Comparisons Between Two ‘revolutions’: Omoyele Sowore’s Coalition And The January 15 1966 Coup

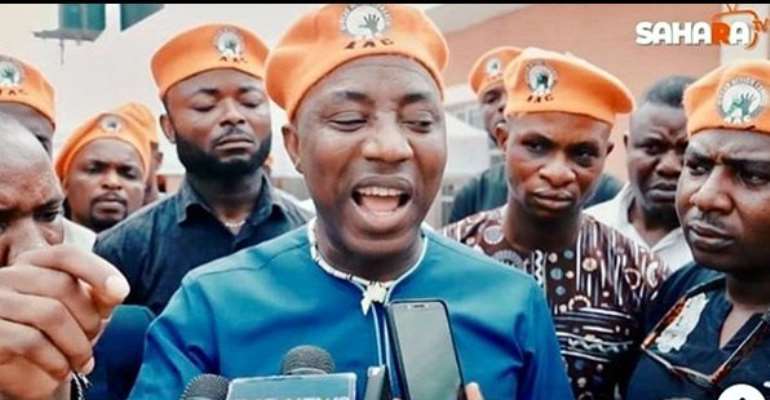

The ongoing national drama over the ‘revolution’ of Omoyele Sowore has engulfed Nigeria and created a theatre where tragedy and farce may end up being staged, if Nigerians are not careful. These are times that try men’s souls in Nigeria and to avoid disaster, it is not out of place to learn one or two things from history.

To the best of my knowledge, Sowore’s civil disobedience/protest/militant agitation campaign is not in the same league as the coup carried out by a group of left-wing, radical army officers on January 15 1966. The plotters called it a ‘revolution.’ Whether it was one is another matter. But there are parallels and comparisons between the two events; the circumstances that led to them and their implications for Nigeria.

First, the contradictions of Nigeria in the years that ran up to the first coup are similar to the situation in contemporary Nigeria. Political instability; ethnic bickering; economic mismanagement and ingrained hostility between the ruling party and opposition; just as it was from 1960 to 1966, so it is from 2015 till date. Corruption was a culture even in the 1960s. Remember Major Nzeogwu’s speech about ‘ten percent’ on the coup day? Although there was nothing like Boko Haram and rampaging Fulani herdsmen in the first six years of our nationhood, those years were years of bloodshed and insecurity. Remember the Tiv uprising in the Northern region and the election-inspired violence in the Western region? The soldiers who struck in 1966 and Sowore’s coalition saw these issues as the demons their ‘revolutions’ must exorcise from the Nigerian space.

