After The First Hand Shake

It is no gainsaying that the level of insecurity of lives and property in today’s Nigeria calls the unity and progress of that country into very deep question. Most Nigerians, especially the ones who come from rural and impoverished families in the north-eastern part of the country, no longer have a life.

Over there, the people are slaughtered like chickens every day. The land is soaked with the weeping blood of innocent and hapless Nigerians dragged out of their ancestral homes while they slept at night and murdered just like that, in cold blood. The government authorities appear to be complacent with these daily rituals and blood offerings to unknown gods by home-grown terrorists. Those who survive are sacked from their ancestral homes, and they seek for refuge in neighbouring communities, more than 2 million of them now. Sadly, the life of an average Nigerian from the north-east has no meaning any more.

Daily, the education of young Nigerian girls is nipped in the bud. The girls are kidnapped from school to far away destinations where they are violated. Most of them come from poor struggling families, those whose parents have worked so hard in their farms to see that their children are sent to school. But the insurgents cut them short because they have learnt to strike at targets they consider as soft spots in the system, like schools, churches and markets. The level of impunity that these insurgents now exhibit shocks modern civilisation. What can the people do? What, in fact, can the government do? That is their challenge. That is their song. And we kept wondering. When will all this madness stop? When will Nigeria become quiet and peaceful again?

From far away London, we heard it first in hush-hush whispers. There was a plan in the offing. There was a likelihood that Ohaneze Ndigbo was going to meet with Afanifere to discuss the future of the Nigerian experiment and how they should come into it at this point in time. The one is the apex Igbo Cultural world-wide organisation of the south-east, the other its south-west, Yoruba counterpart.

We wondered. Was it possible that the Igbo and Yoruba would one day sit in one room to table and mutually discuss the future of Nigeria as it is happening to them? We adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

Then it became official. It was all over the place in so many media across the universe, even in advertisements. Elders of Ohaneze and Afanifere, youths from the south-east and south-west, their royal fathers, their governors, the women – in fact, all stakeholders in the Nigerian experiment who hail from south of the country were to meet in Enugu on 11 January 2018. In Enugu, they would rub minds and exchange ideas on the way forward in the current political dispensation. They would deliberate on whether the people of southern Nigeria still had a voice in determining how the future of Nigeria should be shaped. They would discuss the possibility of restructuring Nigeria in its present context and come to a consensus.

The meeting which was dubbed ‘Handshake across the Niger’ was heralded here in London by many southern Nigerians. But some of them received the news with mixed feelings of excitement and caution.

They were excited because they felt that the people of southern Nigeria were at last beginning to shake off their long, deep slumber. Every day, they hear news about very ugly and unpleasant events happening in Nigeria. They hear, especially, of the daily killings of tens and hundreds of Nigerians in the north-east either by Boko Haram or Fulani Herdsmen or some local vigilante group. They hear of the government’s reluctant response to the situations on ground. They hear of the people’s frustration and subsequent self-resignation to the violent whims and caprices and the ever threatening presence of terrorists among them.

Was it surprising that the leaders of the east and west had not thought it necessary to intercede in the conflict that was threatening to crush the country and bring it on its knees? Of course it was. So, if at last they had agreed to come together in unison to look into what the problem could be with Nigeria, it was sufficient reason to be excited.

But then, Nigerians from the south east were also cautious. From their very personal experiences, most people of the south east would be willing to tell anyone who cared to listen that people from the west were as slippery as jelly. They could betray their friend, even to an enemy. The south-easterners believed that with all the ‘power’ the north wields in the present government, occupying all the major security posts in the country, they would be simply taking a huge risk discussing the future of Nigeria’s ethnic components with a people they could not really trust.

The Yoruba, on the other hand, also distrusted the Igbo. They saw them as somewhat dominating and were afraid that any dealings with them would be like subjecting themselves willingly to the domination of the Igbo. In some sense, they would prefer the Hausa-Fulani alliance where they are surer of superior grounds in terms of education and enterprise.

