Dialogue is Essential to Unite Cameroon’s Disparate Voices

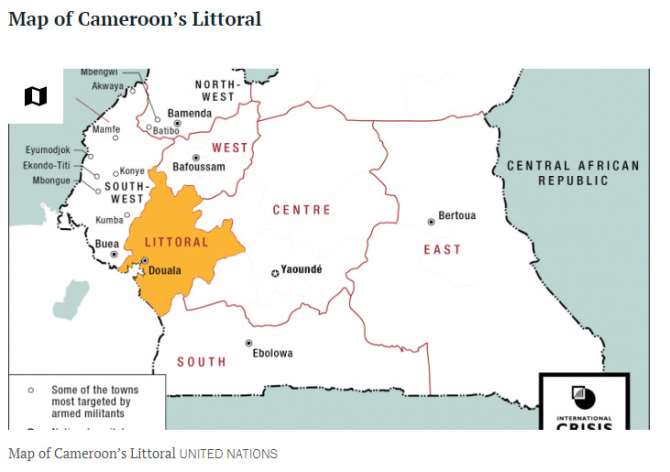

In March 2018, Crisis Group’s Giustra Fellow, Tanda Theophilus, travelled for four weeks to the cities of Buea and Douala, which are at the heart of the Anglophone crisis that pits separatists against the government of Cameroon. He gauged the atmosphere in the Anglophone Southwest and Francophone Littoral regions ahead of the October presidential election.

DOUALA, Cameroon – On the way from Douala to Buea, my vehicle slows at the toll gate on the bridge across the Mungo river, the frontier between the former French Cameroon and former British Southern Cameroons, reunified in 1961. The two regions on either side of the bridge, Littoral and Southwest, are culturally related. Their inhabitants, who are commonly called Sawa, generally call themselves brothers, though some speak French as a first official language and others English. In December, the Ngondo traditional festival brings together people from parts of both regions. But today this fraternity is threatened. The Mungo bridge not only divides the Littoral and Southwest regions geographically, but symbolises a widening gulf between them.

I am in the Mungo basin to learn about the recent fighting and displacement here, and assess warning signs in the run-up to the presidential election, due to take place in October 2018. The conflict, known as the Anglophone crisis, began in October 2016 in the predominantly English-speaking Southwest and Northwest regions and now pits an array of armed separatist groups against the Cameroonian government and security forces. Hundreds of people have died. According to the UN refugee agency, UNHCR, about 21,000 had sought refuge in neighbouring Nigeria by March 2018. According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), over 160,000 had been internally displaced by May 2018 and now live either in the bush of the predominantly Anglophone regions, or in predominantly Francophone towns such as Douala, Yaoundé, Bafoussam and Foumban. Many living in the bush have joined armed groups to fight the government. Dozens of schools have been shut down in the mainly Anglophone regions.

As I pass through the toll gate, vendors rush to our car, hawking bread, garri and plantain chips. I took this road hundreds of times when I was a student at the University of Buea, but until now I had never paid attention to the fact that the peddlers represent a breed of modern Cameroonians: bilingual in English and French, in local Cameroonian forms. In fact, areas like Mungo show that despite the crisis, Cameroon is not neatly divided into two parts where one speaks French and the other English. There are areas like Penda-Mboko (a town administratively located in the Littoral region), that one can hardly characterise as either Anglophone or Francophone. Intermarriages between people of the two regions separated by the Mungo have also fostered bilingualism and blurred the line between the communities.

I arrive in Buea, a town of more than 100,000 inhabitants in the Southwest region. The highest mountain in Central and West Africa, known as Mount Cameroon, Mount Fako or Mongo ma Ndemi (Mountain of Greatness), its native name, overlooks the city. The Mount Cameroon National Park boasts charming florae, some of which grow nowhere else in the world. In Buea’s streets, I hear people speaking both English and French. Many children of Francophone parents study in schools and universities that follow the British system of education, such as the prestigious English-speaking University of Buea (from which I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 2010). This reflects my own life: born and bred in the mainly Francophone town of Bafoussam in the West region, I went to the Government Bilingual High School Bafoussam (Lycée Bilingue de Bafoussam), until I left to pursue my studies at the Anglo-Saxon University of Buea.

But the success of the University of Buea is the exception that proves the rule. Despite the intermingling between English and French speakers, Anglophones, who represent about 20 per cent of Cameroon’s population, have complained for years that the state ignores their cultural specificities and sidelines them in public institutions. Beginning in October 2016, they took to the streets to voice their demands with sit-ins and general strikes. As the government ignored the protests, their anger grew.

