Harnessing Cultural Heritage For Tourism Development In Nigeria: A Study Of The Osun-osogbo Sacred Grove And Festival

INTRODUCTION

Tourism is one of the fast-growing sectors of the global economy. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (2019), reported that international tourist arrivals as of 2018 were 1.4 billion, while total export earnings from international tourism were projected to be USD 1.7 trillion, or almost USD 5 billion per day on average. In addition to this, the World Travel and Tourism in Oladeji and Olatuyi (2020), stated that tourism generated about 9 per cent of total GDP and provide more than 235 million jobs in 2010, representing 8 per cent of global employment. These facts explain the capacity of tourism to generate revenue for governments and private business entities operating in the sector across the globe. At the same time, the sector has created and continues to create huge employment opportunities for many skilled and unskilled labourers across the globe. To this end, several countries around the world are making a conscious effort to diversify their revenue sources through massive investment in tourism and tourism-related activities.

There is no nation without a culture that defines them as a people, and this culture is passed down from one generation to the other. Cultural heritage is an aspect of tourism with an increasing global appeal. According to Omisore, Ikpo, and Oseghale (2009), cultural properties are an important component of the environment, which may be viewed as religious festivals and natural topographical landscape sites in form of relief features (hills, mountains, valleys, rock, outcrops, streams, and rivers) that have been accorded significant historical and cultural relevance. Given this, Oladeji and Olatuyi (2020) saw cultural heritage as a fundamental aspect underpinning a country’s national identity and sovereignty which needs to be sustainably conserved and managed for economic, cultural, environmental, and social values.

The United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in recognition of the need to preserve cultural heritage for present and future use has over the years made effort to preserve certain historical sites and monuments across the world. From the report of the World Heritage Centre of UNESCO, there are 802 cultural World Heritage sites, and 197 are categorized as natural sites, 32 as mixed sites categorized as both natural and cultural sites (World Economic Forum, 2015). In addition, UNESCO established the World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme (WHSTP) to provide negotiation and collaboration among stakeholders in tourism planning and cultural heritage management at a destination level. World Heritage and Sustainable Tourism Programme (WHSTP) provides opportunities to value the natural and cultural assets, protect, and develop appropriate tourism mechanisms (Oladeji and Olatuyi, 2020).

Nigeria is endowed with a huge cultural heritage by the virtue of the multi-ethnic and linguistic nationalities that make up the country. Despite the rise in civilization and technological advancement, many indigenous people of Nigeria from different ethnolinguistic backgrounds still hold on to their cultural values, symbols, and practices and are making serious efforts to preserve such cultural values, symbols, and practices. These cultural heritages explain the origin, traditional beliefs, and religious practices of the indigenous societies in Nigeria. A cultural heritage that dates back centuries and has attracted the admiration of many within and outside Nigeria is the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove and Festival in Osun State, southwestern Nigeria.

Oseghale, Omisore, and Gbadegesin (2014) affirmed that Osun-Osogbo sacred groove is an organically evolved cultural and landscape site associated with the Yoruba traditional religion and culture. The annual religious commemoration known as the Osun-Osogbo Festival attracts tourists within and outside Nigeria could be a major source of income to the State government. Nijkamp and Riganti (2008) argued that cultural heritage can boost the local and national economy and create jobs by attracting tourists and investment, and providing leisure, recreation, and educational facilities.

Given the cultural significance of Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove and Festival not just to Osun State but Nigeria at large, the United Nation Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) on 15th July 2005, declared Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove a world heritage site (National Commission for Museums and Monuments, 2010). This decision by the international body was geared towards preserving the site from every form of illegal human activity.

There is no doubt that the potentials of tourism as a sector of the Nigerian economy remains largely untapped. This could be attributed to the lack of investment in the sector which has resulted in the lack of maintenance and conservation of tourism properties across the country. In line with this thought, Bismarck Rewane in Ajibola (2013) argued that Nigeria is among the countries of the world yet to commence nurturing its historical and anthropological assets to position them to become attractive. The Osun-Osogbo sacred groove and its annual religious festival could yield unprecedented revenue for both the government of Osun State and Nigeria if the historic site is properly conserved and managed as studies have revealed. Given this backdrop, this study examines the economic importance of Osun-Osogbo grove and festival, challenges to its conservation, and the appropriate solutions.