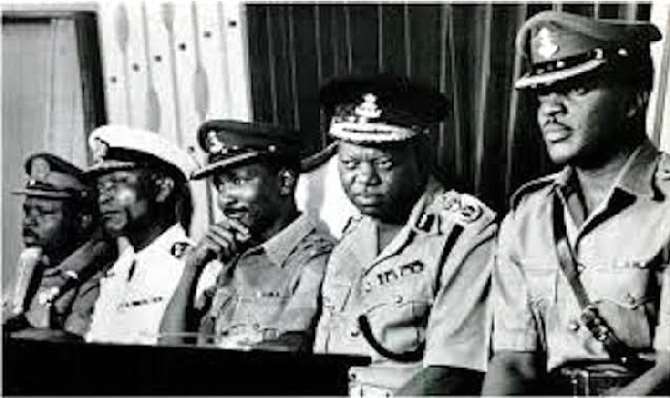

Nigerian Army major Generals In 1966

Second, both movements have been given intense and in my view, grossly inaccurate, ethnic colouration. These ethnic interpretations have diminished both movements and the revolutionary credentials of its architects. Sowore’s Revolution Now coalition has been portrayed by the Coalition of Northern Groups as a Yoruba (South-Western) plot to overthrow Buhari and have called for an end to alliances between the North and South-West where Sowore comes from. But why should Northern groups come to this conclusion? This is my probable answer: given that the concentration of opposition to Buhari’s government is in the South; given that the South-West has been very vocal recently against government actions and policies which appear inimical to people of that area; given that the activist movement Sowore belongs to or leads is mostly dominated by Southern Nigerians (Yoruba; Igbo; Niger Deltans; non-Igbo Easterners with a sprinkling of Northerners, mostly from the Middle Belt), the impression in some quarters is that the South-Western political elite opposed to the Fulani-led federal government have resorted to extralegal measures to get rid of the government that is not ‘their own.’ This ethnic perception is strengthened by the fact that the protests that took place after Sowore’s arrest were predominantly in the South-West. But this ethnic interpretation of Sowore’s ‘revolution’ by Northern hardliners can be seen as giving a dog a bad name to hang it.

The January 1966 coup still bears tribal interpretations till today. None of the political casualties was Igbo. Only one of the military casualties, Colonel Arthur Unegbe, was Igbo. All the inner circle of the plotters were from Southern Nigeria. The executive head of the targeted civilian government was a Northerner. The fact is that the dynamics of the coup and the realities of Nigeria at that time mean nothing to its critics who are the forerunners of contemporary Nigerians reading the same meaning into Sowore’s movement.

Third, and perhaps, most worrisome, are the political pedigrees of Sowore’s ‘revolution’ and the coup. From available records, the January plotters intended to make the then imprisoned Opposition leader, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Prime Minister. Whether Awolowo would have accepted is another matter. This does not mean that Awolowo was privy to the coup in any way. But for me, and probably others who have some insight into Nigeria’s political history from 1960 to 1966, Awolowo’s situation has some similarities with Sowore’s. Both men contested in elections for the highest position in the land and lost to the incumbent. Both men were accused of resorting to undemocratic means to achieve what they could not get through the ballot box. Both men are from the South-West. Interestingly, both men were accused of treasonable felony. Till date, Awolowo��s followers say he never planned to overthrow the government. Sowore’s supporters make the same claim. Students of Nigeria’s sad political evolution know that Awolowo’s trial and imprisonment earned him much sympathy among the country’s young intelligentsia and radicals which included many of the January coup plotters. In contemporary Nigeria, despite criticisms over Sowore’s rhetoric, quite a large number of Nigerians, though not carrying placards or marching in the streets, condemn his treatment by the government and agree with his positions on Nigeria’s problems.

Fourth, the government of the day, just like its 1966 predecessor, seems incapable or unwilling to sincerely engage the troubling situations in Nigeria; situations which are gradually radicalizing some Nigerians to contemplate a blow to the Nigerian state.

Fifth – and this is where Sowore failed to do his history homework – Nigeria is the worst place to contemplate a Castro-style revolution against the bourgeoisie or a Tunisian ‘Arab spring’ against stark injustices. Ifeajuna, Nzeogwu, Ademoyega and other brains of January 1966 learnt this the hard way. In spite of pledges of support, when crunch time came, very few fellow army officers joined the ‘revolutionaries.’ Some openly turned coat. For instance, Major John Obienu’s failure to turn up with his armoured vehicles led to their loss of Lagos. The forces backing the status quo were quick to rally round and crush the coup. And the average Nigerian, for who the plotters supposedly put their lives on line, went on with life undisturbed.

Fast track to 2019. The average Nigerian, despite complaints against the system, regards any radical measure to change things as madness. Believe this: the average Nigerian’s ultimate goal is to take the place of his oppressor, not necessarily get rid of the oppressive system. He desires to make as much or even more money than his oppressor; live the good life; take advantage of the system of rewards when his ‘brother’ is in the corridors of power. In such circumstances, a call to ‘revolution’ seems farfetched.

But Nigeria will be what we Nigerians want it to be. Looking for heroes to lead our quest for a true nation-state or cowing before assaults on our democratic values is not the road to our collective Jerusalem.

Henry Chukwuemeka Onyema is a Lagos-based historian and writer. Email: [email protected]