HIV/AIDS VACCINE SHOWS LONG-TERM PROTECTION AGAINST MULTIPLE EXPOSURES

USING human immune system cells in the lab, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) experts at Johns Hopkins, United States, have figured out a way to kill off latent forms of HIV that hide in infected T-cells long after antiretroviral therapy has successfully stalled viral replication to undetectable levels in blood tests.

In a report to be published in the journal Immunity online March 8, the Johns Hopkins team describes a vaccination strategy that boosts other immune system T-cells and prepares them to attack HIV, before readying the virus for eradication by reactivating it.

Also, an Atlanta, U.S., research collaboration may be one step closer to finding a vaccine that will provide long-lasting protection against repeated exposures to HIV. Scientists at Emory University and GeoVax Labs, Inc. developed a vaccine that has protected nonhuman primates against multiple exposures to simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) given in three clusters over more than three years. SIV is the nonhuman primate version of HIV.

The research was presented March 7 at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Seattle, Washington DC, U.S.

The vaccine regimen included a DNA prime vaccine that co-expressed HIV proteins and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). GM-CSF is a normal protein that promotes the initiation of immune responses and thus enhances the ability of the vaccine to elicit blocking antibodies for the SIV virus before it enters cells.

Vaccination consisted of two DNA inoculations at months zero and two to prime the vaccine response and then two booster inoculations at months four and six. The booster vaccine was MVA, an attenuated poxvirus expressing HIV proteins. Six months after the last vaccination, both vaccinated and unvaccinated animals were exposed to SIV through 12 weekly exposures, resulting in an 87 per cent per exposure efficacy and 70 per cent overall protection. Over the next two years uninfected animals were exposed multiple times in two more series, resulting in an 82 per cent per exposure efficacy during the second series and an 84 per cent per exposure efficacy during the third series.

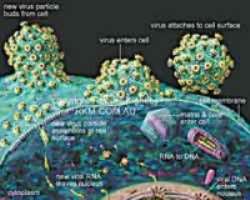

Meanwhile, HIV has long been known to persist in a dormant, inactive state inside immune system T cells even long after potent drugs have stopped the virus from making copies of itself to infect other cells. But once treatment is stopped or interrupted, the latent virus quickly reactivates, HIV disease progresses, and researchers say it has proven all but impossible to wipe out these pockets of infection.

Johns Hopkins senior study investigator and infectious disease specialist Prof. Robert Siliciano, who in 1995 first showed that reservoirs of dormant virus survived, says the resulting need for lifelong drug treatment has raised concerns about the adverse effects of decades of therapy, the growing risk of drug resistance, and the rising cost of care.

Siliciano and other AIDS scientists say the best hope for ultimately curing the disease is to force latent viruses to 'turn back on,' making them 'visible' to the immune system's so-called cytolytic 'killer' T-cells and then, with the likely aid of drugs, eliminate the infected cells from the body.

In his new study, Siliciano showed that infected T cells survived after latent virus was reactivated, and were only killed off when other immune system T-cells were primed before reactivation.

'Our study results strongly suggest that a vaccination to boost the immune response immediately prior to reactivating latent virus may be essential for totally eradicating HIV infection,' says Siliciano, a professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

In their journal report, Siliciano and his colleagues describe their vaccination strategy and how short pieces of HIV proteins were introduced to stimulate the anti-HIV T-cell response just before reactivation of the latent virus. The incomplete viral proteins and subsequent immune system vaccination led to production of enough cytolytic T-cells to attack and kill the latently infected cells.

Siliciano and his team next plans to test different methods for boosting the immune response before latent virus reactivation and compare their effectiveness in clearing all HIV- infected cells.

Currently, there are more than 34 million people in the world living with HIV, including an estimated 1,178,000 in the U.S. and four million in Nigeria.