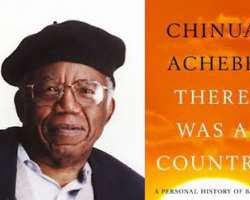

CHINUA ACHEBE - THERE WAS A COUNTRY: A PERSONAL HISTORY OF BIAFRA - MY REMARKS

“Did the federal government of Nigeria engage in the genocide of its Igbo citizens through their punitive policies, the most notorious being starvation as a legitimate weapon of war?

I could hardly contain my excitement when the Eagle on the Iroko announced that he was going to publish his personal history of Biafra. My reaction was: “It’s about time”. However, I still approached the news with trepidation: – Will he boldly lay it all on the line and expose the fault lines in the foundation of Nigeria or will he disappoint and like several Biafran and Nigerian elders bite his tongue and gulp down his own blood in disgust? The Eagle did not disappoint. He called from the top of the Iroko and it was loud, clear and unmistakable.

I decided not to react to the book until I have read every page. In his characteristic style Achebe takes you on a journey beginning at his childhood home with his parents, siblings, uncles, aunts, neighbors. He talks about the values, beliefs, philosophy of life that he learned as a child. Then he talked about his Christian faith and the conflicts and contradictions in the Christian beliefs and the behaviors of the missionaries and the colonial administrators who brought the Christian faith. He discusses his experiences with western (colonial) education, its emphasis on recognition, respect, and reward of excellence, achievement, merit, talent, ingenuity, creativity, hard work, and demonstrable ability.

Achebe painted a clear picture of how his character, identity, and philosophy of life were formed as a result of the coming together of the principles underlying western education on the one hand and Igbo cosmology and world-view on the other. The product of this unification places the recognition of EXCELLENCE at the core of the process of growth, development, and maturity of the Igbo person as well as reward and recognition in Igbo society. This is the essence of the formation of the character, identity, and philosophy of life of the Igbo and to a very large extent other ethnicities in the Eastern Region. Achebe discusses the benefit to Igbo society of this emphasis on excellence. To buttress this point he lists a number of highly successful people from different ethnic groups in Eastern Region (and a handful from Western Region and Southern Cameroon) with whom he grew up. This picture painted by Achebe is the cornerstone of Biafra’s success.

He went on to emphasize how the principle of excellence became the yardstick for recruiting, and deploying leaders who manned positions of authority and responsibility in the emerging Nigerian State in the 1950’s and early 1960. But how will this reliance on excellence work in a multiethnic, multicultural, and multi-religious State like Nigeria where most of the component ethnic, cultural and religious groups have for centuries subscribed to philosophical beliefs and practices that negate and often are overtly antagonistic to the application of the principle of excellence in human development and the organization of society. This was the challenge faced by Nigeria in 1960 as she became an independent nation.

As Achebe begins the story of the march towards independence and the cradle of Nigerian nationalism you immediately sense the beginning of the rift between progressivism buoyed by the principle of excellence and retrogression fueled by feudalism, nepotism, ascription, and corruption. As the British colonialists were about to leave Nigeria they hatched a scheme that would give them full control of the new country from behind the curtain by organizing, supporting, and installing reactionary forces and mustering the fuel of nepotism, and ascription to start a conflagration if the progressive forces dared to insist on excellence in opposition to the decadence they had installed. The scheme worked.

The underbelly of the hopelessly, structurally defective “One Nigeria” became so exposed that the inevitable confrontation came to a head with the January 15, 1966 coup planned and executed by a group of young army officers of Eastern and Western Nigeria origin. The fuse had been lit the previous year with the shameless and unabashed rigging of elections in Western Nigeria followed by total breakdown of law and order and large scale killing of people in Western Nigeria in what was dubbed “operation wetie.” Weeks after the coup, organized massacre of the Igbo and other Easterners all over Northern Nigeria commenced. As Achebe stated:“The weeks following the coup saw Easterners attacked both randomly and in an organized fashion. There seemed to be a lust for revenge, which meant an excuse for Nigerians to take out their resentment on the Igbos who led the nation in virtually every sector – politics, education, commerce, and the arts. The group, the Igbo that gave the colonizing British so many headaches and then literally drove them out of Nigeria was now an open target, scapegoats for the failings and grievances of colonial and post-independence Nigeria.”