One Yoruba social commentator even posted a recent soul-searching analysis of what he considered as the Yoruba position in the social media, titled “Sad Yoruba Nation?” In the post, the anonymous writer who virtually summarised the situation that had hitherto forestalled the coming together of the Igbo and Yoruba ethnic groups asks:

“Did the Igbo put guns on anybody’s head before buying up Alaba, Ajegunle, Isolo and Oshodi in Lagos? Did they use juju before Ibadan surrendered Iwo Road to them? And what were we (Yoruba) looking at before the Igbo took over Isida and Adeti in Ilesa? Where were the Yoruba when the Igbo thrived and built 90% of the hotels in Abuja? Was there a law that excluded Yoruba from selling building materials? Dei Dei building materials market in Abuja is 90% Igbo-owned.

“So, the more we point one finger at the Igbo, the more we have the other four fingers pointing at our laziness and lack of initiative as a society. The Yoruba should have been better with all our education, but we may be worse than the Fulani who just roam about the bush. Why? It is because we lack the entrepreneurship spirit. We just want salaries from doing 8 am to 5 pm jobs. The Igbo are different hence we are now jealous and envious.

“We love wasteful parties and Aso Ebi. Just a little business without even making any profit, yet we usually call musicians and spray money like confetti.”

Despite these and similar misgivings, those who attended the handshake across the Niger meeting said it went well. They said people came with an open heart. They came in expectation, like bosom friends who were meeting again after losing contact in a long, long while.

The two dominant southern ethnicities were known to have a common ancestry after all. They came from the Kwa Group of the Niger/Congo. But over the years, they had been mutually suspicious of each other. Given the unpredictable developments in Nigeria’s political arena, they had to resolve their differences in the face of the need to restructure the country. That, in essence, was their main focus.

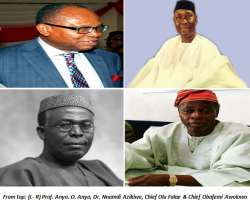

The event which attracted several notable Igbo and Yoruba elite and stakeholders in the Nigeria project x-rayed the past, present and future Igbo and Yoruba relationship and sought for ways to enhance that fraternal relationship.

Among those who spoke was Femi Fani-Kayode, a man whose courage I always admired. Kayode who is married to an Igbo woman spoke eloquently on the ordeal the Igbo had been forced to pass through over the years and insisted that the days of fear were over and that either the present government was willing to restructure the country in its present context or Nigeria would seize to exist as it is known today.

In an interview later, a veteran journalist and one of the vocal Igbo politicians, Senator Chris Anyanwu, was asked what would happen after the initial handshake across the Niger and she confided in the journalist that there would be more handshakes “at different levels”.

Nearly 50 days have flitted past since that initial handshake across the Niger. Nothing else seems to have happened in the camp of our hand shakers since then. The people of the south-east and south-west, especially those in the Diaspora are becoming apprehensive and impatient.

Is the ruling party going to restructure the country or not? What are the recommendations of the governor El Rufai-led commission set up by the All Progressives Congress, the ruling party in Nigeria? When are they going to be made public? And has the government the political will to call for a referendum so that Nigerians will decide for themselves whether or not they want to continue staying together as one indivisible and populous country and if so, by what criteria?

Would the coming different levels of further handshakes represent the people’s will? Or would it be another ploy by the rich and mighty in the south to join the tribal leadership bandwagon that has become the hallmark of Nigeria’s leadership cabal?

Already, the people of south-east and south-west know that tribal leadership pays Nigerian politicians better. Would the different levels of handshake be a manifestation of that sell-out of the people’s hopes and aspirations by the political class? The general elections are scheduled for 16 February 2019 – about 355 days away. And people of southern Nigeria are anxious to know if there have been more handshakes since 11 January and at what level? What is happening next across the Niger, after the first handshake?

* Asinugo is a London-based journalist and the publisher of Imo State Business Link Magazine [Website: imostateblm.com]