NOLLYWOOD THROUGH PIETER HUGO’S LENS

Dirk Bogarde was quoted to have said that the camera can photograph thought. Therefore if the collection of pictures, the South African photographer named Pieter Hugo has been exhibiting over the world as a reflection of Nollywood is his thought about the Nigerian film industry, then this thought is not only unapprised but unschooled. Those images alone made my skin crawl.

The level of interest and/or contempt Nollywood has generated is such that emergency critics have been made of people who have never seen a Nollywood movie. Some have turned their apathy towards Nollywood into status symbol. In the main, Mr. Hugo's collection of photographs about Nollywood, evidence a conclusion based on a stereotype. It is an intelligent effort to creatively manage ignorance.

The photographer assembled a team of 'actors' and assistants in Enugu and Delta States to recreate scenes fresh from his nightmares and name them Nollywood verisimilitude. From February 25 – April 10 2010, these weird pictures were on exhibition at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, USA. The same exhibitions have been held in Rome and California to critical acclaim from an elite tribe of the uninformed

Grotesque images

In one of his images we see a cutlass through the heart of a woman, the bodice ripped wide and the loose breasts roll. A female gang of three wielding rifles, a lady wielding a rod, eyes rolled in semi-consciousness and hands protruding from her mouth. There is another of a vampire-like creature wielding a rifle with children gaping at the background. And another of a burnt corpse emerging from the wreck of a vehicle… Pray how does this lunacy reflect Nollywood?

The props used in the re-enactment of Pieter's nightmares range from machetes, screw bars, hammers and firearms. They often look extraneous to the setting. The images lack balance; it creates a subjectivity of only the dark kind.

The characters, in the main, didn't need the efforts of a Make-up artiste to look hideous; their parents made that easy. And that perhaps seemed to be the only redeeming thing in the horrid collection. Mr. Hugo's ability to assemble a cast of characters that seemed to have crawled out of slime is indeed remarkable with their faces like a stretch of unpaved road. Perhaps, he should google Genevieve Nnaji or Mercy Johnson, or Ramsey Nouah… these are sights for sore eyes and they are all Nollywood acts. There are many more too numerous to mention in a single breath.

The settings of the collection are dreary, bland or outright creepy. For emotion, there is dread and an uncanny melancholy. They seem to choke you as they gasp for air to breath. The subjects fly out at your face, you lock eyes with them and you will be the first to avert a gaze. In Nollywood films, we see palatial mansions, choice cars and pleasing sights. Nollywood destroyed the myth that Africans still lived on trees.

When images this grotesque are collected as part of a continuum, they tell a story powerful enough to influence thoughts and colour judgment. It is even worrisome when they seemed to have been formed upon the canvass of a lie. They feed on the imagery that Nollywood is only digitally enhanced voodoo. Even if this is the intent, they miss an important link. There is a curious disconnect between voodoo as seen in Nollywood and their relation to reality. Worse still, they ignore completely the place and purpose of rituals in African thought.

Through the aid of 3D and superior technical expertise, Hollywood monsters appear cooler than those of Nollywood. Yet, to judge Nollywood's rendition upon the standards set by Hollywood is to judge a Miss World pageant with a condition that all the contestants must be white. The monsters created in Nollywood do not just help the story along, their intent is both creative and didactic and often with spiritual connotation. Pieter Hugo's images share no such similitude. They are the stuff of nightmares.

Writing about the images, Stacy Hardy wrote “Pieter's monsters confront us on their own terms; head on, they stare us down. Instead of lurking in the shadows or hiding under the bed of our eternal subconscious nightmare, the figures are starkly light. Their bodies undo sight. Monsters from a nation's Id suddenly demanding equal time as thinking and dreaming and sexual citizens. They face us without even the faintest glimmer of a possible absence, in the state of radical disillusion; Baudrillard's “obscene transparency” of “pure presence.”

Nollywood is not all voodoo

Pieter Hugo's collection is hardly what Nollywood represent. Nollywood is an extension of African story-telling culture. The images created in these stories find relevance in their power to reprimand and teach object lessons. To achieve this objective, fictional characters are given human personae though inanimate or non-human. The subjects in Pieter's images do not satisfy this need.

And this really is the power of the phenomenon called Nollywood. It is the spirit of a people to re-create their world first for themselves and invite others to share in their reality. It is the power to laugh at our own idiocy without the embarrassing stench of self-deprecation. It is the ability to define our world without the burden of borrowed and often skewed lenses. Ansel Adams said that “A photograph is usually looked at - seldom looked into”.

I have looked into Pieter Hugo's images of Nollywood and I can smell the stench from a mile away.

Isaac Anyaogu, writes film scripts.

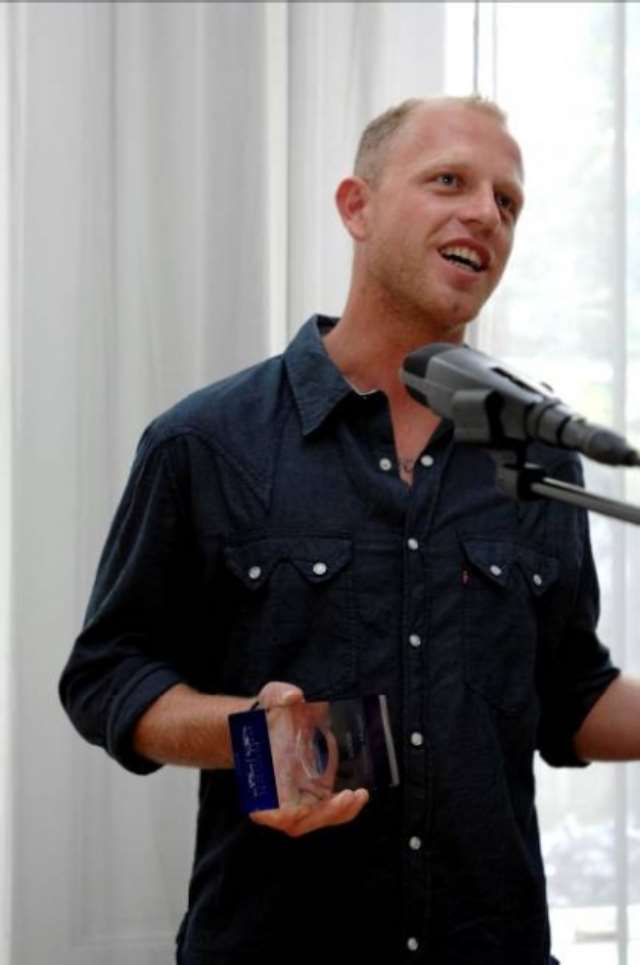

Pieter Hugo