Achebe discussed the counter coup, the assassination of the head of state, Major General Johnson Umunnakwe Aguiyi Ironsi, and the pogrom including the last and most horrific slaughter of Easterners in Northern Nigeria which started on the eve of Nigeria’s independence anniversary September 29, 1966 and continued unabated daily for weeks in October 1966. By the time army officers and other ranks, police, customs officers, prison guards, civil servants, clergy, and ordinary folks of Northern Nigeria origin got tired of killing the Igbo and retired to their homes 30,000 -100,000 innocent civilians of Eastern Nigeria origin lay dead, while 1-2 million others battered, bruised, hacked, burned and completely dispossessed managed to find their way to the only safety they had, their homeland in the Eastern Region.

Reactionary forces from Northern and Western Nigeria in collaboration with British ex-colonial forces had fused into a hybrid monster with only one goal in mind – to attack and slaughter thousands of Igbo and other Easterners, dispossess them of their property, kick them out of the positions of political and economic power, drive them out of Northern and Western Nigeria and Lagos back into their homeland and leave them conquered, subjugated, impoverished, and mute. The confrontation between the progressives relying on excellence and the reactionaries relying on nepotism and corruption was in full force and the reactionaries were winning.

Achebe then goes on to discuss the spirited attempts by the governor of Eastern Region, Col. C. Odumegwu Ojukwu and Yakubu Gowon, and other military governors to resolve the impasse and attempt reconciliation. This effort yielded the Aburi Accord which Yakubu Gowon reneged on thereby setting the stage for what Achebe describes as the beginning of the nightmare.

In discussing the two main actors in the In part two of the book Achebe discusses the involvement of the OAU, the UNO and the superpowers like the United States. Achebe then goes to great length to discuss the roles played by foreign and Nigerian intellectuals and artists especially writers like Wole Soyinka, Chris Okigbo, Cyprain Ekwensi and others. In discussing Nigerian intellectuals in the context of the Nigeria – Biafra war Achebe made one profoundly revealing statement: “The war came as a surprise to the vast majority of artists and intellectuals on both sides of the conflict. We had not realized just how fragile, even weak, Nigeria was as a nation.” [p. 108]. This revelation is astounding because even today some of our intellectuals, and politicians, especially those from Eastern Region have no insight into the incongruity of the One Nigeria boondoggle.

Achebe then makes an even more critical statement:“No small number of international political science experts found the Nigeria – Biafra War baffling, because it deviated frustratingly from their much vaunted models. But traditional Igbo philosophers, eyes ringed with white chalk, and tongues dipped in the proverbial brew of prophecy, lay the scale and complexity of our situation at the feet of ethnic hatred and ekwolo – manifold rivalries between the belligerents. Internal rivalries, one discovers, between personalities, across ethnic groups, and within states, often fuel the persistence of conflicts. Conflicts are not just more likely to last longer as a result of these rivalries but are also more likely to recur, with alternating periods of aggression and peace of shorter and shorter duration.” [p.123].

Here lies the key to understanding the true nature of Nigeria’s problems and why no amount of cosmetic band aid can patch up the deep wound on Nigeria. Deep rooted ethnic hatred often directed against the Igbo, is key to understanding the persecution of the Igbo in Nigeria. This is not fantasy; it is not fear mongering; it is not overreaction.

