TWO MATTERS OF STATE

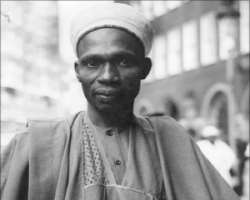

The Federal Government decided to name the newly-built, eight-storey Foreign Affairs Complex in Abuja FCT, after the late Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa on Monday, March 21, and the rationale was that Balewa was Nigeria’s first Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Indeed, many countries of the world name their Foreign Office buildings after the first Minister of Foreign or External Affairs, and so, Nigeria in following that tradition chose Balewa. I have issues with that. As former Prime Minister of Nigeria, and first leader of independent Nigeria, Balewa deserves recognition. But naming the Foreign Affairs Complex after him is one honour too many. There ought to be greater sensitivity in the naming of public buildings after living or dead public figures. There is so much lopsidedness in the approach adopted every time by the Federal Government, with the effect that certain historical personages have been honoured too many times whereas many, whose contributions have been just as impactful, or whose place in history is noteworthy, have been ignored. Prime Minister Balewa is one of such persons with more than a fair share of public monuments already named after him: others in this category will include Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Sir Ahmadu Bello and Mallam Aminu Kano to name the more prominent ones.

The real offence in this naming and branding process is the attempt, however, to play games with history or to be selectively amnesiac. Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa combined the position of Prime Minister with that of the Minister of Foreign Affairs between 1960 and 1961, and led the first Nigerian delegation to the United Nations in New York. But the first substantive Minister of Foreign Affairs was Dr. Jaja Nwachukwu. If the Federal Government wanted to name the Foreign Affairs Complex after the first Foreign Affairs Minister, it would have been more appropriate to honour Jaja Nwachukwu, not Balewa whose primary duty at the time was in fact that of Prime Minister. And Jaja Nwachukwu was no push-over nor was he an outsider in the foreign policy process of the First Republic. Between 1960 and 1961, he was Nigeria’s first Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations. He, it was, who hoisted Nigeria’s flag on its admission as the 99th member of the United Nations on October 7, 1960. Nwachukwu was an assertive, outspoken member of the United Nations family who cultivated many friends for Nigeria, and was known for his well-reasoned contributions.

In 1961, he returned to Nigeria as Minister of Foreign Affairs, in which capacity he equally acquitted himself honourably. Before all of this, Jaja Nwachukwu was the first Speaker of Nigeria’s House of Representatives (1959-1960); and Minister of Economic Development (1960). Subsequently, he served as Minister of Aviation (1965 -1966). In the Second Republic, he was elected twice (1979 and 1983) as the Senator representing Aba Senatorial zone, and at the Senate, he served as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Prime Minister Balewa, who was very fond of him, referred to him as “the bookish Minister.” Time magazine once described him as “the pride of Africa”. In September 2010, President Goodluck Jonathan honoured him post-humously, with a Golden Jubilee anniversary award in recognition of his contributions to the making of modern Nigeria. Why then was he denied the honour of having the Foreign Affairs Complex named after him? Amnesia? Politics?

If the Federal Government wanted to name the Foreign Affairs Complex after Balewa, they should just have done so instead of insisting that he is deserving of the honour because he was first Foreign Affairs Minister! It is worth noting that this is not the first time an attempt will be made to overlook key historical figures by the Federal authorities. Emmanuel Ifeajuna was the first black African to win a Commonwealth Games Gold (1954) but he is often conveniently ignored in official Nigerian history. He took part in the January 15, 1966 coup, yes, but should that automatically erase his history? The military authorities chose to name the Police Force Headquarters, then in Lagos after Kam Salem who was the second indigenous Inspector General of Police (1966- 1975). Louis O. Edet who was the first indigenous Inspector General of Police (1964 -1966) was denied that honour.

The grave error and injustice has now been corrected many years later with the naming of the Police Force Headquarters in Abuja after Louis Edet. And there are people in the corridors of power who would cleverly rationalize these omissions. Louis Edet, would have remained neglected were it not for years of sustained protest in the media. Hopefully, Jaja Nwachukwu, first Nigerian Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations and first substantive Minister of Foreign Affairs, will one day get the honour that he rightly deserves. To those who think otherwise, the following lines from the first stanza of the national anthem should be useful: “… the labour of our heroes past shall never be in vain/to serve with heart and might/One nation bound in freedom/ peace and unity.” Will anyone be encouraged “to serve with heart and might” with the state in the hands of revisionists?

