IPOB & OHANEZE: BEFORE THE DAWN OF REALITY

I didn’t initially want to chronicle this. But after my friend, Comrade Aloysius Emeka Attah alerted the nation to the fact that Anambra State was pregnant and that it was pretty uncertain what kind of baby it was going to deliver of, I decided to chip in a few memories of what I know actually transpired in those days immediately after Nigeria had self rule, and how much all that has impacted and is likely to impact on the goings-on today.

In so doing, it is my hope that the young men and women in Nigeria who have been agitating for the resuscitation of the Biafra nation will be able make an informed decision on what they sincerely believe would be the best recourse for the Igbo as a people, given their current dilemma in Anambra State, and indeed in Nigeria.

This revelation becomes even more poignant when it is recalled that all the truth about what led to hostilities in Nigeria that ultimately led to civil war has never been told in its entirety. It is doubtful if the narrative can ever be exhausted. But like the history of every other people, talking or writing about the Nigeria-Biafra war would be like watching a masquerade display in a village arena. The way you see the events will depend on your angle of elevation or your location.

Even as we speak, most Nigerians either do not have a critical knowledge of the overt and covert events that led to that war or they decided, for whatever reason, to become economical with the facts. And yet, we know that there is nothing as more dangerous or more damaging as for a person who should be knowledgeable to keep groping in the dark about a situation or a condition he or she is most passionate about.

I was 20 years old when the Nigeria-Biafra war erupted. I was in the first year of my advanced level studies. So, I was quite able to understand and grapple with what was going on at the time.

I recollect that when the British ruled Nigeria as its colony, our people had absolutely nothing to worry about. There was constant electricity in the cities. There was water in the taps in the cities. Streams and rivers were there in the rural areas to contain the domestic needs of people who drank water or used it to cook, wash clothes and kitchen utensils or to bathe. The roads in every nook and cranny of the country were maintained on daily basis. There was the Public Works Department (PWD) which undertook the repair of all the roads from rural agricultural producing to urban consuming areas. Students and non-employed youths within the catchment areas of local councils were deployed to scoop sand and stones to fill in ditches on our roads on daily basis. And they were paid daily. So, there was daily employment for Nigerian youths who wanted to get some money to spend on a daily basis. In short, the infrastructure Nigerians needed at the time was largely available for their use. Nigerians never complained because there was just no reason for it.

By 1957, the wind of the quest for self rule among West African nations had begun to blow its way into Nigeria from Ghana. Nigerians watched Ghanaians secure and celebrate their independence that year. The sheer pride and happiness that engulfed Ghana motivated Nigerian politicians to double their efforts and put more pressure on the British government to grant the country self rule. Eventually, independence for Nigeria came in 1960. Three regions made up the country and they were the Eastern Region, the Northern Region and the Western Region. A fourth region, the Mid-West, was later added.

Nigerian politicians managed the country. Political alliances were forged. But just two years into Nigerian independence, trouble started. The crisis that erupted between Chief Obafemi Awolowo, leader of the Action Group Party and Chief Samuel Akintola who was also in the party led to the 1962 State of Emergency in Western Region. It is well documented and has become part of the dark spots in the country’s history.

Many Nigerians knew that the disagreement that erupted during the annual congress of the Action Group in Jos, Northern Nigeria on 2 February 1962 was not a sudden event. The misunderstanding was not like it was goaded by the spur of the moment instincts of the state actors. It had been building up, gradually but steadily, soon after Nigeria was granted self rule by the British. It was the political battle that laid the foundation of all other battles that have continued to bedevil the entire Nigerian political horizon ever since.

When the British left, even the army felt liberated. The political alliances in the country and even the army formation at the time were normal people who were

always eager to manifest their new-found strengths and relevance in the new dispensation.

Within the political parties, there were personal ambitions on the part of the politicians which led to scheming and manipulations. There was a desire to consummate those ambitions expeditiously, which led to impatience. There was the fact that not many of the politicians thought that building up a nation would take time and patience. There was insensitivity on the part of the politicians flouting their wealth and big new cars in public which was not a part of the British legacy and which attracted public disgust. And so, idealism came in conflict with realism.