[Read the reactions to this book from intellectuals, leaders of thought, politicians, etc from other ethnic groups in Nigeria; watch the video of Alhaji Ahmadu Bello, first premier of Northern Nigeria on Northernization policy; read the original Charter of Egbe Omo Oduduwa; read the comments of members of the Northern Nigeria House of Assembly during the budget session of the House in 1964; read “On a darkling plain” by Ken Saro Wiwa; read the comments of some Nigerian Army commanders during the war on “how to solve the Igbo problem.”]

Achebe then discusses the invasion of the Mid West by Biafran forces, the betrayal by Col. Victor Banjo followed by the slaughter by Nigerian troops of 700 innocent unarmed men, the cream of Asaba community; 300 men, women and children praying in the Apostolic Church in Onitsha; 2,000 innocent Igbo men, women, and children at Calabar and an unknown number at Uyo, Ikot Ekpene, Owerri and Amaeke Item, Port Harcourt, Abakaliki, and other towns. Achebe recalls the activities of Benjamin Adekunle who described humanitarian aid to starving Biafran children as “humanitarian rubbish” and boasted “we will shoot at everything that moves and when we get into Igbo heartland we will shoot at everything even those that do not move.”

Achebe then goes on to discuss how Biafran intellectuals formed the core that articulated the principles of the Biafran Revolution which was the guiding philosophy around which Biafra’s national social, cultural and technological identity was woven. He discussed the different ethnic groups that made up the Biafran Nation; the philosophy and politics behind the Biafran flag and national anthem. Then he goes into a little detail discussing the Biafran army; the indomitable will of Biafrans to innovate, and create their own weapons. He discussed the ingenuity which resulted in RAP engineers producing such deadly weapons as Ogbunigwe.

Achebe then moves on to discuss his activities travelling overseas as roving ambassador of Biafra. He discussed the impact of the budding Citadel Press which would have brought together the mass of highly talented writers in Biafra. This prods the reader to imagine what this press and its products could have done for the minds of Biafran children, their self-esteem, creativity, ingenuity, and their identity, and even more importantly for their belief in their own prowess had Biafra been left alone by Nigeria. Achebe concludes part two of the book with a discussion of the refugee situation and the beginning of starvation of Biafrans by Nigeria.

Achebe starts part three of the book with a discussion of the total economic blockade of Biafra by Nigeria and her allies and the massive starvation unleashed by Nigeria on Biafran babies, children, pregnant women, nursing mothers, old women and old men in the name of keeping Nigeria one. He discusses the mind-numbing, figures of innocent, non-combatant children starved to death everyday (one thousand) and every month (fifty thousand) by Nigerian leaders. He pulls in the international dimension of this crime especially the complicity of the British Government of Harold Wilson, and the deafening silence of the United Nations.

At this point Achebe lunges at the elephant in the room – “Did the federal government of Nigeria engage in the genocide of its Igbo citizens through their punitive policies, the most notorious being starvation as a legitimate weapon of war?” He then queries why the Nigerian government has purposely tried to suppress any discussion of what happened during the war, or taught young people a history of that sordid past forty years after the war ended.

He kick starts the debate by quoting from a very well researched book on the genocide committed by Nigeria on Biafrans – “The Brutality of Nations” by Dan Jacobs, 1987. [By the way if you want to get a clear, unbiased picture of the crime of genocide committed by Nigeria on the Igbo, please read this book.] Achebe then goes on to support his argument of genocide on the Igbo with quotations from Pope Paul VI; distinguished American historian , Arthur Schlesinger; former American President, Richard Nixon; distinguished Canadian diplomats, Andrew Brevin and David MacDonald; New York Times journalist, Lloyd Garrison among others.