CONCEPTUAL REVIEW

Cultural Heritage

Irrespective of an individual’s preference, the term culture or heritage or cultural heritage means the same thing. However, no matter the choice of word, we refer to the traditional elements that define the origin, present, and future of a particular human community. For Ezenagu (2020), cultural heritage involves a demonstration of human development which includes all aspects of a community’s valued past and present passed on through generations. Ezenagu maintained that many a times heritage is considered from a cultural perspective because it is solely the product of human activities and that is why heritage resources, cultural resources, and or, cultural heritage resources are used interchangeably.

International Council on Monuments and Sites (1999) described cultural heritage as a people’s legacy “inheritance” from the past, what they live with today, and what they pass on to future generations. Cultural heritage incorporates landscapes, historic places, sites, and built environments, as well as biodiversity collections, past and continuing cultural practices, knowledge and living experiences (Günlü, Yağcı, and Pırnar, 2013). For Schaefer (2002), it is the entirety of learned, socially transmitted customs, knowledge, material objects, and behavior. Ezenagu (2014) opined that culture is a word that defines man’s relationship, communion, and adaptation to his environment, and in the process of environmental adaptation man changed products and processes: norms, folklores, dance, traditions, customs, religion, ceremonies, rituals, the arts, crafts, language, dress, food, architecture, and landscape.

United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (2003) defined cultural heritage as the present manifestations of the human past. According to UNESCO, these are typically those essentials of our past that possess the ability to input to our grasp and appreciation of human history or which are a significant part of unending cultural traditions in a spiritual and emotional sense. These essentials of our past are the creative genius of human activities on the environment invested with cultural significance in society and the buildup of these essentials and experiences from human creativity formed heritages which manifests as the priceless cultural traditions of the society (Ezenagu, 2020). Given this, the result of cultural traditions shaped objects and generated knowledge which actively produced palpable and impalpable historical legacies acknowledged today as cultural heritage (products of culture) (Ezenagu, 2017, 2015). In this situation, Weiler and Hall (1992) considered cultural heritage to be a significant economic instrument as well as a key tourist attraction.

Cultural Heritage Tourism

Cultural and Heritage Tourism Alliance (2002), affirmed that the term “cultural heritage tourism” is referred to some as cultural tourism, some heritage tourism, some cultural and heritage tourism. Irrespective of the chosen term, the fact of the matter is that there is no precise definition of the term. However, in a simple term, cultural heritage tourism could be seen as the interplay between cultural heritage and tourism. It can also be seen as the process of harnessing cultural practices and values to attract tourists who wish to see and experience them. For Yale (1991), cultural heritage tourism is concerned about what humans have inherited, which can mean anything from historic buildings to artworks, to the beautiful scenery that possesses cultural and tourism relevance. Also, to define cultural tourism, Leslie and Sigala (2005) see it as the segment of the tourism industry that places special emphasis on heritage and cultural attractions.

Given the above, Edgell (2006) affirmed that cultural heritage tourism is travel that is inspired entirely, or in part, by artistic, heritage, or historical attractions. Most often cultural heritage tourism is associated with the travel wish of persons to consume or learn about arts, humanities, museums, festivals, food, music, theatre, and special celebrations of a people which are the products of their cultural heritage. Hunziker and Krapf in Dewar (2005) stated that there is no tourism without culture. The need to gratify tourist interest to see other people in their true environment and to view the physical exhibition of their lives as expressed in arts and crafts, music, literature, food and drink, dance, play, handicrafts, language, and ritual gave birth to cultural heritage tourism (Dewar, 2005). Given this rising curiosity among tourists, Timothy and Nyaupane (2009), argued that people visiting cultural and historical resources is one of the largest, most pervasive, and fastest-growing sectors of the tourism industry in modern time. Therefore, since cultural and historic resources are fast becoming tourism desire for most people across the world, UNESCO World Heritage Centre has continued to promote tourism through the recognition of historic sites across the world to prevent the destruction of cultural processes and products embellished with many outstanding historic values through commodification such resources are listed as World Heritage Site (Ezenagu, 2020). The inclusion of Osun Osogbo sacred grove on the World Heritage List no doubt has made it a tourist attraction globally.