In both the army and the political circles, there was courage and there was cowardice that culminated in betrayals. There was intellectual leadership and there was financial leadership, both attracting their followers. There was hate and there was love, sometimes manifest and at other times covert. There was magnanimity and there was pettiness that fanned self aggrandisement on the part of the political class. And so, there was trust and there was mutual suspicion within the polity.

The deteriorating political situation in the West had far reaching effects. One of those effects was that it gave rise to a new dimension in the vision of the khaki boys in the Nigerian Army. In that chaos, Igbo boys in the Nigerian army saw both a loophole and a possibility. And they began to nurse the ambition of the Igbo being the ones who should step into the shoes of the British colonial masters, now that they had left. Majors Kaduna Nzeogwu and Emmanuel Ifeajuna who masterminded the first coup that unseated the First Republic were both Igbo who grew up in the Northern Region. They knew the terrain and the relationships between the Easterners and the Northerners very well.

For the records, it is important to note that these army boys were very decent about their ambition. They meant to maintain the standards the country inherited from the British – the civil service, the banks, the agricultural enterprises, the roads and other infrastructure and if possible, improve upon them for Nigerians.

Their ambition was nursed by the fact that throughout the country at that time, the Igbo were the ones occupying all the viable positions in the country just the same way as Asians are doing in contemporary United Kingdom. They were there in the banks as workers and managers. They were there in schools as students and teachers. They were there in the markets as business men and women. They were there in the civil service as staff and permanent secretaries. They were there in the transportation industry. They were there in the hospitality industry. In Lagos, Ibadan, Kano, Kaduna, wherever you went, the Igbo practically dominated the national economy. And for that reason, the Igbo

boys in the army convinced themselves that only the Igbo could conveniently step into the shoes of the British and rule Nigeria with equity and the fear of God. And they became committed to this objective.

However, the objective was a sort of internal arrangement. They couldn’t possibly disclose this to those non-Igbo colleagues of theirs with whom they planned to embark on the first coup de tat Nigeria was to experience. It was their internal arrangement which no outsider was to know about. But they still had to enlist the support of their military colleagues. And together they sacked the government of President Nnamdi Azikiwe and Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa thereby redirecting the political and military focus of the country.

In the North, key political actors like the Saduarna of Sokoto, Sir Ahmadu Bello and the first Nigerian Prime Minister, Alhaji Tafawa Balewa were murdered in the coup. In the West, some key actors like Chief Samuel Akintola and Chief Festus Okotie Eboh, the Minister of Finance were also killed. But in the East, principal actors like Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe, Dr Akanu Ibiam and Dr Michael Okpara who the coup plotters had slated for death were not seen at home when the army boys went for the operation. It was strongly suspected that the plan had been leaked to them. So, not one Igbo leader was touched during that first coup.

This situation could have corroborated the internal plan of the Igbo military officers to get the Igbo to step into the shoes of the white man who was now gone. They saw that the cap fitted and were eager to wear it. So, the highest ranking army officer, Major General Aguiyi Ironsi was installed Head of State after the coup. Ironsi was an Igbo, from Umuahia. But the plan back-fired after those they executed the coup with now had an afterthought. Not one Igbo leader was killed during the coup. It was then construed that it was an Igbo coup and the Northerners staged a counter-coup.

Subsequent coups that culminated in the unstable position Nigeria finds itself at this time manifested all the threats we have already noted: courage and cowardice, betrayals, scheming and manipulations, mutual trust and mutual suspicions, and so on. All these led to distrust, the killing of Easterners in the North and the subsequent declaration of Biafra by the Igbo and the war that followed. But on January 15, 1970, Biafra surrendered.

Now, we need to do a little bit of reflection and ask ourselves some pertinent questions. For instance: was it a mere coincidence that the first coup was staged by Igbo majors Nzeogwu and Ifeajuna on 15 January and despite everything that happened, the genocide and the war, Biafra surrendered and the war ended on January 15? Was January 15 mere coincidence or was the hand of God in all of this?

