Create Ébrié Lagoon Authority, UNEP Urges Government

ABIDJAN 25 September – Côte d’Ivoire’s highly polluted Ébrié Lagoon needs a dedicated agency to spearhead its restoration and ensure its continued health, the United Nations Environment Programme recommends in the first post-conflict environmental assessment report for the West African country.

The Ébrié Lagoon Authority, as it would be, would undertake long-term planning of the lagoon and its adjacent areas. The authority would ensure effective coordination between relevant municipalities and government departments, UNEP says in the report, to improve the environmental quality and productivity of water bodies. This is what bodies such as the Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia (the Venice Water Authority) have done to manage the city’s lagoon.

Conflict is thought to have been the reason for the current level of rot of the Ébrié Lagoon. However, it was already badly polluted before the 2011 civil war. Today, it has become a solid, liquid and industrial waste dump from Abidjan. Contamination by agricultural chemicals, especially pesticides, transported to the lagoon from the runoff has compiled the problem.

“In many places, the concentration of pollutants exceed standards to the point that biodiversity and aquatic ecosystems are under direct threat,” UNEP says in the report delivered 16 September to the Ivorian Ministry of Environment, Urban Sanitation and Sustainable Development.

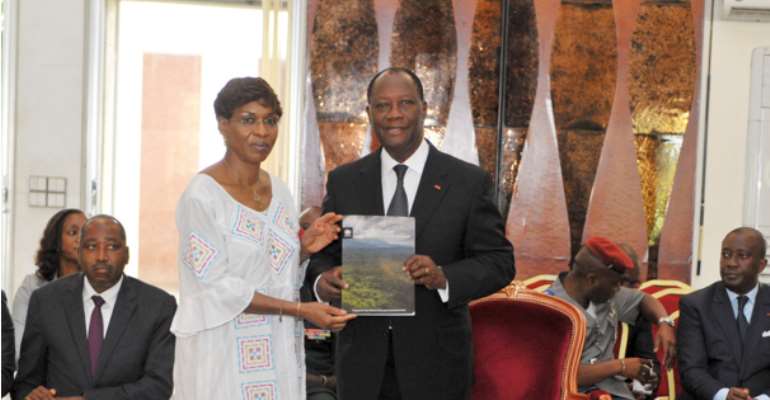

United Nations Special Representative Aichatou Mindaoudou handed over the report 25 September to President Alassane Ouattara.

Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara, right, receives Friday the UNEP Post-conflict Environmental Assessment Report from United Nations Special Representative Aichatou Mindaoudou.

Pollution Sources

Sources of pollution are diverse. Abidjan’s explosive population growth, doubling to 5 million according to the report, as a result of the war is one. People fleeing the war have refused to return to their regions. Many have settled in makeshift shelters on any available space eastward along the lagoon. In equal measure, occupants of these areas have been routinely dumping waste into gullies, hollows, streams and the lagoon. Their presence and actions have depleted groundwater sources and continue to feed pollution of the lagoon.

Other damage has come from sewage and waste disposal, landfilling, and the scuttling of unwanted ship and industrial waste. CIAPOL, the state-run Ivorian Anti-pollution Centre, estimates that 20,000 tons of waste oil is generated every year by the transport sector. The UNEP report also says some of this oil is reused as fuel, “but an unknown amount is discharged into the sewer system or directly into the lagoon”.

Formally, Abidjan’s rainwater drained into open channels, then into large open-air collectors and finally into the lagoon. However, the influx of people into Abidjan that began in 2002 has overwhelmed the wastewater collection network.

In areas of illegal and unplanned settlement, rainwater drains are crammed with solid waste. This is so for secondary drains and main collectors, according to UNEP which adds, “The rainwater collector ending in Cocody Bay can scarcely be distinguished from an open sewer.”

In Abidjan’s largest commune, Yopougon, the collector from the industrial zone and household wastewater caters to some 1 million people. The UNEP report adds that wastewater from this collector and from the adjacent areas is discharged into the open, and has carved a deep valley in the area. During the rains, water gushing into the valley erodes its edges, collapsing homes and sweeping them away in floodwaters.