Nigeria’s Cultural Heritage

Nigeria is a nation with a rich and unique history and cultural heritage resources. These include historic places, landscapes, sites and built environments, biodiversity, collections through past and present traditions, cultural practices, indigenous knowledge, and technology to the contemporary life of the host communities (Ezenagu, 2020). These unique historical and cultural heritage resources of different communities in contemporary Nigeria have been declared national monuments by the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) the only state institution in Nigeria charged with the responsibility to declare cherished cultural products and practices national monuments, constitute the tourism potential and tourist appeal of the country.

According to Ezenagu (2020), the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), presently have declared 65 heritage properties national monument across the country because of their inherent values and outstanding significance beyond the community and states where they are located. Some of these unique heritage resources include Nok culture of Kaduna state, Argungu fishing festival of kebbi state, Masquerade (mmonwu) festival of Anambra state, the Great Kano Wall, Kano state, Dye Pits of kano state, Mbari Art of Imo state, Sukur kingdom, Osun Osogbo sacred grove, Esie stone sculptures, etc. These heritage resources are of great cultural significance to the country. So far, only two national heritage in Nigeria “Sukur Cultural landscape and Osun Osogbo sacred grove” have been recognized and added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Osun Sacred Grove

Sacred sites are places of spiritual importance to people and communities (Oviedo and Jeanrenaud, 2006). African communities are known to have natural sites which are considered sacred because of their religious and spiritual significance. The sacredness of certain places is usually attached to certain exceptional features within the natural environment not limited to rivers, rocks, mountains, caves, trees, and constructed buildings (Ezenagu and Iwuagwu, 2016). These sacred sites are believed to be the residence of deities, spirits, shrines dedicated to ancestors. One of these sacred sites in Nigeria is the “Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove”.

The Osun-Osogbo sacred grove is a large cultural site of unbroken forest along the banks of the Osun River with sanctuaries and shrines erected along its course. It is dedicated to Osun, the Yoruba goddess of fertility. The sacred grove which more than four centuries are the largest of the sacred groves that have survived to the present. According to National Commission for Museums and Monuments (2010), the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove is located on the border of the southern forests of Nigeria on an elevated plot which is about 350 meters above sea level. In the east, it is bounded by Osun State Agricultural Farm Settlements and in the North by Laro and Timehin Grammar Schools. On the South of the grove is the entrance of Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH) which runs parallel to form a western borderline.

Osun River. Source: Oseghale, Omisore and Gbadegesin (2014).

In the twentieth century, the movement of New Sacred Art led by Susanne Wenger (1915–2009), an artist and Yoruba priestess, restored efforts to protect the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove by adding modern sculpture to the spiritual significance of the grove. This movement transformed Osogbo into a center of artistic activity and new ideas about contemporary African art (Olawale and Orga, 2019). This contributed to Osun-Osogbo sacred grove being designated a World Heritage Site in 2005 by UNESCO.

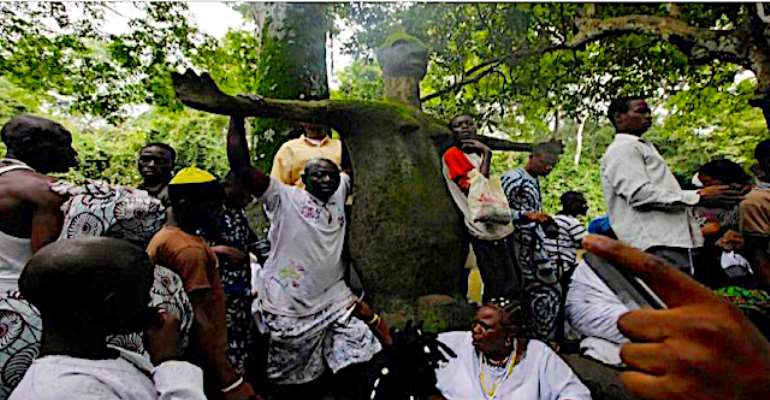

Worship points (shrines) at the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove. Oseghale, Omisore and Gbadegesin (2014

In time past, sacred groves used to be found in many Yoruba communities, but their sudden disappearance over time as a result of the negative attitude of man towards the environment has made Osun-Osogbo an important reference point for Yoruba identity. It is believed that the sacred grove is where Osogbo ancestors met the Osun goddess and they entered into a covenant sealed with an annual sacrifice that has been kept for many decades now (Ezenagu, 2020). This particular incident made the sacred grove a tangible expression of Yoruba divinatory and cosmological systems; its annual festival is a living, thriving, and evolving response to Yoruba beliefs in the bond between people, their ruler, and the Osun goddess (NCMM, 2004).