That notwithstanding, there were several reasons why the Igbo could not secure Biafra at that time. First was diplomatic empathy. Many countries that had the colonial experience were on the side of the British who did not want to see Nigeria torn apart so soon after they had self rule. Except for her traditional rival, France, which recognised Biafra, most other countries in Europe and America were on the side of Britain and refused to recognise Biafra. They refused to sell arms to Biafra. So, while many Igbo were willing to fight for their liberation, they didn’t have enough arms and ammunition to prosecute the war. The atmosphere now is quite different because the leader of the IPOB has succeeded in creating a wider awareness globally about the desire to resuscitate Biafra. That is important in the Igbo struggle for self determination and every Igbo should readily credit Nnamdi Kanu with that success.

There was the disagreement between Ojukwu and the Chinese government which offered to fight and win the war for Biafrans if the crude oil in Biafra would be leased to China for 99 years. Ojukwu felt that 99 years was such a long time to commit the destiny of a people. Had he realised that none of the people who would have signed the agreement would live for 99 years and that at some point, when those who signed the original agreement would have given way, a new government could decide to nationalize all the oil in the country. And had Ojukwu, given this knowledge, agreed to sign the document asking the Chinese to fight for Biafra, the story would have been a far cry from what it is today.

Despite all that, Biafrans at a point were advancing towards Nigeria. They were taking the battle into Nigerian land. But half way, Banjo betrayed the Biafran course and reversed all the gains the Biafran troops recorded. He paid for that betrayal with his life. Coupled with that was Ojukwu’s refusal to bomb civilian populations. While Nigeria was doing everything to frustrate Biafra, bombing schools, markets, churches and wherever there was a concentration of civilians, Ojukwu refused the advice to bomb big markets in Lagos like Alaba, Idumota, Oshodi, Onyingbo or Mile 12. If he had done so, the Western Region would have given up their romance with the North, allowed Biafrans to go and possibly declared Oduduwa Republic. But being a British-trained Igbo, Ojukwu insisted on fighting the war with the military ethic that was globally recognized as best practice. He refused to bomb civilian populations in Nigeria in retaliation.

The last straw that broke the camel’s back was when Ojukwu had a misunderstanding with Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe. Following that rift, Dr Azikiwe defected from Biafra to Nigeria. And that was it. Our people say that the man who does not know where the rain started beating him will never know where he dried his body. A few days after the defection of Dr Azikiwe to Nigeria, we were in the forward location fighting. I was at the Oguta sector. Then signals

went out all through Biafra land that the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) had raised a massive army that was marching down on us. We thought: if we were unable to beat Nigeria, how could we possibly face the OAU? In our state of exhaustion, no one remembered that the OAU didn’t even have an army. All of us, soldiers, dropped our guns, some at the forward location, and headed for our various homes. Biafra collapsed. Biafrans were tricked into surrender by one old and wise man who felt unduly humiliated by the words the Biafran leader said about him. He accepted those words as a challenge to prove his superiority. And again, the course of history in Nigeria was redirected.

