State-Sponsored Violence: Nigeria and the Politics of Vigilantism

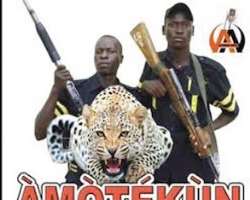

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, is currently experiencing an increase in partially or fully state-supported non-state armed group with Amotekun in the Southwest region, Shege Ka Fasa in the North, Ogbunigwe in the Southeast, while other regions such as the Niger Delta (South-South) are deliberating on forming their own security outfit. Typical of Nigeria’s political violence landscape, the vigilante groups are formed along regional and ethnic lines.

The rise of state-sponsored vigilante group comes against a background of heightened insecurity in the country marked by ten years of Boko Haram insurgency, Fulani militia rampage, frequent abduction and other high crimes across the country. To some extent, the establishment of the regional vigilante groups is justifiable considering the weakness of the Nigerian federated state especially the centralised Nigerian police force (NPF) with its inability to protect the lives and properties of its citizens.

The Nigerian Police Force is underfunded, ill-equipped and incapable of executing its duty of law and order. The capacity of the NPF was undermined by the long years of military rule. Nigeria was governed by successive military leaders from 1983 to 1999, and previously (1966-1979). Although Nigeria has returned to democratic government since 1999 and has had successive democratic leaders since then, the impact of the military, including militarisation and psyche of violence remains.

Nigeria’s peculiar political structure also has an adverse impact on the effectiveness of the NPF. Nigeria is a highly centralised state with a central government based in the capital city of Abuja and 36 states, roughly divided evenly into six geopolitical zones- Southeast, Southwest, Northeast, Northwest, South-South and Middle Belt. Interestingly, the 36 states rely primarily on the oil-dependent federal government for its revenue as much as they do on the Nigeria Police Force for their security. Unsurprisingly, such arrangement creates tension between the states and the federally-controlled police force. To some degree, there is lack of accountability, unresponsiveness to crime, barring the technical inadequacies of the NPF.

Although valid, such explanation is inadequate and limited in explaining the rise of vigilante groups in Nigeria. There is a deep political explanation for the rise of state-sponsored and state-supported non-state armed groups in Nigeria. The Nigerian state with its pluralistic linguistic, ethnic and religious character, presents a dangerous site for contest of power, and therefore proclivity to conflict. It is not surprising that Nigeria is rife with conflicts which include ethno-religious, social and political violence. Nigerian elites have often manipulated the linguistic and ethno-religious differences for their own political gains. Hence, while Amotekun, Ogbunigwe, Shege Ka Fasa represent to some extent a genuine concern and response of the leaders and peoples of these regions to incessant attacks by bandits, militias, criminals and terrorists and the weak response (and, in some cases, indifference) of the federal government, they symbolize a much deeper geopolitical objectives.

Amotekun, Ogbunigwe, Shege Ka Fasa represent political tools to be used as bargaining chips by leaders of these regions to negotiate power in Nigeria’s current federal structure or any future restructuring. These newest vigilante groups form part of Nigeria’s history of regional activism, agitation and struggle for justice, fairness, and equality. They are a resurgence of state-supported armed militant groups such as O’Odua People’s Congress (OPC), Bakassi Boys, Mambilla Militia group and hisbah police. These non-state armed groups were formed shortly after 1999 following Nigeria’s return to democratic government.

The Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) also falls under this category. CJTF is a non-state armed group comprising largely of northeastern Nigerian youth that are assisting the Nigerian military in its counterterrorism operations against Boko Haram and its splinter groups. However, CJTF was originally formed to counter Boko Haram’s terrorism as well as the collective punishment unlawfully meted on the northeastern Nigerian youth by the military who perceived the youth to be collaborators and supporters of the terrorist group. Although CJTF has been assimilated into the military’s counterterrorism operation, one should not forget that it suffered double jeopardy before then. CJTF has been instrumental in most of the successful counterterrorism operations carried out by the Nigerian military, although it has drawn backlash for its heavy-handedness and wanton display of extra-judicial power.

In similar vein, the vigilante groups (such as Bakassi Boys and OPC) set up in early 2000s helped in curbing crime as much as they encouraged extra-legal killings and abuse of power. The recent groups, especially Amotekun have garnered wide support from Yorubas from all walks of life including its religious, political, cultural and intellectual elite. Although it initially drew the ire of the federal government, the central government has conceded to it. The initiatives such as Ogbunigwe, Shege Ka Fasa from other regions have not received similar level of support from its elite. It is not far-fetched to claim that these latest state-supported vigilante groups are at best, the regions’ challenge of Nigeria’s centralized security structure, specifically the ineffective NPF, and at worst, attempt to strengthen their position in any negotiation about power sharing among its elites.

The Nigerian state has applied in the past the principle of consociation in managing the interests of its elites from multiple ethnic groups. This involved the use of constitutions and institutional arrangements as a political technology that accommodates the rights and concerns of the various ethnic compositions with the view of eliminating ethnic domination and determining patterns of authority. Some of the affirmative actions include removing institutionalised barriers against certain ethnic groups, non-institutionalised biases that deny access for certain groups into institutions, institutionalised systemic biases against some groups, quota system (usually non-elective) that guarantees appointment for certain number of an ethnic group, and proportional representation (usually elective) for ethnic groups.

The consociation efforts are guided by the principle of ‘federal character’ that aims at ethnic balance in federal appointments. These efforts have been effective to some extent in limiting ethno-religious conflicts, but the politics of identity, largely primordial identity of ethnicity, has remained defiant to the consociation efforts by the Nigerian political elites, such that ethnicity and regionalism form the tool for mobilising, organising and contesting access to state power.

There is a genuine concern with insecurity and the vigilante groups such as Amotekun respond to this threat and the central government’s (including the NPF) ineffective response. However, underlying such establishment is often a political strategy that each region with its elites employ for greater power and representation in Nigeria’s highly centralized government.