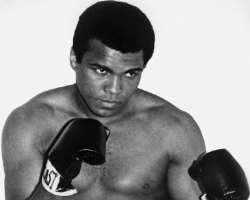

The Greatest Of All Times Retires Home To Ancestral Glory, Fare Thee Well Muhammad Ali!

History is replete with many men and women titled ‘the Great’ and they have all had requiems rising to heavenly heights amidst lavish tributes in annals of the past. While all such ‘greats’ belong to yesteryears of many ages ago or cocooned in epochs of the selective history of conquerors, the most universal and the greatest of all times is none other than the iconic African-American and legendary boxer, athlete, humanitarian, philanthropist, preacher and activist Muhammad Ali who retired home to ancestral glory on June 3rd, 2016 at the age of 74.

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. in January 1942, boxing was what first catapulted the Louisville bred of Kentucky to iconic stardom. At the age of 12 his bicycle was stolen at a local fair. It was his parents’ birthday present to him. Cassius was so incensed he swore to deal drastically with the thief. The Police Officer taking his report immediately spotted talent in the young man. He was a boxing instructor after all. He advised or actually encouraged Cassius to first learn to fight before talking of dealing with thieves. As fate or destiny would have it, the Officer thus became the first trainer of the first true legend and global icon in boxing history.

From winning one amateur title to the other Cassius Clay spiralled into an instant hero at the 1960 summer Olympics in Rome where he won gold in the light heavyweight division. He was 18 only and just six years after the bicycle theft episode. The young hero never looked back. Within weeks of Olympic victory he turned professional and made his debut fighting the 30 years old Tunney Hunsaker in the US. Hunsaker was a Police Officer too but Cassius left him a minced meal, bloodied and battered. Four years later Cassius lifted the world heavy weight title after leaving the reigning Charles ‘Sonny’ Liston so trounced he could hardly leave his corner when the 7th round was called.

The boxing world was stunned by the victory; no pundit had given Cassius a dog’s chance in the run up to the duel. When Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali the very next morning, it was the aftershock following the quake. He announced his conversion to the Nation of Islam and dismissed Cassius Clay as a ‘slave name’. Conversion to Islam was not a very common thing to do in those days of Ali’s America. It took courage and courage he took. He was now Muhammad Ali and insisted that everyone addressed him as such. As if reading the consternation of the mostly white Christian reporters at the press conference, he pointed out that “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want.”

Very quickly Ali got caught up in the separatist rhetoric of the Nation of Islam just as he was caught up in animosities between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, Minister and Messenger in the Nation of Islam. Over the years, and following the assassinations of Malcolm X in 1965 and Elijah Muhammad 10 years later, Ali converted to mainstream Sunni Islam, and subsequently to the Sufi sect. As he matured in age and faith, his spirituality grew beyond religion and sects. He reached out to all faiths and non-faiths. He famously reckoned that “Rivers, ponds, lakes and streams – they all have different names, but they all contain water. Just as religions do – they all contain truths.”

Ali did not just live his time, he shaped it through courage and will power. In 1967 he made a political statement when he objected conscription to fight in a war in which America was then engaged in Vietnam. For him it was hypocritical to conscript him to fight people with whom he had no grudge thousands of miles away when at home his own people suffered segregation and humiliation in the hands of white America. It had not been lost on Ali that he was refused service at a downtown restaurant in his own hometown because he was black. Incredibly, it was soon after he won the Olympic gold medal and was supposed to be an American hero. Alas, not for this ‘whites only’ restaurant. For refusing service in the army, his heavyweight title was withdrawn and he was suspended from boxing in his peak years.

Until 1971 when the suspension was lifted, Ali missed out on the sport he loved so much and which gave him a platform for most other things. Unlike many of us, the indomitable spirit in him never waned, neither was he daunted. He came back from the suspension strong and won the heavyweight title twice more. In the 1975 Thrilla in Manila, Ali knocked out Joe Frazier, albeit technically, in a bout often ranked as one of the best in boxing history or the fight of the century. For the record, Ali had made history by this victory, it was the first time that anyone person had won the heavyweight title three times.