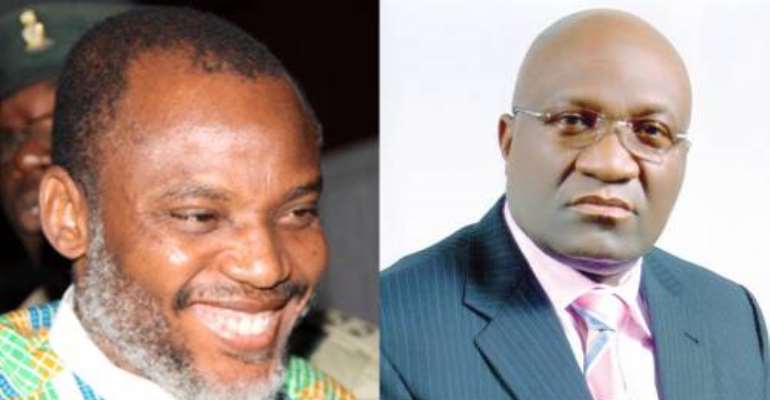

Yes. History repeats itself. But this time I am sure that Igbo leaders can avert this vicious repetition if the hand of God is truly with them. One would have thought that with the current arms twisting between the leaderships of IPOB and Ohaneze, lessons would have been learnt from our past experiences in Nigeria. But it doesn’t seem that any lessons have been learnt. For one thing, the success of the 30 May sit-home injunction was firstly because most Igbo are sentimentally attached to that date: the day the Republic of Biafra was declared. Another reason was that business men and women were afraid that hoodlums would raid and loot their shops if they opened them on that day.

The scenario in the case of the Anambra gubernatorial election is quite different. Even if the Igbo refuse to vote on 12 November, it will have no impact whatsoever on the status quo in Nigeria. Only Anambra people will suffer the consequences because the action will either prolong the stay of the incumbent governor unconstitutionally, or the federal government will capitalise on that situation to declare a state of emergency in Anambra State, or Anambra state will stay without a governor. Whichever way the pendulum swings, it is only the people of Anambra state who will bear the brunt.

A more meaningful and effective strategy would have been for the Igbo to plan to boycott the presidential election in 2019. Should that happen, it could be difficult for a president to emerge in Nigeria given the constitutional requirement that such a candidate must secure at least 25% of votes in not less than 24 states (two-thirds) of the country’s 36 states. And should that happen, perhaps the federal government will begin to reverse its position and begin to reconsider restructuring of the country by dispensing with tribal leadership altogether or officially giving tribes autonomy. That will not necessarily mean the death of Nigeria. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

Sadly, I have watched video clips of both Nnamdi Kanu and other young people using abusive languages on elders of Igbo land. And I hope that after what they now know, they will speak in public with some respect for their elders. Today, Mazi Kanu is consummated with the quest for Biafra. What if tomorrow his son disagrees with him because the younger man thinks the world is shrinking into a

global village and as such all Africa must come together to form a United States of Africa? Just in case that happens and the younger Kanu tells his father he is an idiot because he does not see that the world is turning into a global village, how would the senior Kanu feel? Please, my people, there is reason for caution in public utterances and there is reason to handle the Igbo issue with a sense of maturity. We must learn to confide in us and not wash our linen in public.

It reminds me of those days we were in the thick of battle at the Aba sector. One of our regimental police boys decided to take a risk to go over to the Nigerian side. We wanted to know who we were actually fighting. The boy stayed four days in the enemy camp and we thought they had killed him. But on the night of the fourth day, he came back to our rendezvous. The Nigerians had kitted him with a new camouflage uniform, a new beret, new boots and some money. They told him to tell us we need to come together and see who we were fighting. So, they mapped out a rendezvous half way between their location and ours. And here we met and drank beer and ate rice – things we had no access to in Biafra. But no guns were allowed. You had to drop your gun at the base if you were to enjoy the get together.

We were all young men between the ages of 17 and 26. And we began to ask ourselves questions: why are we young people fighting and killing each other while General Gowon and General Ojukwu who caused the war were in the comfort zones of their homes drinking tea and enjoying the company of their wives and children? Ojukwu was told that we compromised with the enemy, and on the 9th night, we were moved from the Aba sector to Owerri at midnight.

That was how I left the second battalion of ‘S’ Division and was redeployed in 48 battalion of 14 Division of the Biafran Army. It was here that we were tricked into believing that the OAU was invading us and we were all scared and we all dropped our guns and headed for our various villages and homes. Who would have thought that the OAU had no standing army?

Today, my friend Aloysius Emeka Attah has alerted us to the pregnancy of Anambra State. 12 November is still a few weeks away, enough time for the leaderships of Ohaneze and IPOB to make amends, and to speak to the Nigeria and the world as a people with one voice. This, they need to do before our dawn rudely awakens us and the rest of Nigeria and the world to our reality, the truth of who we can be as Igbo nation!