In Mile 16 (also called Bolifamba) neighbourhood, where I lived from 2008 to 2010, I meet a group of four young men who were involved in protests that took place first on 22 September 2017 (that day, President Paul Biya was speaking at the UN General Assembly but uttered not a word about the ongoing crisis) and then on 1 October (marking the anniversary of British Southern Cameroons’ independence and unification with former French Cameroon). On those two days, thousands marched from neighbouring towns such as Ekona and Dibanda to the epicentre of the protests in Buea. The men recount how the Cameroonian security forces cracked down severely, arresting numerous people. Some of their friends were shot.

Throughout October, security forces entered and searched homes in Mile 16, including those of these men. On one occasion, soldiers beat three of them. The only one who escaped a beating, whom his friends call MOG (Man of God), was hiding in the bush at the time.

Many Anglophones still live in the bush. Most are young men, but there are also a few women and elders, often undernourished.

Most Mile 16 inhabitants are natives of the Northwest region who have lived there for decades. The neighbourhood has been a fertile ground for both separatist activity and police brutality since the start of the Anglophone crisis. But, that fall, young boys were arrested in other parts of Buea as well, leading many youths to take up arms in support of the separatist cause.

MOG tells me that many Anglophones still live in the bush. Most are young men, but there are also a few women and elders, often undernourished. Not all are involved in the protest. Many are just escaping brutality from security forces. He recently met a lady who had fallen ill in the bush, but did not even have water to bathe.

The four men support a boycott of elections in Buea, in line with the separatists’ vow that voting will not take place in the Northwest and Southwest regions. They are bitter toward the government, and I am astounded by their determination to fight for separation from Cameroon.

Anglophone separatists view Buea as their capital. The city has been politically important throughout its history. It was the colonial capital of the German Kamerun from 1901 to 1916, the capital of Southern Cameroons from 1949 to 1961, and then the capital of West Cameroon until 1972, when Cameroon became a unitary state. Separatists refer to their journey toward self-determination as their “trip to Buea”. They “shall reach Buea”, they say – meaning they will achieve independence. Or they allude to Bongo Square, the plaza in Buea’s Clerk’s Quarter that often serves as a staging area for national festivities and that is considered by separatists to be an assembly ground similar to Tahrir Square in Egypt’s capital, Cairo. It was named Bongo Square after the late Gabonese head of state, Omar Bongo, who visited the city in 1968.

Not far from Bongo Square, I meet Wilfred (for security reasons, all names have been changed), a human rights lawyer defending Anglophones detained in the Buea central prison. He is glad to see me, he says, as it means people are interested in the lawyers’ work.

“About 1,000 people were arrested on 22 September and 1 October, most of whom did not take part in the protests. They were arrested in many places in the Southwest region and detained in schools and in the Mermoz banquet hall, since the prison could not hold all of them. There are cases where whole families were arrested. They were detained for two to three weeks, during which many collapsed, and some women were raped by security forces. However, they are now well treated at the Buea central prison”, Wilfred tells me.

He is optimistic that the detainees will be granted bail, since there is no evidence against them. So far, about 360 people have received bail, but only few have actually been released. Wilfred says arbitrary arrests and the conditions in jail have made many of those detained more likely to sympathise with the separatists. He appears disconcerted about the situation.

Evening falls and I return to my hotel as the town grows silent. Everyone is rushing home to avoid violating the 9pm curfew imposed on and off by the regional authorities in the region’s main cities since the end of 2017. A few hours after I fall asleep, my phone’s ringtone wakes me up. It is about 2am. Someone has messaged me. Half asleep, I read: “Separatists have set ablaze the GSS [government secondary school] Bomaka”.

Ruins of a government secondary school set ablaze by separatists in Buea, March 2018.CRISIS GROUP/Tanda Theophilus

First thing in the morning, I hurry to the school located in Buea’s Bomaka neighbourhood to see the building that has been torched. The school authorities have locked the doors, so people gathered around the windows, trying to peer in at the classrooms. I do the same and see burned ceilings and benches. Arson at schools has become common in the area. According to the UN children’s fund, UNICEF, 58 schools have been damaged in the predominantly Anglophone regions since the beginning of the crisis. Separatists have resorted to this method to prevent classes from resuming. They see stopping classes as an effective way to perpetuate the crisis and to push the government to the dialogue table.

Shortly afterward, I meet Ayah Paul Abine, the president of the opposition People’s Action Party, a former member of parliament and former advocate general at the Supreme Court. Ayah Paul is one of the Anglophones arrested in January 2017 in connection with the Anglophone crisis. During 223 days in detention, he developed a heart condition and almost lost sight in his left eye. Since his release, he has been very ill. He says the crisis is deepening as “separatists have won the hearts of most Anglophones”. In his view, the conditions for a fair vote in the presidential contest are not in place as the security situation in the Anglophone regions is deteriorating and more and more Anglophones reject the election.