“Sometimes people fall into the sewer and drown, their corpses found in the lagoon,” UNEP adds in the report.

Medical and Industrial Waste

Moreover, the chance for pollution from industrial and medical hazardous waste seems high. While households are a minor source of this problem, the report says it is a serious potential one from industrial and port facilities.

The report notes that most of the industrial hazardous waste is produced by the petrochemical and pharmaceutical factories in Abidjan; small quantities are also produced by laboratories. The mining industry, concentrated in the centre and north of the country, generates significant quantities of such waste, notably from the use of mercury in gold mines. Presumably, these could find their way into inland streams and rivers that eventually end up in the Ébrié Lagoon. Car repair workshops are often close to the lagoon or an estuary and discharge waste directly into these waters.

Citing an environmental profile report in 2006 which referred to an investigation by the Office of Scientific and Technical Research Overseas (ORSTOM), and its successor the Institute for Research into Development in 1983, UNEP says an estimated 4.4 million cubic metres of liquid industrial waste was discharged into the lagoon in just one year.

“This amount has probably increased in the last few years, but no reliable data are available,” the UNEP report says.

However, it adds that “the most significant quantity” of wastewater comes from textile factories and tanneries, and from cleaning tanks used in the chemical industry. Other hazards lie elsewhere. Côte d’Ivoire’s international ports of Abidjan and San Pedro do not have facilities to treat hazardous waste. Presumably this task would be done by private companies. However, the UNEP report notes that “no procedure prevents collection companies to handle such wastes in addition to waste raised on conventional ships.” In the absence of proper monitoring of collection companies, it is conceivable, then, that some of such waste could filter into the lagoon, as would be the case of Abidjan Port or the Gulf of Guinea, in the case of San Pedro’s.

Similar deficiencies apply to hospital waste. A centralized waste management plan was suspended because of the civil war, but the current government has started updating the plan which is now being implemented.

Worst Affected Part of Lagoon

The Ébrié Lagoon runs east-west for about 150 kilometres covering a surface area of some 550 square kilometres. There is an additional 200 square kilometres of adjacent mangrove swamps and wetland. Ébrié forms part of an unbroken three-lagoon complex that includes the Aby and Grand Lahou. The Ébrié Lagoon, the largest of the three, is separated from the Gulf of Guinea by a narrow sandbar for almost its entire length. It is fed by fresh water from small creeks and rivers, notably the Comoé and Mé rivers at the east of the lagoon, and the Agnéby and Ira in the centre. The lagoon connects to the Gulf of Guinea via the man-made Vridi Canal, providing a gateway for shipping.

Pollution in the Ébrié Lagoon lessens as one travels eastward. At the extreme the water is entirely fresh due to intake from the Comoé. In the centre, at the Vridi Canal in Abidjan, clean seawater flushes the lagoon, since average depth of the lagoon is just 5 metres. This means there is no stagnant pool of water for long periods.

Mercury and other chemicals have been detected in the lagoon. High concentrations of mercury have been found in Barracuda, and very high ones in snapper and catfish, both very popular in the local diet. Accumulation of mercury in the food chain can affect the nervous system. So, people (especially children) who eat such contaminated fish risk storing this in their system. The result can be a breakdown in the nervous system. Côte d’Ivoire does not have legislation or national standards on mercury and consumption, so it cannot provide public food advisories on the matter.

Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, or DDT, banned in most countries some 40 years ago is present in the lagoon. The pesticide lasts very long in the environment and can accumulate in human fatty tissue. Analysis of lagoon fish and oysters shows the presence of detectable levels of DDT and its metabolites Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethane (DDD) and Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethylene (DDE), according to the report. While the concentrations are not alarmingly high, it says, “the sources of DDT in the lagoon should be established, and a wider study is recommended in order to assess levels of DDT in important food items, predatory fish, and human blood.”