The real question however is: how do we honour people? This is the same question with the annual National Honours awards. Honours should be used as symbol of values, and for excellence, and in recognition of concrete achievements in order to inspire others to serve, and not to play politics. It is obvious that the Federal Government has no serious template for managing processes and so there is no level playing field in these matters.

So it is as well with the legal framework for the April 2011 elections: I had written a piece a few weeks ago lamenting the fact that there has been no time limit placed on the adjudication of election petitions in the amended 1999 Constitution. This had resulted in the kind of untidy situation in which we now find ourselves whereby eight days to the 2011 general elections, there are still hundreds of election cases from the 2007 elections which are still before the courts; yet to be determined. With fresh elections due in many of the affected constituencies, and new candidates on the field, those unresolved cases would soon die a natural death; the basis of the justice that the petitioners seek having been overtaken by events, and the courts not likely to act in vain.

To go to a court of law and be denied justice under such circumstances amounts to injustice in itself, and this may serve as future incentive for self-help. Hence, both civil society and the Uwais committee on electoral reform had recommended that election cases be determined speedily before the inauguration of a new administration, also to eliminate the possibility of a wrong person occupying an office for so long before being dismissed by the courts as seen in Ondo, Ekiti, and Anambra. I argued that we had missed the opportunity to amend the 1999 Constitution accordingly. But not so, thought a reader.

He drew my attention to Section 285 of the amended 1999 Constitution. I checked my copy of the amended Constitution. The time limit for adjudication wasn’t there. In response to his insistence, I started collecting copies of the Nigerian Constitution, 1999 as amended and also the Electoral Act 2010 (with 2011 amendments). The best place to get a copy of these important documents is in the traffic, either in Lagos or Abuja. As the traffic crawls, you’d find street hawkers pushing all kinds of Nigerian law documents in your face, mostly decorated with the seal of the Federal Government of Nigeria, and clearly marked “Original” or “Corrected Original”. These copies are produced by roadside printers, and their objective is to make profit. This is what I discovered: some of the copies have different sections. I finally found Section 285 (5-8) in a version in circulation. Some versions are riddled with grammatical errors and serious omissions. The effect is that I ended up with three different copies each of the Electoral Act 2010 (with 2011 amendments) and the 1999 Constitution (amended), even when they all bear the same dates. I stumbled on yet another set at the Nigerian Bar Association President’s Consultative Dialogue on the April 2011 Elections at the Ladi Kwali Hall, Sheraton, Abuja on Tuesday, March 22. The friendly salesman told me, “these copies were produced by a lawyer.” I felt encouraged. But some of the sections in the documents are different from what is in other copies in circulation.

And I am not alone in making this discovery. At the NBA session in Abuja, Resident Electoral Commissioners who took part in the Dialogue confessed openly that they too do not know the exact copy of the Electoral Act that is meant to provide the legal framework for the 2011 elections. They were that honest! Even lawyers concurred that there is great confusion out there about the legal framework for the elections. So what are we doing then, going into an election, with so much ignorance and confusion about such an important framework? It is a sign of the weakness of the state that neither the National Assembly nor the Federal Ministry of Justice, or any other authorized official body has deemed it necessary to identify, publish, and circulate gazetted copies of the 1999 Constitution as amended and the Electoral Act 2010 (with 2011 amendments).

In the past, there used to be a body known as Government Printers which printed and circulated official documents. The version from the Government Printers could be taken to be the correct and true copy. But that once valuable department has since gone into oblivion. Government documents are now accessed from whatever source including the internet, and printed and sold on the streets by all manners of persons. We run the risk of a similarly great confusion in the law courts after the 2011 elections. But for now, it is bad enough that the legal framework for the elections is largely unknown, the voting procedure, announced ten days to the first election, is also just as unknown to the generality of the electorate who may not understand the difference between accreditation and actual voting. How we stumble!

The confusion is contrived. There was more than enough time between the 2007 and 2011 elections for the National Assembly to amend the Constitution and the Electoral Act and ensure general familiarity with and understanding of the main legal framework for the next elections. But the politicians deliberately delayed action and embarked on mischief. There was no enthusiasm in official corridors over the Uwais Committee report on Electoral Reform. The Joint Committee of the National Assembly on Constitution Amendment fought over who should be Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the body as if this mattered most. Today, we seem set to pay the price for the confusion that has been unleashed on Nigerians: we are going to the polls all the same, with political parties, voters, local and international observers, lawyers and the media clutching different versions of the enabling law and without a level playing field!

Written by Reuben Abati.