“No true Anglophone can be talking about elections now, considering the current crisis in the Northwest and Southwest regions. Things are getting worse. The rainy season is back, and Anglophone displaced persons are suffering in forests. The war [on Anglophone separatists] President Biya is carrying out has radicalised the Anglophones in such a way that it would be difficult for the people to vote”.

He says his party cannot take part in the elections, as, he claims, the ruling party has abducted some of its leaders. He believes that the reunification of Cameroon in 1961 was illegal and that Southern Cameroons has the right to be an independent state, but nonetheless portrays himself as a proponent of federalism – autonomy for federal states within Cameroon, in other words – not independence.

Giustra Fellow, Tanda Theophilus with Ayah Paul Abine, president of People's Action Party, March 2018.CRISIS GROUP/Tanda Theophilus

Since the crisis broke out, thousands of Anglophones have found refuge in the predominantly French-speaking Littoral region – the other side of the Mungo bridge from Buea. Many ended up in its capital Douala, a cosmopolitan city of more than three million. I was there a few days earlier.

Douala, which sits on the banks of the Wouri river, captures the diversity of Cameroon (the country itself is named after the prawns found in Wouri: upon arrival in the fifteenth century, the Portuguese were amazed by their abundance and called it the Wouri Rio dos Camarões, meaning “river of shrimp”). I have been pursuing a PhD since 2015 in the city’s only state university, the University of Douala. It has been clear to me for some time that Douala may be key to a way out of the crisis. It is also one of the few places where I may have access to displaced persons.

Douala is the country’s economic hub. Its inhabitants include not only a large number of Anglophones, but also people from all of Cameroon’s ten regions. Contrary to my expectations, many Douala natives are fluent in Pidgin English and some barely speak French. A lot of people here are bilingual in English and French, sometimes due to marriages between Anglophones and Francophones. Bilingualism is also enhanced by education. Children of Francophone homes are a majority in many Anglophone schools.

The English-speaking teachers are well updated on the crisis and are lukewarm toward the election.

At a government bilingual primary school in town, the complexity of the crisis and its likely long-term consequences again strike me. Mrs Jane, the class 5 (nine- to ten-year-old children) teacher of the Anglophone section, is happy to see me but generally looks worried. She says many pupils from the Northwest and Southwest regions have enrolled in the school since the beginning of the crisis. With the recent arrival of displaced Anglophones, schools in Douala are overcrowded and new ones are opening to accommodate English-speaking pupils.

“The children are traumatised. They are psychologically affected by all they have gone through. They are unable to concentrate during lessons”, she says. “These experiences, coupled with the long stay at home, have affected the children’s performance”. As she speaks, I hear her deep emotional attachment to her students.

“Just yesterday, a student was demoted from class 5 to class 3. His family left Meme division and trekked through the forest to Tombel and Melong before reaching Douala. It is not easy for us teachers. We struggle between their level of performance and their mental state. Many have seen their relatives being killed as they tried to move”, she continues.

Her words come as a surprise to me. “Why would separatists kill civilians?” I ask.

“They kill only blacklegs”, she answers.

A blackleg is a person who continues working when fellow workers are on strike. When the Anglophone crisis started in 2016, protesters used the word to refer to those Anglophones who declined to join or opposed the school boycott. The insult was also thrown at Anglophone teachers and students who continued going to school when Anglophone activists and the teachers’ unions declared a “ghost town” (a general strike intended to make the town look empty). As separatists gained momentum in 2017, they started referring to any Anglophone who does not support the separatist cause or collaborates with the government as a blackleg.

It is not the first time I have heard accounts of separatists killing so-called blacklegs. Two years ago, this level of hatred and violence in Cameroon would have seemed inconceivable. But now, people talk about it without batting an eye. It has become part of their daily lives.

After our conversation, Mrs Jane and I arrange to meet the following day some of the displaced children studying in her school. I am surprised that she is willing to let me interview the children because Anglophones are currently very distrustful of strangers. Mrs Jane tells me that everyone is afraid of me – I could be a government spy. We conduct the interview outside in the schoolyard to let the children speak freely without feeling shy or intimidated by their classmates.

The English-speaking teachers are well updated on the crisis and are lukewarm toward the election. They condemn the January arrest by the Nigerian government of Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, the interim president of Ambazonia (the name of the state that separatists want to create) and, as such, leader of the separatist movement, alongside 46 separatists, in Nigeria and his subsequent disappearance.

The children are originally from Wum, Baba II (both Northwest) and Bangem (Southwest). The pupil I was told the preceding day was demoted from class 5 to class 3 looks particularly traumatised. While some live with their parents, others have been taken in by relatives in Douala.