Dieldrin is used against insects attacking cotton, corn, and citrus crops. The insecticide is also used to control locusts, mosquitoes, and termites; and is a wood preservative. However, the report notes Dieldrin was banned in the 1980s in North America and Europe due to its harmful effects on fish and wildlife. In humans, it decreases effectiveness of the immune system. It is carcinogenic and can harm reproduction and kidneys. People ingest Dieldrin by eating contaminated fish and shellfish. The UNEP report says, “The fact that levels above the detection limit were found in the lagoon may indicate that the substance is still in use in the country.”

Hydrocarbon pollutants are in the lagoon; the highest concentrations are nearest the drum-cleaning units of installations. This and other contaminants settle in the lagoon’s sediment. Plastics, which are not biodegradable, also litter parts of the lagoon in the Abidjan area, especially where tidal waves are weak.

The UNEP report suggests that more samples need to be analyzed in order to delineate the extent of the contamination. Then, a risk assessment is needed to ascertain the degree to which the heavy metals present a danger to public health, and then to assess whether there are measures needed to protect the public, such as banning the consumption of fish from that area. Moreover, the report says, a projected comparison would need to be made between the environmental consequences of cleaning up the contamination and disturbing the sediments or allowing nature to solve the problem. In cases of acute pollution, countries increasingly choose to dredge the sediment and treat it at site in a controlled environment, rather than to leave it nature.

In the case of Ébrié Lagoon, however, the reports says that layers of could simply be trawled and removed along with severely contaminated sediments.

Recovery Possible

The UNEP reports suggest that recovery of the lagoon is possible, and that this would make it potentially an engine of growth for Abidjan. For example, just 10 per cent of the lagoon is subject to pollution from extensive human activity. Recovery could occur, the report says, if the government removes the accumulated pollution, prevents further encroachment on the lagoon, and stops the use of the lagoon as a dump for solid and liquid waste. This, the report adds, would improve the lives of Abidjannais (the city’s residents), provide opportunities for artisanal fishermen, recreation, fast and efficient water transport, sport, and tourism with an attractive waterfront. Morocco has embarked on providing some of these facilities on the lagoon.

There is great tourism and leisure development potential around the lagoon.

However, the UNEP report suggests this transformation could only occur if management of the lagoon undertaken with coordinated policy initiatives. The other key element is to institute long-term, coordinated and substantial effort, a job that should go to an Ébrié Lagoon Authority.

Recommendations

To avoid duplication, the UNEP report recommends that waste collection be improved by connecting all parts of the city, regardless of their legal states, to a network. Additionally, the government should create the regulatory framework for the establishment of private hazardous waste infrastructure. This is because there appears to be demand for such services, which could generate profit.

The sewerage collection network needs expansion, and booster pumps should be connected to it in old and new areas of the city. The UNEP report also calls for redesign, upgrade and reactivation of the sewerage treatment plants. Currently, sewerage is poorly treated before discharge in the lagoon.

Naturally, all these measures require “significant resources from the city” which would have to come from taxes. If not, the UNEP report suggests, services would deteriorate, and the quality of life for residents would be eroded. The report notes that communities are often willing to pay for such services so long as they are efficient. Therefore, it is vital to find capital to establish the system, backed with adequate policies to recover investment. The UNEP report thus suggests that the private sector could be involved in building urban environmental infrastructure, so long as companies get a return on their investments.

Photo Credit: UNEP Geneva.

The fortunes of the lagoon and city are inextricably linked.

During the “Ivorian [economic] miracle” – from the 1960s though 1980s – a Ministry of Maritime Affairs also took charge of the lagoon, and there was no pollution. The lagoon’s fortunes and those of the city appear to be inextricably linked. Today, Abidjan is on a resurgence toward its golden age. The lagoon’s recovery would constitute a giant effort in the realization of that objective.

2015-09-28 105635

2015-09-28 105704

2015-09-28 105725

2015-09-28 105739