Osun Osogbo Festival

Osun-Osogbo festival is an annual event that revolves around the Ataoja and the Osogbo people. The cultural relevance of the festival cumulates in the people’s religious obligations to the goddess, Osun, who chose the sacred grove as her abode with evidence of her liquid body (Osun River) flowing therein (Ezenagu, 2020). It is the renewal of the spiritual covenant between Osun and other deities of the people (Orga, 2016). The Osun-Osogbo festival is a 12-day event that begins in the town palace of the Ataoja, beginning with (Iwopopo) the physical and ritual cleaning of the pilgrimage route from the palace in the center of the town (Gbaeme) to the grove by the royal priestess (Iya Osun) and the priest (Aworo) accompanying the household of the Oba with traditional chiefs, high Chiefs and other notables with dancing and singing (Orga, 2016).

The second to the fifth day of the Osun-Osogbo festival is the appearance of masquerades dedicated to ancestors as well as Sango, the Yoruba deity of thunder. The night of the 6th day of the festival is dedicated to Osanyin, a Yoruba deity responsible for healing through the knowledge of the use of herbs, and a sixteen-point lamp using palm oil soaked in cotton wicks is lighted from 7 pm to 7 am (Orga, 2016). The Ataoja, his wives, Ifa priest dances round the sixteen-point lamp three times to the admiration of a cross-section of the Osogbo people present at the palace grounds and the 7th day is dedicated to the Ifa (divination) priests who also dance around Osogbo town (Orga, 2016).

The 8th day includes athletic performances by personified deities likes Oya, one of the wives of Sango with who Osun was in good terms (Oya has a sacred area within the main grove) (Orga, 2016). On the 9th day, the Ataoja and his high chiefs pay respect to his in-laws in a procession that leads from one house to the other. The tenth day is the laying out of the crowns of the past and present Oba (King) for a rededication to Osun and to invoke the spirit of the ancestors of the Ataoja for a bestowal of blessing on Osogbo people. On this occasion, the chief’s priests and priestesses will prostrate before the crowns in salute to the royal ancestors. The occasion is followed by eating and drinking in the courtyard (Orga, 2016).

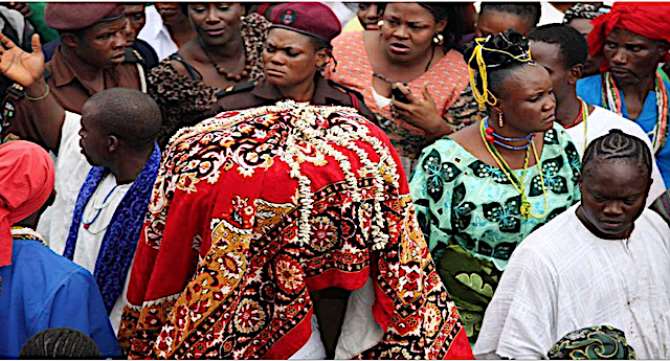

Worshippers at the annual Osun-Osogbo festival. Source: Chron in Okon (2018).

The 11th day is devoted to the final preparation for the grand finale that occurs on the 12th day. The people of Osogbo undertakes a procession which begins at about 9 am into the sacred grove and is led by the votary maid “Arugba”, who carries the ritual calabash of medicine and follows the ritual route to the Osun temple where she puts down the calabash in front of the Osun Priest, “Ataoja”, and devotes supported by high chiefs who accompanies her to the shrine. The procession which is accompanied by drumming, singing, and dancing covers the location of the first palace within the grove, the point of offering on the bank of the river. Among the main attraction of the procession is the flogging ceremony by youths of Osogbo which is done with flexible twigs of plants to the admiration of the Oba and all spectators. The flogging stops when the Oba (King) gives out money to the youths. Another star attraction is the display of various Egungun (ancestral) masquerades.

