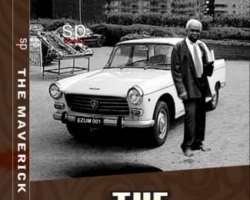

Book review: The Maverick

Title: The Maverick

Author: Chinedu Aroh

Publisher: SCKONUT Productions

Year of publication: 2019

No. Of pages: 240

Courtesies

When Chinedu Aroh informed me that he wrote a book with the title The Maverick and that he wanted me to review it, my first impression going by the title was that it was an autobiography. In my short period of acquaintance with him, apart from his scholarly disposition and our shared experience in journalism, I had found Chinedu quite eccentric. Not until I started reading the book that I found out that the author who has published four other books previously was indeed writing fiction.

The Maverick is definitely not an autobiography, but there is no doubt where the author drew his inspiration from. There is no doubt about the characters in the book and the similarity in the names of people and places. It’s all too familiar that in pronunciation, Ezum comes close to Ezimo, and Nzu (the university town in the book) just needs ‘kka’ to sound like old Nsukka, a town that hosts Nigeria’s premier university.

With a plot set in the rural part of what is today the Northern part of Enugu state, the book is about the contradictions of modernity and one man’s desire -- insistence if you will – to bring his educational accomplishments to bear on how his rural society proceeds on the path of development. In spite of the challenges faced by Iche Obeke, he surmounts the daunting challenges of rural life, surrounded by uneducated folks, to pick some of the prestigious academic prizes in Eastern Nigeria on the way to a scholarship award to study in one of the best universities in Canada. After a first, second and doctorate degrees in Canada plus as associate professorship, he returned to Nigeria as the leading light of his community. A chip-off the old block, Iche is a product of a combination of his upbringing and the environment. He developed an insatiable hunger for knowledge from Mazi Obeke his father. But unlike his father whose quest for education was aborted by primordial beliefs that forced him into an early marriage --- a marriage that was inevitably doomed for failure --- Iche went on to attain those lofty heights in education and scholarship that his father only dreamt of.

His efforts to fulfil his father’s wish that he return to Nigeria and lead the charge of transforming his poor community, definitely produced a different result. Iche may not have expected what he was confronted with. Not only did his own community resist his ideas about his own version of development, he realised that the educational institutions which were to serve as key propellers for character moulding of the future generation had greatly depreciated. More importantly, Iche’s odd character as a non-conformist and a man who would not adjust to the local folks did not help matters either. Being brought up by a father who was taciturn, introverted and separated from the reality of his surroundings may have contributed in shaping his outlook on life, but many will argue that the course he finally chose to read added to his arrogance and his refusal to conform to the society he met on his return.

I will digress a bit. Philosophy as the study of the fundamental nature of reality and existence, many believe, has always brought out attitudes that portray in philosophers as separated from reality. As a way of THINKING about the world, the universe and the society, philosophers are constantly engaged in asking questions about the nature of human thought, the universe and the connections between them. How much he is able to draw logical conclusions from such probing questions is another thing. But don’t take it from them, philosophers are proud people who believe, rightly or wrongly, in the superiority of their reasoning. They are sometimes arrogant and tending to look down on or controvert basic thoughts, beliefs and traditional attitudes and values.

As a journalist, I encountered the late Chuba Okadigb many times. In case many have forgotten, the late Oyi of Oyi held a doctorate in Philosophy, but he usually would not introduce himself as Dr. Chuba Okadigo so you don’t mistake what the doctor is about. He would usually introduce himself as Chuba Okadigbo, doctor of Philosophy, the end of knowledge. In academic attainment, Iche Obeke would stand shoulder to shoulder with Okadigbo in Philosophy.

Iche had good intentions quite all right for his rural kinsmen. This is commendable since it was the wish expressed by his father on his death bed; however, his disposition towards their social problems as well as his response to some of their concerns was as insensitive as they were arrogant. With a first degree in Philosophy, A Master’s degree in Epistemology, and a Ph.D. in African Metaphysics and Realism, all from the University of Toronto, he was clearly conceited and the outcome of his reformist mission in Ezum was easy to foretell. He was operating from a different wavelength and it was to be expected that his esoteric ideas as well as his blunt refusal to adapt to the locals would only bring him in confrontation with entrenched beliefs. And ultimately to the personal failures that dotted his life.

Like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, The Maverick is plotted in a rural African setting with a single with central figure whose rise or fall depended on how he responded to his conviction and issues in the society around him. For Things Fall Apart, it was Okonkwo, and for The Maverick, it was Iche Obeke. Their struggles in their societies are however inverse: while Okonkwo was the symbol of Umoofia’s resistance against the intrinsic cultures of the White man, Iche was the educated local who wished to spearhead the drive to develop Ezum by setting aside its long cherished cultures and traditions. Both ended tragically: while Okonkwo committed suicide out of frustration, Iche’s character and eccentricity got the better of him, so much that he failed in the most important things he set out to accomplish. Everything including his cherished marriage failed, leaving him with a family that became the butt of jokes.

As I conclude, I must say that Chinedu Aroh did a very good job on this book, but I must point a few flaws. One important ingredient in any novel of this nature, especially with fictional reality, is that it should be believable. All the accounts have to add up. In a few areas of the book, there are gaping holes in the narrative. An example is in Chapter 3 where the author accounted for Iche’s return to Nigeria to meet an empty home after 15 years in Canada. The account said when his father died a year before his return, nobody informed him; he only guessed that the man was dead when his letters stopped coming to Canada. For a man who so influenced his life and his education, that was most improbable. The question a reader would ask is: what happened to mobile phones that have become commonplace? And if Chinedu Aroh had set his mind on those colonial days without mobile phones, like for Things Fall Apart, he probably forgot because he wrote on page 22 that Iche returned to Nigeria through the Akanu Ibiam International Airport. Was Akanu Ibiam an international airport in the colonial days?

There are a few others, but they do not seriously hurt the quality of this book which is of a good plot and structurally compact. Indeed, after reading this book, I promised to nickname Chinedu Aroh the Chinua Achebe of Ezimo. Not just because they share the same CA initials, but because of a similarity in their writing. I changed my mind because in spite of the parallels one can draw from both authors, our own CA is actually carving a niche for himself, and I dare say it is a niche that we will all be proud of at the end.

With five books on the shelf already, including Sweet Mother which was mentioned in the Nigerian Prize for Literature Awards 2011, Chinedu Aroh is an author who is still unravelling. I will not hesitate therefore to commend him and recommend this book to the reading public, especially students of literature and critical thoughts.