Martin Luther King Jr.: Injustice Anywhere Not Injustice Everywhere

Injustice and justice differ from one village to another, from one town to another, by ethical injunctions and from one political sovereignty to another. What may seem as unfair or undeserving treatment in one clime might be the beginning of justice and its outcomes in another clime and vis-à-vis.

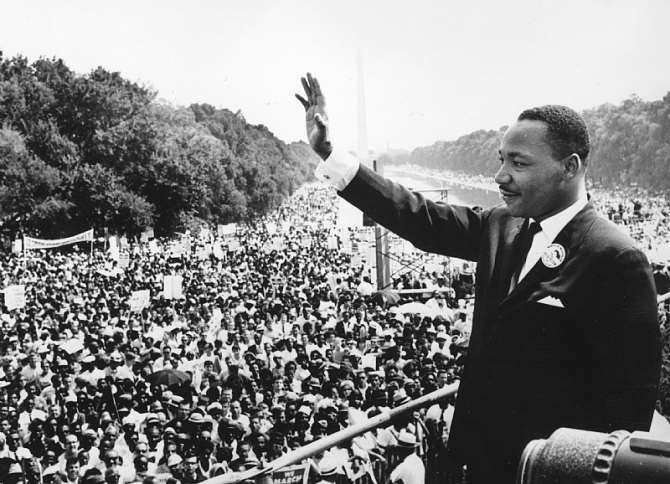

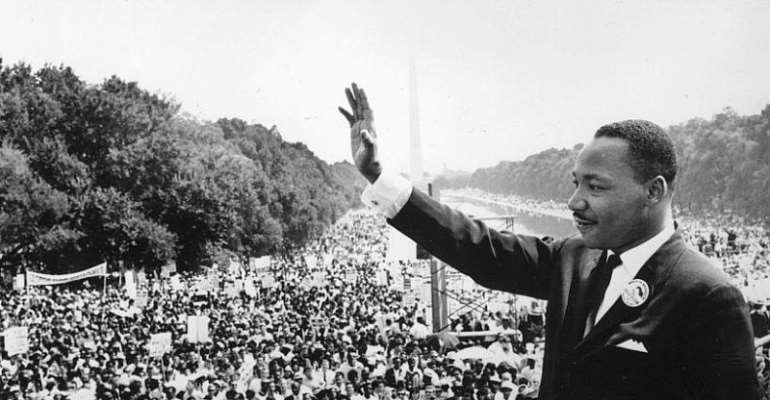

Black American civil rights leader Martin Luther King (1929 – 1968) addresses crowds during the March On Washington at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington DC, where he gave his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

As injustice is the hypothesis of this discourse, we’ll have to draw experience from injustice beyond the interpretation commonly found in Western philosophy and jurisprudence in modern times. Injustice and justice is a susceptible subject to talk about. For instance, if justice is vehemently the practice of fairness in the society by allowing people to get what they want, do we not think people can be given more than they deserve? Against this influence, we must interpret injustice and justice through the periscope of traditions, cultures, and religions predating modern times. We must draw inspiration from laws of different countries. We must interpret injustice and justice through laws that were before and during slavery. We must not undermine such laws and base our argument on the 10 December 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. No. This discourse may not attain the result it was intended to if we base our argument only on human rights. There were other rights before the progenitors of Martins Luther-King Jr. journeyed to the United States of America in the cause of slavery. There were rights that countries observed before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and we must exhume them for posterity.

When the founding fathers of the United States wrote into the Constitution in 1787, there was a provision that absolutely legalised slavery. When they said that “all men were created equal”, they purposely meant the Americans because they did not see the world beyond the confines of their country, their political interest, religious inclination and economy. If they did take to cognizance that “all men were created equal”, they would not venture into slave trade in the first place. They saw what they did as their right – to overlord themselves over others.

By their Constitution in that period of time, slaves were not seen as people but as objects paramount for labour. A quote was credited to Thomas Jefferson as saying. “Blacks and whites could never coexist in America because of ‘the real distinctions’ which ‘nature’ had made between the two races.” This philosophy by Jefferson which, (without doubt, represented the mindset of founding fathers of America), is what political scientists call Political Injustice. We shall unravel the benefits of Political Injustice in our subsequent lines.

We must consider politics played in different climes, their interest, before we define justice and injustice. This brings to bay Political Injustice. Political scientists say it has great benefits. They believe that “he who has the most guns grabs the most property”. They are not concerned about human rights. They are not talking of a failed state but “he who dies with the most toys, wins.” Those who call the shots in such environment regarded as fiefdom extend their practice beyond their “peons and protégés” they have acknowledged under their authority. They also argue that human rights activists see such environment as a failed state, but decorum and a sense of ‘justice’ prevail in it. Accordingly, the points given here disprove Martin Luther King Jr.’s legendary statement which states that, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”