He had already won it for the second time in the previous year when he famously knocked out George Foreman in the 8th round of what was dubbed the Rumble in the Jungle. Until then Foreman was undefeated and the reigning world heavyweight champion. It was all the more memorable being staged in Kinshasa, capital of former Zaire and now DR Congo, in Africa. It was the first heavyweight title bout in the continent and remains the first of its kind. The 60,000 local spectators in the stadium and millions more across the continent chanted Muhammad Ali with great affection and absolute admiration.

Ali truly commanded genuine popularity and fanatical support in Africa for audaciously identifying with the continent and championing the causes of its people at a time of very negative Western attitudes towards Africa and black people. In as early as 1964 he made manifest his affinity with the continent when he announced he wanted “to see Africa and meet my brothers and sisters.”

In that year he toured Ghana, Nigeria and Egypt. The crowds that turned out to welcome him were rapturous for want of a better word. In Ghana he constructively declared that “I am glad to tell our people {Americans} that there are more things to be seen in Africa than lions and elephants. They never told us about your beautiful flowers, magnificent hotels, beautiful houses, beaches, great hospitals, schools, and universities.” He stood out as a leader, a champion and a beacon.

Ali was born an American but remained an African passionate about racial pride and justice. He was indeed the first African-American having been the first to use that term. But the man was much more than an African-American, he had one of the highest likeable IQs and most people from around the world have had an encounter with him even without meeting him in person.

His ability to climb down from the pedestal of personal achievement or summits of public admiration to relate with the mundane and touch the lives of the ordinary is unrivalled. He brought joy and happiness to many in the ring and motivation to many more outside it. As one biographer put it, Ali “housed such an improbable quantity of warmth that it seemed the love he generated could sustain the planet.”

Of all his fights, the one with Parkinson Disease was also one in which Ali was most tenacious and at his bravest. Diagnosed in 1984 with the neurologic condition at the prime age of 42, he immediately became the world’s most famous patient of the disease. People who suffered same found an instant champion in him and he did not disappoint. With the grace of a hero who does not measure life against the worst, Ali never moaned for himself.

Instead he welcomed the challenge and soon put his fame to good use in philanthropy and advocacy. Through his Foundation, the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center, he helped raise over $100million for research and support for patients and their loved ones. In 1996 when he lighted the Olympic cauldron with his hands visibly shaking, his public stand on the disease was both signal and moving. Ali remained his courageous self in his fight with Parkinson until Parkinson finally prevailed over his body and breath albeit not his life and spirit.

When his cortege drove through the streets of Louisville to be interred on June 10th, 2016 the entire city turned out with respect and so did the rest of America and the world, all united in grief and love for one “who became a champion of his people” and “tried to unite all humankind through faith and love”. To cocoon such a multidimensional man in the bubble of a boxing legend only would be the greatest disservice to his memory, trademark and legacy.

As one commentator summed it up neatly, the fight of Ali “was never against anything, it was always for … the dignity of all human beings, regardless of disease, colour, age, disabilities, race and religion.” In his own words, he would want to be simply remembered: "As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him” and one “who stood up for his beliefs.”

We may never have the fisty punch to knock out opponents the Ali way, but we have to be Ali if we truly want to project or eternalise our love for the greatest of all times. To be Ali, we have to have the courage to be a voice for the voiceless, the courage to stand up for our conscience and object the objectionable, the courage to accept adversity and re-channel it into service for humanity, the courage to grow our beliefs and change when change will heal and bridge divides, and the courage to be proud of our heritage and be who we are. If that includes renaming ourselves or going on pilgrimage to reconnect with our roots, we have to have the courage to do so with pride and live our convictions and truth without fear or let. Only then will Muhammad Ali rest in perfect peace!

The writer is the International Spokesperson for Humanitas Afrika