Then he clearly lays out the case against the leadership of the Nigerian Government - Chief Obafemi Awolowo, General Yakubu Gowon, Allison Ayida, etc. detailing not only the starving of Biafrans during the war but Nigerian government policies after the war. He discusses policies designed to permanently impoverish and destroy the Igbo economically and politically – policies such as the federal government confiscation of all Igbo money deposited in Banks all over Nigeria before the war, arbitrary award of twenty Nigerian pounds to each Igbo family after the war irrespective of how much they had in their bank account before the war and whether or not they operated the account during the war; the Enterprise Promotions Decree 1974; the willful, calculated official discrimination of and removal of all Igbo from senior positions in the armed forces and civil service, the charade of the three R’s – Reconstruction, Rehabilitation , and Reconciliation. Part three of the book is almost the shortest of the four parts of the book with only 30 pages. Surprise! It has generated the crudest, loudest, and most acerbic outburst from Nigerians.

In part four of the book, Achebe does an appraisal of the current situation in Nigeria right now. He concludes that Nigeria has descended into the abyss of hell. He states that since independence in 1960 Nigeria has grown steadily worse by blatantly denying people their democratic rights, and human rights; ushering in all manner of banality and ineptitude and destroying the principles and systems that reward excellence and respect talent, creativity and achievement which formed the cornerstone of progress in Igbo land.

He goes on to describe the philosophy, and principles underlying the organization of Igbo society – republicanism, respect of talent and excellence, achievement orientation, antimonarchy, and anti dictatorship. He concluded by surmising that what Nigeria needs is the selection of a good leader. He seems to come to this conclusion by looking at the example of former South African president, Nelson Mandela who resolutely stayed in prison for 27 years just to get his Black South African brothers and sisters to dismantle apartheid rule in South Africa and secure freedom for his people.

There Was a Country may not be the most popular of Achebe’s books now, especially with Things Fall Apart a classic, but it might eventually become the most important work of his life. He has turned the searchlight on the most dastardly genocide in Africa in the 20th century committed by Nigeria on the Igbo and other people of Biafra. The Igbo holocaust provided the 20th century model and foundation for Rwanda, and Darfur. Yet it surpasses them in numbers murdered, the brutality, and the comprehensiveness of the method employed. In its callousness, and inhumanity it can only be compared to the Jewish Holocaust – the starvation and gassing of six million innocent Jewish men, women and children in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald, Mauthausen by Germany’s Hitler and the Third Reich. The story of Igbo genocide almost effectively buried for forty years is finally being told by the victims. Go on YouTube and search for “starved Biafran children” and you’ll see disturbing pictures that were taken during the genocide.

International Institutions, and to some extent, Germans themselves have held their leaders accountable for the Jewish Holocaust. How about Nigerians; have they held those Nigerians who planned and executed the Igbo genocide accountable? What has been the reaction of Nigerians including the children of those who committed genocide to Achebe’s book detailing the atrocities? In a single word, “SHOCKING”. Achebe reproduced Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s articulation of and justification for starving millions of noncombatant babies to death. Then he went further to advance his hypothesis of why he thought the Gowon Cabinet implemented the starvation policy as well as other economic and administrative policies – “……to stunt, or even obliterate the economy of a people….” P.234. On Chief Obafemi Awolowo he postulated “It is my impression that Chief Obafemi Awolowo was driven by an overriding ambition for power, for himself in particular and for the advancement of his Yoruba people in general. And let it be said that there is, on the surface, at least, nothing wrong with those aspirations” p. 233. To Nigerians from the North and the West, Achebe has spoken heresy; he criticized General Yakubu Gowon and his cabinet for brutally murdering 3 million innocent Igbo children; He also criticized Awolowo and advanced his impression of Awolowo’s motivation for his actions. True, we can’t tell with certainty someone’s motivation for their behavior. But Achebe is at least entitled to his impression. All you can do is challenge it, disagree with it, and may be advance your own impression.

