestingly enough, Benin Kingdom was itself was a semi autonomous part of and tributary to Oyo Empire. Rev Samuel Johnson in his book “The History of the Yoruba” written in 1897 and published in 1921 wrote:

“Sango was the fourth King of the Yorubas, and was deified by his friends after his death. Sango ruled over all the Yorubas including Benin, the Popos and Dahomey. For the worship of him has continued in all these countries to this day.”

The Rev Johnson’s accounts have been replicated in Walter Rodner’s book written in 1973 and titled “How Europe under-developed Africa”. Walter Rodner says on page 178:

“Indeed, although the nucleus of the Oyo Kingdom had already been established in the 15th Century, it was during the next three centuries that it expanded to take control of most of what was later termed Western Nigeria, large zones north of the river Niger and the whole of what is now Dahomey”

A view corroborated by the Encyclopaedia Britannica accounts of Shango worship.

Britannica (https[://]www[.]britannica[.]com/topic/Shango) states thus:

"Shango’s followers eventually succeeded in securing a place for their cult in the religious and political system of Oyo, and the Shango cult eventually became integral to the installation of Oyo’s kings. It spread widely when Oyo became the centre of an expansive empire dominating most of the other Yoruba kingdoms as well as the Edo and the Fon, both of whom incorporated Shango worship into their religions and continued his cult even after they ceased being under Oyo’s control."

Though Rev Samuel Johnson was quick to note (in his referenced book) that:

“the entire Yoruba country has never been thoroughly organized into one complete government in a modern sense. The System that prevails is that known as the Feudal, the remoter portions have always lived more or less in a state of semi-independence, whilst loosely acknowledging an over-lord. The King of Benin was one of the first to be independent of the central government, and was even better known to foreigners who frequented his ports in early times, and who knew nothing of his over-lord in the then unexplored and unknown interior.”

It must be said that post 1965 a new narrative started to gain some traction within Benin itself. That account was given major impetus by the book of the immediate past Oba of Benin. The new narrative resolved around a lost prince deemed to the only son of Ogiso Owodo who was said to have appeared in Ife as Oduduwa. It gained greater traction when the immediate past Ooni of ife failed to distinguish between the mythical origins of Oduduwa consistent with Ifa theology and spirituality and the actual origins of the man both of which were addressed and by Rev Johnson in his book “the history of the Yoruba”. The Yoruba word of mouth account of the origins of Oduduwa (the man) was stated by Rev Johnson thus:

"The Yorubas are said to have sprung from Lamurudu one of the kings of Mecca whose offspring were : — Oduduwa, the ancestor of the Yorubas, the Kings of Gogobiri and of the Kukawa, two tribes in the Hausa country. It is worthy of remark that these two nations, notwithstanding the lapse of time since their separa- tion and in spite of the distance from each other of their respective localities, still have the same distinctive tribal marks on their faces, and Yoruba travellers are free amongst them and vice versa each recognising each other as of one blood."

"The Princes who became Kings of Gogobiri and of the Kukawa went westwards and Oduduwa eastwards. The latter travelled 90 days from Mecca, and after wandering about finally settled down at He Ifg where he met with Agb^-niregun (or Setilu) the founder of the Ifa worship. "

Over time, however, less specific reference was made of the Mecca origins of Oduduwa in Yoruba folklore and more reference was made to the shorthand version of Oduduwa coming from the East. This undoubtedly provided the opening required by post 1965 revisionists to insert the lost Benin prince account into the narrative and give it plausibility (especially as Benin is technically to the East of Ife). This represents one the most acute dangers of word of mouth accounts which one cannot altogether exclude from having also occurred in relation to other now settled historical facts. This version failed because it was never alluded to by the current Oba of Benin’s grand father and great grand father nor any of the then senior members of the royal court of Benin (all of whom were interviewed in the 1920’s and 1930’s by Jacob Egharevba when compiling material for his, and Benin’s first, documented and most authoritative account on Benin history as written in his book titled “a short history of Benin”).

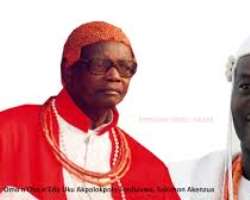

The new revisionist account cannot be unconnected with the political issues of that time. Oba Akenzua (in the early 60’s) led the way in agitating for a separate mid western region for minorities to be carved out of the then Yoruba dominated Western region. At that time, minorities of all three then existing regions complained (to different degrees) of acute marginalization and exploitation by the majority tribes within the respective regions. By that time, Benin had decided to chart an independent course for themselves within the political entity called Nigeria.

Be that as it may, both Benin and the Yoruba have a rich history of interconnection from a cultural and a monarchical perspective. Both have imported and exported to the other monarchical ruling families (many of whom over centuries have become biologically embedded to the localities over which they now rule).