One of them, Donald, is a nine-year-old boy from Bangem. Around January 2017, his parents and their three children fled growing insecurity there. They made a 40km trek through the bush with other displaced people to Melong (Littoral region). During the journey, a friend of his father was shot dead before their eyes by separatists who called him a “blackleg”. In Melong, the family lived in his aunt’s house for a while. By the time they reached Douala, in mid-2017, Donald and his two siblings had been out of school for more than seven months”.

At an Anglophone secondary school in Douala, I meet Frank, a nineteen-year-old from Angie (Batibo subdivision, Northwest region) who has been in Douala for a week. When the crisis started, he was in secondary school. He recounts the incident that made him seek refuge in the bush.

“One day, as I was talking with my friends, I heard gunshots. Military men shot a civilian and dropped his corpse in the bush. Whenever military men came, they broke our doors and entered. One day, they broke into my room and shattered my belongings. I spent nights in the bush on two occasions, escaping from the military. Every young boy’s life was in danger as the military men brutalised us – claiming that we are the backbone of the crisis”, he tells me.

Over the course of my four days in Douala, I also carry out interviews in the church and with journalists and residents. Many people I meet are angry at the government and do not want to hear about the election. They think that the ruling party will win, whether or not they cast a ballot. This translates into widespread disinterest in current politics. As I move through the city’s brightly lit streets one evening, everyone is merry with music emanating from various directions. This differs from the atmosphere in Buea, where a curfew is in place. I find no sign of campaigning, though senatorial polls are about two weeks away.

Tanda with Cardinal Christian Tumi, March 2018. CRISIS GROUP/Tanda Theophilus

Douala is considered a stronghold of the main opposition party, the Social Democratic Front. The party originates in the Northwest region and draws support in part from the many migrants from that area who have taken up residence in Douala. Its cosmopolitan nature means it has mayors and members of parliament who originate from other regions, a relative rarity in Cameroon. The flag-bearer of the Social Democratic Front for the presidential election, Joshua Osih, is a member of parliament representing the Central Wouri constituency (Douala), though he is originally from the Southwest region.

Douala, like other towns in Cameroon, has seen violence between communities beyond the Anglophone-Francophone tensions. The country’s diversity goes far beyond its two official languages, English and French, with many ethnic groups and a vast array of languages. In recent months, the country has witnessed a rise in hate speech and ethnic tension mainly pitting the Bamiléké and the Northwest region as a whole against the Sawa and Beti tribes (the Beti are found in the Centre, South and East regions; it is the ethnic group of President Paul Biya). Political parties are now viewed along tribal lines.

A famous opposition political party leader based in Douala also believes that the election will see large numbers disenfranchised due to the crisis. She receives me jovially. The situation in the Northwest and Southwest regions has played a major role in her decision not to run for election. She deplores the heavy military crackdown and the humanitarian fallout of the crisis and advocates for an election boycott.

“We can’t take part in elections in which some Cameroonians won’t be able to vote”, she says.

Displaced persons who are willing to vote are not sure they can, first because they no longer reside in the precincts where they are registered, and secondly because some left behind their voter’s cards when escaping the crisis in the Northwest and Southwest. Thus, while Francophones in Douala are free to vote, most displaced Anglophones there will not be able to take part.

The risk of the presidential election provoking violence appears high, as tension rises with the separatists, and moderate Anglophones, having already suffered a humanitarian crisis, are excluded.

As Crisis Group has said since the beginning of the Anglophone crisis, some form of dialogue between the government and Anglophone leaders, with local autonomy on the table is likely the only path to resolving the conflict.

Douala, especially Bonaberi neighbourhood, is increasingly subjected to checks by security forces as its Anglophone population grows. But English speakers have not fled the patrols and, in general, inhabitants have welcomed newcomers with open arms. Many people displaced from the Northwest and Southwest live with relatives who have been in the Littoral region for years. Mr Fru, who lives in Bonaberi, has been hosting his niece from Bamenda (Northwest) since early 2018. He believed the government when it promised that schools would reopen in the Northwest and Southwest regions. He thus went ahead and paid his niece’s school fees. But studies never effectively resumed. He felt disappointed and had to bring her to Douala to prepare for the next academic year.

Although Douala has its flaws, it remains a point of reference for peaceful coexistence in Cameroon. As the Anglophone crisis deepens and tensions between other identities worsen, Douala shows a way out of the conflict. The fact that people with diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds coexist there with few discrepancies shows that a solution is possible. As Crisis Group has said since the beginning of the Anglophone crisis, some form of dialogue between the government and Anglophone leaders, with local autonomy on the table is likely the only path to resolving the conflict.

This commentary is part of Crisis Group’s series Our Journeys , giving behind the scenes access to our analysts’ field research.