Worshipers of the Osun goddess make their way along with an unidentified virgin girl 'Arugba', center, to the river in Osogbo, Nigeria. Source: Chron in Okon (2018)

On the arrival of the votary maid (Arugba) to the shrine, there are loud ovations with the beating of drums and dancing. The Ataoja is then called into the temple where he sits on the stone throne to offer prayers to Osun with a calabash of sacrifice prepared by the Priestess, the priest, and other relevant Osun devotees (Orga, 2016). After the prayers, the sacrifice is then carried to the river for offering where everyone present begins to pray earnestly to Osun for individual and collective needs at the river-side.

The votary maid meanwhile retires into the inner part of the temple and stays there till the end of the festival. The king who leads the pilgrimage along the public route to the Ojubo shrine addresses the audience and prays that Osun will make it possible for them to come same time next year and then everyone disperses (Orga, 2016).

The Osun-Osogbo festival officially comes to an end when the votary maid (Arugba) who is the soul of the festival successfully returns to the Osun shrine in the palace. Two bitter cola nuts are placed in her mouth so that she cannot speak out the wondrous things that fill her mind on visiting Osun, therefore, exposing her fate and subsequently that of Osogbo to hazards of stumbling throughout the following year.

ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF OSUN-OSOGBO SACRED GROVE AND FESTIVAL

Cultural heritage has the potential to boost the local and national economy and creates employment opportunities for people especially the youths by attracting tourists and tourism investment. Apart from the cultural and historical significance of the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove, its annual festival is one of the prominent and outstanding traditional religious events that bring pilgrims within and outside Nigeria. This no doubt makes a positive contribution to the economy of Nigeria, Osun State, and the host communities. Given this, Okon (2018) argued that religious tourism is an effective contributor to the socio-economic development of nations, especially in less developed countries as it has resulted in a growth in government revenues and household income directly and indirectly through multiplier effects.

In traditional religion, the numerous festivals held by adherents have added to make religious tourism a beautiful bride that may become a platform for the explosion of tourism in Nigeria. The Osun Osogbo festival is among the numerous religious festivals that have received a huge international following with adherents coming from different parts of the world to pay homage to the Osun river goddess who is believed potent and hold the power to wealth and fertility. According to Orga (2016), Osun-Osogbo annual festival attracts nearly two hundred thousand (200, 000) visitors. The festival and other religious gatherings have made the religious festival a beautiful bride that may become an opportunity for the growth of tourism in Nigeria (Okon, 2018).

Foreign pilgrims as Osun-Osogbo Festival. Source: Wahab (2014)

The tourism industry comprising of hotels, restaurants, travel agents, airlines, and other passenger transport services, as well as the activities of leisure industries, contributed NGN598.6bn representing 1.6% to Nigeria’s GDP in 2011. This progress was projected to increase by 6.3% per annum to NGN1, 223.8bn (1.8% of GDP) by 2022 (WTTC, 2012).

In the area of employment creation, the travel and tourism industry has created numerous direct and indirect jobs, thereby reducing the harsh unemployment heat on the economy. In 2011, the sector created 838,500 jobs directly, representing 1.4% of total employment and it was also predicted that the sector will improve by 1,289,000 jobs representing 3.7% per annum over the next ten years (WTTC, 2012). The Osun-Osogbo sacred grove and festival contributed to the economic progress made in Nigeria’s tourism and travel industry considering the large number of local and international tourists that visit the grove and attend the annual festival. However, the site and festival can still play a significant role in attaining the 2022 projected revenue and employment if adequate attention is paid by relevant authorities in the management of the historic cultural site and festival.

THREATS TO OSUN OSOGBO SACRED GROVE AND FESTIVAL

Nigeria is a nation endowed with a huge cultural heritage which has been a boost to its tourism industry. However, the survival of cultural heritage and its contribution to tourism has come under serious threat in recent times. First is the lack of needed and adequate infrastructure. The unstable and unreliable electricity supply, poor road, rail, and water transport system, lack of hygienic pipe-borne water, absence of quality healthcare system, and the inability of most rural areas in the country to access information and communication network continue to frustrate the growth of many business industries in the country which tourism-related businesses are not exempted. This no doubt has discouraged investors and affected the performance and competitiveness of tourism with other sectors of the economy. Also, the poor maintenance and inability of authorities to rebuilding of the old and collapsed sculptures and structures in the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove defaces the cultural and historic site.

