SICKLE CELL: EARLY DIAGNOSIS CAN INCREASE LIFE EXPECTANCY

Sickle cell

Medical experts lament that though over 40 million Nigerians are carriers of the sickle cell disorder, governments at all levels are yet to see it as a disease that requires public health action, reports BUKOLA ADEBAYO.

Hers was a sad end to a life of struggle with ill health.

After the 20-year old Ms. Abimbola Egunjobi completed her secondary school in Nigeria, she enrolled for the Advanced Levels programme in a London school. Considering the numerous crises she had had to grapple with as a sickle cell anaemia patient, everyone thought the worst was over as she marked her second decade alive. But, as is usually the case with most sickle cell anaemia patients, she paid the ultimate price on February 5, 2003, leaving her parents and siblings to mourn their indescribable loss.

A roommate of hers in school was so disturbed by the news of her death that she vowed never to marry an individual with even an AS genotype!

The idea, said the roommate, was to make sure that no one ever goes through the many crises her friend passed through while her short life lasted.

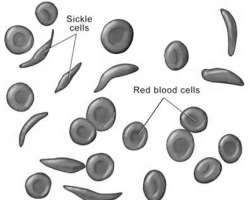

According to medical experts, Sickle-Cell Disease, or Sickle-Cell Anaemia (SCD or SCA) or drepanocytosis, is a genetic blood disorder characterised by red blood cells that assume an abnormal, rigid, sickle shape. Sickling decreases the cells' flexibility and results in a risk of various complications. The sickling occurs because of a mutation in the haemoglobin gene.

The term 'disease' is applied because the inherited abnormality causes a pathological condition that can lead to death and severe complications. Indeed, in sickle cell, life expectancy is shortened, with studies reporting an average life expectancy of 42 in males and 48 in females.

Sickle cell anaemia is a serious disease in which the body makes sickle-shaped red blood cells. In other words, the red blood cells are shaped like a 'C,' while the normal red blood cells are disc-shaped and look like doughnuts without holes in the centre.

Normal blood cells move easily through the blood vessels. Red blood cells contain the protein hemoglobin. This iron-rich protein gives blood its red color and carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

On the other hand, sickle cells contain abnormal hemoglobin that causes the cells to have a sickle shape. Sickle-shaped cells don't move easily through the blood vessels; they are stiff and sticky and tend to form clumps and get stuck in the blood vessels.

The clumps of sickle cells block blood flow in the blood vessels that lead to the limbs and organs. Blocked blood vessels can cause pain, serious infections and organ damage.

Sickle cell anaemia is one type of anaemia, which is a condition in which the blood has a lower than normal number of red blood cells. This condition also can occur if the red blood cells don't have enough hemoglobin.

Red blood cells are made in the spongy marrow inside the large bones of the body. Bone marrow is always making new red blood cells to replace old ones. Normal red blood cells last about 120 days in the bloodstream and then die. They carry oxygen and remove carbon dioxide (a waste product) from the body.

In sickle cell anaemia, a lower-than-normal number of red blood cells occurs because sickle cells don't last very long. Sickle cells usually die after only about 10 to 20 days. The bone marrow can't make new red blood cells fast enough to replace the dying ones, hence the crises usually experienced by sufferers.

Sickle cell anaemia is an inherited, lifelong disease. People who have the disease are born with it. They inherit two copies of the sickle cell gene—one from each parent.

People who inherit a sickle cell gene from one parent and a normal gene from the other parent have a condition called sickle cell trait, which is different from sickle cell anaemia. People who have sickle cell trait don't have the disease, but they have one of the genes that cause it. Like people who have sickle cell anaemia, people who have sickle cell trait can pass the gene to their children.

According to the chairman of the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria, Prof. Olu Akinyanju, over 40 million Nigerians are carriers of the sickle cell gene. And as frightening as it is, statistics say, about 150,000 babies are born yearly with the sickle cell anaemia.

However, contrary to what used to obtain, Akinyanju said, sickle cell disease is no more a death sentence, as evidence has shown that affected persons can live normally and as long as possible.

Sickle cell anaemia varies from person to person, he said. 'While some people who have the disease have chronic (long-term) pain or fatigue (tiredness), with proper care and treatment, many people who have the disease can have improved quality of life and reasonable health much of the time,' he said.

He also said that due to adequate care, the average life expectancy of an American with SCD, which was seven in 1973, increased to 53 years in 2003, which is far higher than the average life expectancy of the population of healthy Nigerians, put at 43 years, all because America invested in research, training and treatment of the disease.

Speaking in the same vein, a Senior Medical Officer at the National Sickle Cell Centre, Idi-Araba, Lagos, Dr. Toriola Femi-Adebayo, said the government should adopt the policy of new-born screening for early diagnosis of sickle cell disorder. This, she said, would help to reduce some health complications.

Asked why private hospitals were not doing it, she said neo-natal screening was a capital intensive project that also required a multidisciplinary approach, which will only be beneficial to Nigerians if done in government-owned hospitals.

Femi-Adebayo said that though sickle cell anaemia was not yet regarded as a disease that required public health action from the government, there had been no foreign aid or grant to sponsor the schemes and treatment.

'It has to be a policy from the government. After screening, those with the disorder should be counselled by genetic counselors, and appropriate treatment initiated,' she explained.

Better still, Femi-Adebayo said, another major advantage of the screening was that it would ensure that statistics of babies born with the disorder in the hospitals are known and provisions can be made based on the figures provided.

In an effort to eradicate SCD, some religious organisations, especially the churches, hold counselling sessions for intending couples, while many advise their members to do medical tests to determine their genotypes before proceeding further in the relationships. This, they do, to stop marriages that would have been contracted by two people who are carriers of deadly diseases, including sickle cell.

Despite the lofty intentions behind this monitoring, some critics say the practice could cause stigmatisation of those affected, or lead to denial and falsification of genotype status by people living with sickle cell disorder or healthy carriers. All this, they argue, could be counterproductive to the efforts to manage the disorder in the country.

According to a genetic counsellor with the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria in Lagos, Mrs. Ayo Otaigbe, discouraging sickle cell carriers from getting married would not stop the incidence of children being born with sickle cell anaemia in Nigeria.

She said that as a genetic counsellor, she ensures that couples at risk are given accurate, full and unbiased information that offers guidance but allows them to make their own decisions.

She recommended pre-natal diagnosis for pregnant women at risk, where a sample of chorionic villus (placenta cell) is taken for test when pregnancy is about 11 weeks. 'The snag is that PND, for now, is expensive for most people that require it,' Otaigbe lamented.

'It is a very sensitive test, some equipment costs as much as millions of naira. It is also expensive abroad, but their governments have made provision for it,' she said. She explained that if PND shows that a foetus has sickle cell anaemia, couples could make informed decisions about the issue.

She said a PND test could help parents who would be having sickle cell children to garner medical information that would increase the life expectancy of the child.

One of the problems contributing to the complications of SCD is the management of the disorder. According to Otaigbe, parents of affected children only get to know the genotype of their kids at a later stage, especially after a major crisis. This, she said, could cause premature deaths in babies.

Otaigbe, who is also the president of Sickle Cell club in Nigeria called on the government to ensure that babies have their genotypes tests done, and SS children registered in sickle cell clinics for proper management.

Sickle cell sufferers and their parents are also encouraged to join sickle cell clubs where they can associate and learn more about the disorder.

'The genotype test should be made compulsory for all babies brought to the hospital. If we detect their status on time, we can treat them by referring them to the appropriate quarters. But how many hospitals in this country have sickle cell clinics?' she asked.