However, for months Nigerians from the West and the North have declared war on Chinua Achebe. They want to dethrone him at least in the intellectual world [which is like trying to cut down a fully grown Iroko tree with a bread knife]. These Nigerians have gone to war not only against Chinua Achebe but against the Igbo, General Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, and Biafra. It is shocking but not surprising. Listen to some of those comments: “The Ibos caused the war, and till today, they refused to accept responsibility for it ….” “Ibo people died as a result of the civil war, Obafemi Awolowo did not kill them; they were killed by the war which was the result of “madness” and “recklessness”. How convenient it would be to simply say that three million Igbo children just died – nobody killed them; just like saying that six million Jews just died in the concentration camps in Europe – nobody killed them – nobody is responsible. “The Ibos are vociferously attacking the Yoruba people, forgetting that the safest place for the Ibos presently in Nigeria is Yorubaland.” “…… While the Hausa man was killing them in the North and the Rivers people were taking their properties in the South-South, the Yoruba was helping them to collect rent on their properties in the West …” “Professor Achebe has a personal hatred for the sage because of the nomination of Professor Soyinka a Yoruba man for the Nobel award and his eventual emergence as the first African Nobel Laureate. He is not pleased that he didn’t receive the Nobel Prize.”

“The Civil War was started by the Igbo.” “If the statement credited to Achebe is true, then he has just declared himself as an enemy of the Yoruba race.” “Achebe is a pathological liar” “Achebe’s statement on Chief Obafemi Awolowo is an outburst” “Achebe has descended into the arena of Biafran propagandists who are always ready to sacrifice the truth to achieve emotional blackmail.” “I find the foremost novelist lambasting of our iconic politician and impeccable leader, Chief Awolowo utterly strange. But why should we really be surprised? Even in death, Awo, our Awo, is still the issue. This being said, we must dismiss the illustrious novelist who must sell his autobiography. He needs to attack Awo for the book to make appreciable sale, an inroad in western Nigeria of solidly educated and civilized denizens. …. Now we must ask, did he expect Awo to devise a strategy for Biafra to defeat Nigeria?” “Simply put, by writing this book and making some of these baseless and nonsensical assertions, Achebe was simply indulging in the greatest mendacity of Nigerian modern history and his crude distortion of the facts has no basis in reality or rationality.” “Whatever starvation was experienced in Biafra was self-induced.” “In my opinion Achebe’s book is tribal and inconsistent with the truth.

The Hausa did not deny killing the Igbo. And as General Haruna said at the Oputa Panel in 2001, he had no apology for that. Bringing the 3MCDO into it and Awolowo in a derogatory way is evil and ungodly. Contrary to the starvation stories being bandied, the 3MCDO were feeding natives and Biafran soldiers to the extent that the federal troops under his command were feeding once in a day.” “It is so easy to kill the Igbo because they own the sales of attractive items like cars, electronic items, building materials, and others. The Yoruba man in the North or East is a low-lifer. The man drives a taxi, while the wife sells amala. As soon as there is unrest, the wife puts the cooking pot in the taxi and home they go.” “As the commanding officer and leader of the troops that massacred 500 (700) men in Asaba, I have no apology for those massacred in Asaba [Onitsha, 300], Owerri, and Ameke-Item. If General Gowon apologized he did it in his own capacity. As for me I have no apology.” In his reaction General Yakubu Gowon, Nigerian Head of State 1966-1975, described Achebe’s book as: “A propaganda …… written to whip up unnecessary sentiments.” He stated: “Many books have been written about the civil war and unfortunately none had been as controversial as that of Achebe, which accused me and Chief Awolowo of genocide against the Igbo.

Nothing can be further from the truth, because every decision we took was for the interest of a united Nigeria … I’m not aware of any Igboman that has an account with the then Barclays Bank that was seized, because at the end of the war many of them got their money back. And it was because of our resolve to ensure that there was no victor no vanquished. We put in place a lot of measures to ensure that everybody was reintegrated into a united Nigeria.” He then summed up his case against starvation thus: “Most of those who accused us of genocide were looking well fed at the end of the war.”