The second threat to cultural heritage tourism such as the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove and festival is the dangerous effect of colonization and western culture. The brain drain associated with the colonization of African societies by different western powers under the guise of civilizing an uncivilized people made many Africans believe and accept western cultures to be superior to their indigenous cultures. The influx of foreign religions such as Christianity and Islam through colonization and sub-Saharan trade and the conversion of many Africans made the converted Africans believe that their religious and cultural practices are fetish and backward. This, therefore, posed a threat to the survival of many African cultural heritages. In recognition of this problem, Adesina (2005) stated that “with the criticism of everything African and introduction of everything European,” cultural heritage resources which is a summary of the past activities and achievement of a group stands the chance of extermination despite its value to the people. Because of the negative notion about African cultural heritages resources, many of them especially traditional festivals have been modified into carnivals to suit modern-day tourists (Ezenagu, 2020).

Thirdly, the rise in urbanization and unguided commercialization of the site and festival is another major challenge. The fast growth of Osogbo into a metropolitan city is causing pressure on land use that was affecting the area around the site. The illegal falling of trees around the grove for timber, illegal hunting of animals, illegal fishing in the sacred river, and illegal cattle grazing affect the biodiversity of the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove (Wahab, 2014).

Also, worshippers at the Osun-Osugbo festival believe the Osun river has the spiritual power to heal sicknesses and make barren women fertile. This, therefore, makes worshippers at the annual event troop to the bank of the sacred river to fetch the holy water. To results in the pollution of the water. In addition, hawking of goods in the grove during the festival leads to indiscriminate dumping of waste and pollution of the sacred site and reduces its cultural and religious significance. As Wall and Mathieson (2006) rightly pointed out that the large influx of tourists to holy sites, their religious significance, which made them famous, is being eroded. In the same vein, Shepherd (2002) opined that immediately a destination or event is sold in the tourism market, it becomes a commodity with a financial value. The consequence of this is that such an event can lose the validity of its sacred rituals to tourists because its economic profit now surpasses its spiritual significance.

Finally, the beauty, survival, and growth of any tourism destination or event are in the ability of the host communities to welcome visitors and offer them the best of hospitality. Tourists will not feel safe and free in an environment where their safety is not guaranteed and welcomed by the host community. One of the star attractions on the 11th day of the Osun-Osogbo festival is the flogging ceremony by youths of Osogbo which is done with flexible twigs of plants to the admiration of the Oba and all spectators. The flogging is done among the youths of the town taking part in the festival. Unfortunately, the harassment of tourists attending the festival with long sticks by Osogbo youths has become a source of worry and discourages some visitors who have been victims of this unfriendly attitude from attending future events.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

The Osun Osogbo sacred grove and festival is indeed a rich cultural heritage and national pride that has contributed immensely to the development of tourism in Nigeria, the growth of the contribution of the tourism sector to the Nigerian economy and has the potentials to make Nigeria a leading tourism destination globally considering its status as UNESCO World Heritage Site. The cultural heritage has attracted tourists within and outside Nigeria because of its religious significance to the worshipers. Despite the cultural essence of the site and its numerous potentials, the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove and festival is faced with challenges threatening its survival, which is mostly human-induced. Given the above-stated problems, there are a need for government institutions at the international, national and sub-national levels to ensure that activities that poses threat to the sacred grove and festival are addressed in line with the sustainable development principle. Therefore, activities such as the illegal falling of trees, hunting, cattle grazing, fishing in the sacred river, and hawking are stopped by providing technologically driven security for the heritage site. Also, perpetrators of these criminal acts must be arrested and prosecuted to serve as a deterrent to others. In addition, there is a need to provide the adequate infrastructure that will improve the tourism experience of visitors at the sacred grove and the annual festivals. At the same time, there is a need to educate locals of the Osogbo town especially the youths on the need to establish friendly relations with tourists and the economic opportunities they stand to benefit from these visits.

REFERENCE

Adesina, O. A. (2005). European penetration and its influence on African culture and civilization. in Ajayi. In S. a. Ibadan: Atlantis Books: ed.) African Culture and Civilization. and philosophy (pp. 122–137). Ibadan: Hope Publications.

Dewar, K. (2005). Cultural tourism. In J. Jafari (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of tourism. (p. 125–126), New York: Routledge.

Edgell, D. L. (2006). Managing sustainable tourism: A legacy for the future. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press.

Ezenagu, N. (2014). Galvanizing culture for Nigeria’s development. Agidigbo: ABUAD Journal of Humanities, 2(2), 87–96.

Ezenagu, N. (2015). Material culture and indigenous technology. In A. J. Ademowo & T. D. Oladipo (Eds.), Engaging the future in the present: Issues in culture

Ezenagu, N. (2017). Leadership styles in the management of Igbo cultural heritage in pre-European era. Ogirisi: A New Journal of African Studies, 13, 22–45.

Ezenagu, N. (2020). Heritage resources as a driver for cultural tourism in Nigeria, Cogent Arts and Humanities, 7(1), 1-14, DOI: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1734331.

Ezenagu, N., and Iwuagwu, C. (2016). The role cultural resources in tourism development in Awka. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 5(2), 1–12.

Ezenagu, N., and Olatunji, T. (2014a). Harnessing Awka traditional festival for tourism promotion. Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Science, 2(5), 43–56.

Günlü, E., Yağcı, K., and Pırnar, I. (2013). Preserving cultural heritage and possible impacts on regional development: Case of Izmir [Internet] Retrieved from http:// www.regionalstudies.org/uploads/networks/documents/tourism-regional-development-and-publicpolicy/gunlu.pdf .

International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) (1999). International cultural tourism charter: Managing tourism at places of heritage significance, ICOMOS.

Leslie, D., and Sigala, M. (2005). Cultural tourism: Management, implications and cases. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann.

National Commission for Museums and Monuments (2010). Osun-Osogbo sacred grove, UNESCO world heritage site 2010-2014, conservation management plan.

Nijkamp, P. and Riganti, P. (2008). Assessing cultural heritage benefits for urban sustainable development. International Journal of Island Affairs, 16(1), 61-3.

Okon, E. O. (2018). Socio-economic assessment of religious tourism in Nigeria. International Journal of Islamic Business and Management, 2(1), 1-23.

Oladeji, S. O., and Olatunji, F. M. (2020). Impact of tourism products development on Osun Osogbo sacred grove and Badagry slave trade relics. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 7(2), 170-185.

Olawale, T. N. and Orga D. Y. (2019). Assessment of challenges and potentials of Osunosogbo sacred grove among staff of national commission for museum and monument, Osogbo, Osun State Nigeria. Journal of Travel, Tourism and Recreation, 1(4), 1-9.

Omisore, E.O; Ikpo, I J and Oseghale, G.E (2009): Maintenance survey of cultural properties in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Journal of Building Appraisal, 4(4), 225-268.

Orga, Y. D. (2016). Tourists’ perception of Osun Osogbo Festival in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Journal of Tourism Theory and Research, 2(1), 41-48.

Oseghale, G. E., Omisore, E. O. and Gbadegesin, J. T. (2014). Exploratory survey on the maintenance of Osun-Osogbo sacred grove, Nigeria. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3 (2), 1-22.

Oviedo, G., & Jeanrenaud, S. (2006). Protecting sacred natural sites of indigenous and traditional peoples. In UNESCO (Ed.), Conserving cultural and biological diversity: The role of sacred natural sites and cultural landscapes (pp. 260–266). France: Author.

Schaefer, R. T. (2002). Sociology: A brief introduction (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Shepherd, R. (2002). Commodification, culture and tourism. Tourist Studies, 2(2), 183–201.

Timothy, D. J., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2009). Cultural heritage and tourism in the developing world: A regional perspecitve. London: Routledge.

Timothy, D. J., and Nyaupane, G. P. (2009). Cultural heritage and tourism in the developing world a regional perspective. Oxon: Routledge.

Tweed, C. and Sutherland, M. (2007), Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landscape and Urban Planning, 83(1), 62-9.

Wahab, M. K. A. (2014). Assessment of the ecotourism potentials of Osun-Osogbo world heritage site Osun State, Nigeria. A thesis in the department of wildlife and ecotourism management. submitted to the faculty of agriculture and forestry in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy University of Ibadan, Ibadan. Nigeria.

Wall, G., and Mathieson, A. (2006). Tourism: Change, impacts and opportunities. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

World Economic Forum. (2015). The travel and tourism competitiveness report 2017, Geneva, Switzerland.

Yale, P. (1991). From tourist attractions to heritage tourism. Huntingdon: Elm Publications.