Nigerians have never held their leaders accountable for their deeds before, during and after the war. It was so during the war; it was so immediately after the war; it has remained so since the end of the war. This is why Nigeria won the war but lost the peace. The reaction to Achebe’s book provides the clue – naked tribalism fuelled by ancient, unrelenting hatred of the Igbo by other Nigerians. What is happening to the Igbo in Nigeria is not “Ekwolo” – (Stiff competition), it is “Ikpo-asi” – (Hatred). Your competitor wants you around so he can defeat you and claim the glory of victory. The person who hates you does not want you around; he wants you dead and gone. He does not want to compete with you. He just wants you out of his way. This is why Nigerians have attacked and slaughtered the Igbo uncountable number of times from 1945, 1953, to 1966 and relentlessly from 1980 till today. It will not stop. It will continue no matter who is the leader of Nigeria.

Achebe writes about 1-3 million children starved to slow, painful death by the policy of starvation articulated and implemented by Nigerian leaders including Chief Awolowo and what was the response from Nigerians? Did you hear remorse? Did you hear regret? Did you hear outrage? Did you hear shock? Did you hear “Oh no that was wrong”. You heard none of that. What you heard was outrage at Achebe for “insulting” their “sage”, their “infallible sage”. What was even more shocking was their justification of the starvation policy and insistence that they did what they had to do because it was war (on babies and children). This is what Nigerians in 2012/13 are saying about the fact that their leaders murdered 1-3 million babies, children, pregnant women, nursing mothers, old women and old men in 1967-1970.

Compare the reaction of these Nigerians to the reaction of Americans to the killing of 20 children by a crazy gun man at Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012. The president of the United cried at a public press conference while the entire United States citizenry convulsed at the thought of twenty of their children murdered in cold blood. Compare the reaction of these Nigerians on Igbo genocide to the reaction all over the world to the shooting of Malala by the Taliban, the rape and death of one Indian girl by sex-crazed Indian men. What kind of conscience do Nigerians have? What moral compass guides their thinking, reasoning, logic, and emotion especially when dealing with “Igbo”? I can only think of one thing – “HATRED”, deep-rooted “HATRED”.

So what does the future hold for Nigeria? It will be soothing to the souls of Nigerians and their friends to say that there is hope for the country but reality dictates otherwise. The fundamental flaw in the foundation of statehood has not been addressed and actually appears intractable. Should Nigerian society be organized on the basis of excellence or mediocrity? The reason not to be hopeful is that mediocrity has become the ladder through which most ethnic, cultural and religious groups in Nigeria have risen to positions of power, prominence, wealth, and success. They will do whatever it takes to maintain the status quo and will do everything in their power to stifle any attempt to revert to excellence. But it is also clear that mediocrity breeds inefficiency, poverty, instability, failure and ultimately entropy.

This is why Igbo must separate themselves from Nigeria or be destroyed. In one of the Nigerian internet forums a Nigerian asked a relatively simple but deeply meaningful question: “What kind of people get killed, rejected over and over in a place and they keep going back to that same place- what kind of people” he wondered. This is a question every Igbo must ask himself or herself.

Any Igbo who lives and does business in any of the twelve Sharia states of the North knows that he is playing Russian roulette with his or her life. Life has become hellish for the Igbo living in Northern Nigeria. How about the West, is it a bed of roses? You make the call.

Yakubu Gowon is listed as number 10 on the list of the worst mass murderers in the history of the world for murdering more than one million Biafrans. It must gladden Yakubu Gowon’s heart to be in the company of the most evil men in the history of the world. That’s where he will be forever and ever. As I look at Webster’s Atlas published by Barnes and Noble in 1997, I see Biafra clearly demarcated there and it confirms to me what the Irish Roman Catholic Father Joe who worked in Biafra saving the lives of starving children till the end of the war said in 1970 as Biafra was overrun, “Remember now: however this thing is settled militarily, somehow, somewhere, something called Biafra will continue to exist.”[Breadless in Biafra]. There was a country and there will be a country called Biafra.

Written By Dr. Emma. Enekwechi.